Category blog

The daffodils are out. The cherry blossoms are in bloom. England’s famous meadows are looking their absolute best. And the headlines are all diabolical. It’s spring in the UK and the papers scream “Death of democracy”, “Cabinet in crisis”. Day… Continue Reading →

The library at Burnham Beeches, a decaying mansion in the Dandenong Ranges east of Melbourne, looks nothing like it did in its hay day in the 1930s. Now it sits inside a glass case flooded with inky water. Melbourne artist,… Continue Reading →

Thomas Kuegler is just having way too much fun. All the while attracting millions of followers and fulfilling a Millennial’s ultimate dream — to make a living out of social media. Tom, 25, has become famous largely by simply being himself, infectiously… Continue Reading →

The final nominees for this year’s World Press Photo Awards have just been announced. They are the amongst the best news photographers on the planet. This year, the contest saw 4,738 photographers from 129 countries enter 78,801 images The 2019… Continue Reading →

When Dads On The Air, now the world’s longest running fathers’ show, began in 2000 we had no idea we were part of a worldwide trend protesting the treatment of fathers in separated families. We were a small group of… Continue Reading →

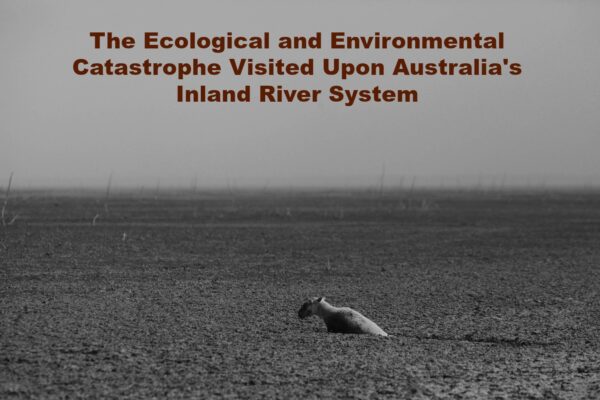

They blame climate change. They blame the drought. They blame everyone and everything but themselves. The stench of millions of dead fish, the rotting corpses of kangaroos and sheep, the missing bird life, the farmers who can no longer farm,… Continue Reading →

Lu Guang picked up a camera for the first time in 1980, still a teenager. He was a factory worker in his hometown of Yongkang in China’s Zhejiang Province. After studying in Beijing he became a freelance photographer in 1993,… Continue Reading →

At 89, former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke has declared himself in miserable health and unlikely to last much longer. While he expects the Labor Party, which he led for many years, to win the next election, due by May… Continue Reading →

By John Stapleton So it is done. The Coalition government has admitted defeat. Current Prime Minister Scott Morrison is not there to save the furniture. He’s there to steer his party to electoral oblivion. The ineptitude of the recent Wentworth… Continue Reading →

Let’s face it: this is a tough sell. In the beginning was the Word. Well, there was a radio show called Dads On The Air. We were a small group of that most unfashionable of all people. Separated, sad, angry, overwhelmed… Continue Reading →

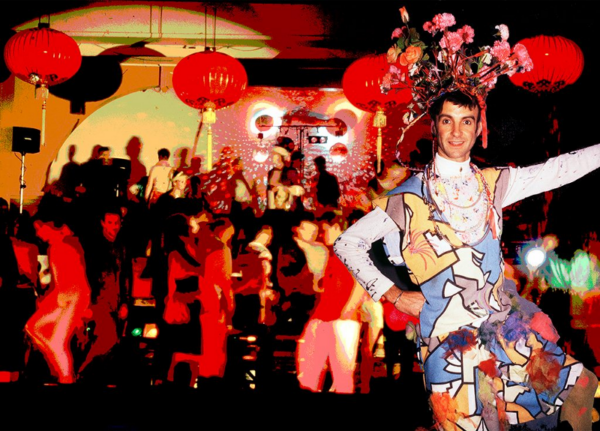

Farewell Old Friend Jac Vidgen became both famous and infamous for one thing: his parties. They grew from his lounge rooms in Elizabeth Bay in central Sydney in the 1970s, where I was a frequent visitor, to become truly massive… Continue Reading →

By John Stapleton The Demise of Malcolm Turnbull I am a vengeful god. The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; the Lord takes vengeance and is filled with wrath. The Lord takes vengeance on his foes and vents his wrath… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull Those Whom the Gods Would Destroy The Coverage Malcolm Turnbull’s Day of Reckoning has arrived. He could have left with dignity ten days ago; doctors advice, spend more time with his grandchildren. But this hapless… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull Let Slip the Dogs of War: Coverage The word “crisis” is bandied about a lot in discussing Australian politics right this minute. Nothing the present batch of oligarchs could do to manipulate, suppress or control… Continue Reading →

America’s Wars, Australia’s hypocrisy With his fate set and Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership in its death throes, it is time to look back across the wasteland of his leadership. The ritual lies of political combat: The Prime Minister has my… Continue Reading →

Australia’s Failing Democracy The Foundation Lie The frenetic efforts of a failing Prime Minister have curled into a frustrated ball of fury. And arguably the worst government in Australian history faces electoral wipeout. The slow motion trainwreck of Malcolm Turnbull’s… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull The First Harpoon Strikes the Flank In the petri dish of Australian politics, the Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull thrashes in a blood soaked sea. The first leadership spill, on Tuesday 21st August, 2018, precipitated by the… Continue Reading →

Future Crimes is the Must Read Book of the Year. Endlessly fascinating, genuinely instructive, and truly frightening. One of the world’s leading authorities on global security, Marc Goodman takes readers deep into the digital underground to expose the alarming ways criminals, corporations, and even countries are using new and emerging technologies against you-and how this makes everyone more vulnerable than ever imagined. Goodman spent a career in law enforcement, including work as Futurist with the FBI and a Senior Advisor to Interpol.

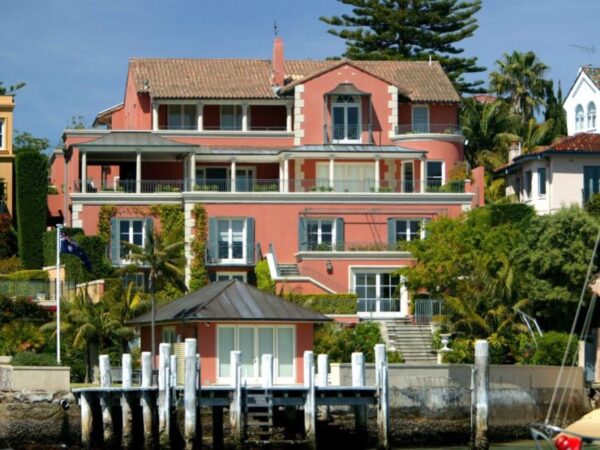

A House of Cards Collapses “Mr Harbourside Mansion” was a pejorative term coined by critics within Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s own party. The insult stuck. Indeed it is Turnbull’s often boasted about wealth which has been his undoing. A… Continue Reading →

The Fight Is On At the centre of the maelstrom which has overtaken Australian politics this weekend lies one man: the departing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. Disliked by the public, disliked by his own party, disliked by the public service, Australia’s… Continue Reading →

The leadership is in play. Diabolical polling ensures that. But how Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership devolved to the current disaster is a complicated yarn, like the man himself. So let’s begin at the beginning. Rob Hirst, drummer for Midnight Oil,… Continue Reading →

The Places in Between by Scottish author Rory Stewart is one of the most beautiful travel books ever written. He walked across Afghanistan-surviving by his wits, his knowledge of Persian dialects and Muslim customs, and the kindness of strangers. By day he passed through mountains covered in nine feet of snow, hamlets burned and emptied by the Taliban, and communities thriving amid the remains of medieval civilizations. By night he slept on villagers’ floors, shared their meals, and listened to their stories of the recent and ancient past. Along the way Stewart met heroes and rogues, tribal elders and teenage soldiers, Taliban commanders and foreign-aid workers. He was also adopted by an unexpected companion-a retired fighting mastiff he named Babur in honor of Afghanistan’s first Mughal emperor, in whose footsteps the pair was following.

Surveillance in Australia Australia has a government run on announceables. Even without the Budget blizzard, so far in 2018 we have had major announcements on everything from the so-called Gonski 2.0 education reforms, the establishment of an Australian arms industry… Continue Reading →

“Emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum wrote in her incisive treatise on the intelligence of emotions, titled after Proust’s powerful poetic image depicting the emotions as “geologic upheavals of thought.” But much of the messiness of our emotions comes from the inverse: Our thoughts, in a sense, are geologic upheavals of feeling — an immensity of our reasoning is devoted to making sense of, or rationalizing, the emotional patterns that underpin our intuitive responses to the world and therefore shape our very reality. Our interior lives unfold across landscapes that seem to belong to an alien world whose terrain is as difficult to map as it is to navigate — a world against which the young Dostoyevsky roiled in a frustrated letter on reason and emotion, and one which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry embraced so lyrically in one of the most memorable lines from The Little Prince: “It is such a secret place, the land of tears.”

The Abbott and Turnbull governments have mounted the greatest attack on freedom of speech in Australian history. Legislation being pushed through by the Australian government earlier this year under the guise of national security, allowing for journalists and whistle-blowers to… Continue Reading →

Today, every Australian child is at risk of being deprived of the protection of their biological family, because we have collectively failed to recognise the supreme guardianship powers of the State. Perceived legal rights to the protection of their own family, something everybody assumes parents and children are entitled to, are in fact non-existent. This has resulted in the creation of a multi-billion-dollar child-removal industry, engaged in the redistribution of stolen children for profit, across the Western world.

The world is turning into one vast Disneyland. Authentic travel experiences are becoming increasingly hard to come across. “Let’s go blah blah blah the tourists”, is the cry of touts from once isolated mountain kingdoms to once scarcely visited tropical islands. Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism by journalist Elizabeth Becker is the most significant book to be written on the industry this decade. Tourism, fast becoming the largest global business, employing one out of twelve persons and produces $6.5 trillion of the world’s economy. Tourism is the top single revenue source in countries as diverse as France and Thailand.

“I struggle awake and there she is, Russia. A silver-haired grandmother in a flowered nightgown.” After two and a half years as Moscow bureau chief for National Public Radio and co-host of the Morning Edition, America’s most widely heard radio news program, author David Greene journeys thousands of kilometres by rail from Moscow to the Pacific port of Vladivostok to find out how Russians’ lives have changed in the post-Soviet years. He meets a group of singing babushkas from Buranovo, a teenager hawking ‘space rocks’ from a meteor shower in Chelyabinsk, and activists battling for environmental regulation in the pollution-choked town of Baikalsk.

Highly controversial, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia has a troubled history. Leading Australian publisher Allen & Unwin ditched the book in November, 2017, citing fear of legal action from the Chinese government or its proxies. The book was originally subtitled: How China Is Turning Australia into a Puppet State.

Speaking to The Sydney Morning Herald, author Clive Hamilton said: “I’m not aware of any other instance in Australian history where a foreign power has stopped publication of a book that criticises it. The reason they’ve decided not to publish this book is the very reason the book needs to be published.”

The book was only published after it was tendered as part of an Australian government inquiry into foreign interference. The SMH recorded: While such activity is carried out by other states, elements of Beijing’s influence campaign are clandestine or highly opaque. According to media investigations and warnings from spy agency ASIO, these efforts are targeted at Australian politicians and academics.

Abe Books has picked their Top 50 Travel Books of all time.

And here’s a pick of ten of our favourites: