Author aSense

By John Stapleton The Demise of Malcolm Turnbull I am a vengeful god. The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; the Lord takes vengeance and is filled with wrath. The Lord takes vengeance on his foes and vents his wrath… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull Those Whom the Gods Would Destroy The Coverage Malcolm Turnbull’s Day of Reckoning has arrived. He could have left with dignity ten days ago; doctors advice, spend more time with his grandchildren. But this hapless… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull Let Slip the Dogs of War: Coverage The word “crisis” is bandied about a lot in discussing Australian politics right this minute. Nothing the present batch of oligarchs could do to manipulate, suppress or control… Continue Reading →

America’s Wars, Australia’s hypocrisy With his fate set and Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership in its death throes, it is time to look back across the wasteland of his leadership. The ritual lies of political combat: The Prime Minister has my… Continue Reading →

Australia’s Failing Democracy The Foundation Lie The frenetic efforts of a failing Prime Minister have curled into a frustrated ball of fury. And arguably the worst government in Australian history faces electoral wipeout. The slow motion trainwreck of Malcolm Turnbull’s… Continue Reading →

The Terrible Legacy of Malcolm Turnbull The First Harpoon Strikes the Flank In the petri dish of Australian politics, the Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull thrashes in a blood soaked sea. The first leadership spill, on Tuesday 21st August, 2018, precipitated by the… Continue Reading →

Future Crimes is the Must Read Book of the Year. Endlessly fascinating, genuinely instructive, and truly frightening. One of the world’s leading authorities on global security, Marc Goodman takes readers deep into the digital underground to expose the alarming ways criminals, corporations, and even countries are using new and emerging technologies against you-and how this makes everyone more vulnerable than ever imagined. Goodman spent a career in law enforcement, including work as Futurist with the FBI and a Senior Advisor to Interpol.

A House of Cards Collapses “Mr Harbourside Mansion” was a pejorative term coined by critics within Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s own party. The insult stuck. Indeed it is Turnbull’s often boasted about wealth which has been his undoing. A… Continue Reading →

The Fight Is On At the centre of the maelstrom which has overtaken Australian politics this weekend lies one man: the departing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. Disliked by the public, disliked by his own party, disliked by the public service, Australia’s… Continue Reading →

The leadership is in play. Diabolical polling ensures that. But how Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership devolved to the current disaster is a complicated yarn, like the man himself. So let’s begin at the beginning. Rob Hirst, drummer for Midnight Oil,… Continue Reading →

The Places in Between by Scottish author Rory Stewart is one of the most beautiful travel books ever written. He walked across Afghanistan-surviving by his wits, his knowledge of Persian dialects and Muslim customs, and the kindness of strangers. By day he passed through mountains covered in nine feet of snow, hamlets burned and emptied by the Taliban, and communities thriving amid the remains of medieval civilizations. By night he slept on villagers’ floors, shared their meals, and listened to their stories of the recent and ancient past. Along the way Stewart met heroes and rogues, tribal elders and teenage soldiers, Taliban commanders and foreign-aid workers. He was also adopted by an unexpected companion-a retired fighting mastiff he named Babur in honor of Afghanistan’s first Mughal emperor, in whose footsteps the pair was following.

Surveillance in Australia Australia has a government run on announceables. Even without the Budget blizzard, so far in 2018 we have had major announcements on everything from the so-called Gonski 2.0 education reforms, the establishment of an Australian arms industry… Continue Reading →

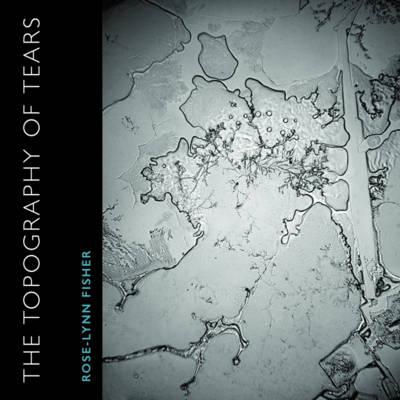

“Emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum wrote in her incisive treatise on the intelligence of emotions, titled after Proust’s powerful poetic image depicting the emotions as “geologic upheavals of thought.” But much of the messiness of our emotions comes from the inverse: Our thoughts, in a sense, are geologic upheavals of feeling — an immensity of our reasoning is devoted to making sense of, or rationalizing, the emotional patterns that underpin our intuitive responses to the world and therefore shape our very reality. Our interior lives unfold across landscapes that seem to belong to an alien world whose terrain is as difficult to map as it is to navigate — a world against which the young Dostoyevsky roiled in a frustrated letter on reason and emotion, and one which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry embraced so lyrically in one of the most memorable lines from The Little Prince: “It is such a secret place, the land of tears.”

The Abbott and Turnbull governments have mounted the greatest attack on freedom of speech in Australian history. Legislation being pushed through by the Australian government earlier this year under the guise of national security, allowing for journalists and whistle-blowers to… Continue Reading →

Today, every Australian child is at risk of being deprived of the protection of their biological family, because we have collectively failed to recognise the supreme guardianship powers of the State. Perceived legal rights to the protection of their own family, something everybody assumes parents and children are entitled to, are in fact non-existent. This has resulted in the creation of a multi-billion-dollar child-removal industry, engaged in the redistribution of stolen children for profit, across the Western world.

The world is turning into one vast Disneyland. Authentic travel experiences are becoming increasingly hard to come across. “Let’s go blah blah blah the tourists”, is the cry of touts from once isolated mountain kingdoms to once scarcely visited tropical islands. Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism by journalist Elizabeth Becker is the most significant book to be written on the industry this decade. Tourism, fast becoming the largest global business, employing one out of twelve persons and produces $6.5 trillion of the world’s economy. Tourism is the top single revenue source in countries as diverse as France and Thailand.

“I struggle awake and there she is, Russia. A silver-haired grandmother in a flowered nightgown.” After two and a half years as Moscow bureau chief for National Public Radio and co-host of the Morning Edition, America’s most widely heard radio news program, author David Greene journeys thousands of kilometres by rail from Moscow to the Pacific port of Vladivostok to find out how Russians’ lives have changed in the post-Soviet years. He meets a group of singing babushkas from Buranovo, a teenager hawking ‘space rocks’ from a meteor shower in Chelyabinsk, and activists battling for environmental regulation in the pollution-choked town of Baikalsk.

Highly controversial, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia has a troubled history. Leading Australian publisher Allen & Unwin ditched the book in November, 2017, citing fear of legal action from the Chinese government or its proxies. The book was originally subtitled: How China Is Turning Australia into a Puppet State.

Speaking to The Sydney Morning Herald, author Clive Hamilton said: “I’m not aware of any other instance in Australian history where a foreign power has stopped publication of a book that criticises it. The reason they’ve decided not to publish this book is the very reason the book needs to be published.”

The book was only published after it was tendered as part of an Australian government inquiry into foreign interference. The SMH recorded: While such activity is carried out by other states, elements of Beijing’s influence campaign are clandestine or highly opaque. According to media investigations and warnings from spy agency ASIO, these efforts are targeted at Australian politicians and academics.

Abe Books has picked their Top 50 Travel Books of all time.

And here’s a pick of ten of our favourites:

Read More…

Hotel Kerobokan, or Hotel K, is Bali’s most notorious jail. With the murderous Widoto regime of Indonesian executing another group of foreigners for alleged trafficking, while the Indonesians who sold them the drugs are not so much as charged, the rank corruption of Indonesia’s notoriously dishonest justice system has been exposed for all to see. Widoto’s decision to ignore international outcry over the executions has plummeted his country’s reputation to new lows. Billions of dollars in foreign aid flow to Indonesia each to prop up this appalling regime. It is a clear abuse of international taxpayers resources and should be stopped. In Hotel K: The Shocking Inside Story of Bali’s Most Notorious Jail, acclaimed Australian journalist Kathryn Bonella exposes the inside of hell, Indonesia’s barbaric penal system.

ASIO: The Enemy Within, largely ignored by Australia’s mainstream media, is a must read book for anyone wanting to understand the conundrum that is Australia today. Critics describe the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation as a secret police force which has done enormous harm to the country’s once flourishing democracy. The country’s politicians have remained silent, either out of their own personal fears or because it suits them. This is an important book which is long overdue. With the Australian government gifting extraordinary powers, protecting it from journalistic scrutiny with some of the most totalitarian legislation imaginable, and increasing its funding in the order of hundreds of millions of dollars in the so-called war on terror, this book is more relevant than ever. Author of ASIO: The Enemy Within, Michael Tubbs, a barrister who took the fight to one of the countries most secretive organisations, is a credible and powerful critic, all the more so because he is not a professional writer but a concerned citizen who has seen at first hand, as a representative of aggrieved parties, too many lives and careers pointlessly destroyed. If you want to know what ASIO has been doing in and to Australian society, this is the book for you. Other books have been written about ASIO, but this book is unique in many ways. No one is better qualified to deal with Australia’s premier domestic nosey parker than Michael Tubbs, one of the few barristers who took the fight up to ASIO by appearing for clients who had fallen foul of its powers. No punches are pulled as Tubbs tries to deliver the Knock-out blow to ASIO and put it out of business. If you want to know how ASIO’s national network of political spies have surreptitiously and manipulatively affected Australia’s free society and changed its political landscape, you need to read this book.

Plunder and Deceit, Mark Levin’s latest offering, has debuted at Number One on the New York Times bestseller lists. Levin argues that in modern America, the civil society is being steadily devoured by a ubiquitous federal government. But as the government grows into an increasingly authoritarian and centralized federal Leviathan, many parents continue to tolerate, if not enthusiastically champion, grievous public policies that threaten their children and successive generations with a grim future at the hands of a brazenly expanding and imploding entitlement state poised to burden them with massive debt, mediocre education, waves of immigration, and a deteriorating national defense. The arguments in Plunder and Deceit can be extrapolated to every Western country.

From the highly acclaimed, multiple award-winning Anthony Doerr, the beautiful, stunningly ambitious instant bestseller about a blind French girl and a German boy whose paths collide in occupied France as both try to survive the devastation of World War II. All the Light We Cannot See has won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. The judging panel called Doerr’s book “an imaginative and intricate novel”, which is “written in short, elegant chapters that explore human nature and the contradictory power of technology”. The Guardian described it as “a piece of luck for anyone with a long plane journey or beach holiday ahead. It is such a page-turner, entirely absorbing.”

America’s Destruction of Iraq fills in the gaps of how America’s disastrous invasion of Iraq created the ultimate breeding ground for the Islamic State. Compounding in detail, compelling in outrage, here are some extracts.

Melbourne-born, Athens-based poet, author, publisher, designer, teacher and musician Jessica Bellreleases her insightful, incredibly candid memoir, Dear Reflection: I Never Meant To Be A Rebel.

The book is a firsthand recount of her turbulent youth and early adulthood as the child of Erika Bach and Demetri Vlass, founders of seminal Melburnian indie bands Ape The Cry and Hard Candy. Though loving, encouraging parents, Bach and Vlass battled their own demons over the years, the former managing a back problem that “became a nightmare of pill popping, alcohol abuse and anxiety attacks”, and the latter “retreating into silence for fear of triggering Erika’s drug-induced psychosis”.

Pre-orders are now available for Tim Winton’s Island Home: A Landscape Memoir, the latest from one of Australia’s most loved writers.

Winton writes: “I grew up on the world’s largest island. I’m increasingly mindful of the degree to which geography, distance and weather have moulded my sensory palate, my imagination and expectations. The island continent has not been mere background. Landscape has exerted a kind of force upon me that is every bit as geological as family.

“To be a writer preoccupied with landscape is to accept a weird and constant tension between the indoors and the outdoors. I am so thin-skinned about weather and so eager for physical sensation I seem to spend a shameful amount of energy fretting and plotting escape, like a schoolboy. Sat near a window as a pupil, I was a dead loss. And I’m not much different now. I can’t even hang a painting in my workroom, for what else is a painting but a window? My thoughts are drawn outward; I’m entranced. This country leans in on you. It weighs down hard. Like family. To my way of thinking, it is family.”

Extract from She Said She Said.

I talk about my impending trip to Australia to see my family. I mention that my sister is travelling at the same time. Paula walks past and says something to me. As she walks away, the mother asks, “So. Is that your sister?”

I blurt out, “Oh, no. That used to be my husband.”

Not my proudest moment. She is bewildered. I am appalled at what I said.

I want to hide under a rock somewhere.

Dirty Wars is story from the frontlines of the undeclared battlefields of the War on Terror. Award-winning journalist and best-selling author Jeremy Scahill documents the new paradigm of American war: fought far from any declared battlefield, by units that do not officially exist, in thousands of operations a month that are never publicly acknowledged. From Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen, Somalia and beyond, Scahill speaks to the CIA agents, mercenaries and elite Special Operations Forces operators who populate the dark side of the many wars America is fighting. He goes deep into al Qaeda held territory in Yemen and walks the streets of Mogadishu with CIA-backed warlords. We also meet the survivors of US night raids and drone strikes, including families of US citizens targeted for assassination by their own government -who reveal the human consequences of the dirty wars the United States struggles to keep hidden.

A Sense of Place Publishing is proud to announce the forthcoming publication of She Said She Said.

The ordinary and the extraordinary mix in this excruciatingly intimate, and at times triumphant and funny book which tells a profoundly moving story which could have been custom built for our times.

Anne M Reid had the perfect life with her perfect partner. She and Paul were together for 12 years, married with three beautiful children.

One night, without warning, Paul reveals that as a young child, he had wanted to be a girl. He had felt a total disconnection with his body and at one stage tried to castrate himself.

The book explores the nightmare Anne faced as Paul transitions to Paula, initially with hormonal treatment and eventually surgery. Anne’s husband not only had a new sex, but a new personality, different likes and dislikes, and a different take on the world. The husband she knew simply vanished and a stranger emerged.