By Michelle Fahy with Michael West Media

After 28 years with Defence Science and Technology, on Friday 28 October 2016 Dr Tony Lindsay, one of Australia’s most eminent defence scientists, said goodbye. The following Tuesday, 1 November, he started work with the world’s largest arms manufacturer, Lockheed Martin. Michelle Fahy reports on Australia’s revolving door between military and industry.

For the previous eight years Lindsay had been Chief of the National Security and Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Division at DST, reporting to the Chief Defence Scientist and through him to the Defence Secretary. There probably wasn’t a classified weapons-related research project in the country that Lindsay didn’t know about. Yet in the space of a few days he’d switched from public to private interests, moved to Melbourne, and become Director of the new STELaRLab, Lockheed’s first R&D lab outside the USA.

Tony Lindsay graduated in Science in 1983 with a double major in Physics and Mathematics from James Cook University. He did Honours in Physics and in 1989 was awarded a PhD for research in atomic spectroscopy. He joined DST in 1988 as a researcher in electronic warfare. He has worked closely with defence scientists in the UK and also the USA. For two years he held the diplomatic post of Counsellor, Defence Science at Australia’s embassy in Washington DC, after which he returned to Australia in 2008 to take up what became his final position at DST, as a Division Chief.

Global Giant Lockheed Martin

Globally, Lockheed Martin has annual sales around US$54 billion, 88 per cent of which come from the design and supply of modern warfighting equipment to the world’s militaries. Along with other military industry contractors, Lockheed Martin has been criticised in recent years for continuing to supply Saudi Arabia with weapons for the war in Yemen, a human rights catastrophe affecting millions.

In response to questions on Yemen, Lockheed CEO Marillyn Hewson stated, ”We continue to be aligned with the [US] administration’s policies, and we intend to honor our commitments…” as though allegiance to the flag absolves the corporation of ethical responsibility for its contribution to ongoing war crimes.

In Australia, Lockheed Martin is a multi-billion dollar contractor to the Defence Department ($5.4 billion in the five years to 30.6.19).

It is most well known here as the creator of the F-35, a combat aircraft that, depending on which side of the fence you sit, is either an advanced stealth fighter or a “little turd.”

Either way, the Australian government ordered 72 of them, for $17 billion. Lockheed is, however, involved in many more projects here than fighter jets.

The Defence Science and Technology Group has long been closely associated with industry through research collaborations. In late 2013 it ramped up its commitment to industry collaboration signing a number of agreements with large arms manufacturers. This included Lockheed Martin, with whom it signed a ten year partnership agreement in March 2014.

During the same period the Group also commenced a scheme of industry placements for DST staff. The logos of seven of the world’s top ten weapon-makers appear on DSTG’s website.

On top of Lindsay’s almost instant transfer from the public to private sector, the ten year partnership agreement between DST Group and his future employer adds further grounds for concern as to conflicts of interest. Several other factors listed in the APS Code of Conduct on conflict of interest are also likely to have applied in Lindsay’s case. (See box at end.)

On 2 August 2016, then Defence Minister Marise Payne announced Lindsay’s move:

Defence scientist appointed to lead Lockheed Martin’s new research facility

…Dr Lindsay has had a distinguished 28 year career with DST Group and will bring a wealth of knowledge and insight into his new role… His appointment is a testament to his leadership in his field and demonstrates the high regard in which DST Group is held within the defence industry…Dr Lindsay will finish with DST Group in October before beginning his role with Lockheed later in the year.

Whether Minister Payne was aware that the gap separating Dr Lindsay’s exit from DST and his commencement at Lockheed would be so short is unknown. As part of a broader Freedom of Information inquiry we requested relevant communications between DST and the Minister’s office. None were supplied.

Lindsay’s Lockheed move is a good example of how the revolving door between the public sector and military-related private industry in Australia is being facilitated by both sides.

Of perpetual concern is the general lack of transparency, usually for ‘national security’ reasons, that accompanies Defence activities.

When combined with ‘commercial in confidence’ restrictions providing cover for private interests, few details reach the public, hampering scrutiny of what may be serious conflicts of interest.Brothers-in-Arms: the high-rotation revolving door between the Australian government and arms…

The majority of transitions between politics and the Australian defence sector pass unremarked, with only an occasional…www.michaelwest.com.au

Many details provided here emerged only as a result of our FOI inquiry, even so, much relevant information was either never documented, withheld, or redacted.

Interestingly, the CEO of Lockheed Martin Australia at the time of Lindsay’s appointment was another revolving door beneficiary. Rear Admiral Raydon Gates followed a long career in the navy with a second career in industry, including time as Lockheed’s Australian CEO from 2011–2017.

Failure to follow required notification procedures

At the time Lindsay resigned there were defence instructions for those employees considering a move such as his, where there was “a possibility, or any potential for a perception, of a conflict of interest.” A letter of notification was required outlining “any relationship that exists between their official duties during the previous two years and the proposed employment.”

This requirement was “most pertinent to Defence personnel who are in senior positions.” As to timing, “no later than the short-list stage, or in cases of an unsolicited offer, immediately upon receipt of that offer.” In all cases, the letter was required prior to accepting a job offer.

The documents released under FOI contain no mention of a notification letter being supplied by Lindsay.

In an email dated 16 September 2016 — more than two months after Lindsay and his boss knew he was leaving for Lockheed, and six weeks after the minister’s media release — Defence’s Directorate of Senior Officer Management provided Lindsay with a copy of the defence instructions “for your information and action as necessary.” If there was any response by Lindsay, it was not released to us.

The defence instructions direct that any conflicts of interest are to be managed by the person’s supervisor. They list measures that may be used such as allocating alternate duties, restricting the flow of information to the employee, and/or restricting their access to information. From the documents supplied, it does not appear that Chief Defence Scientist Dr Alex Zelinsky undertook such measures in Lindsay’s case.

The instructions also say a statutory declaration may be requested by the Secretary to confirm the employee’s understanding of their post-separation legal obligations as to confidentiality and non-disclosure. None of the documents indicate Lindsay was asked to provide a statutory declaration.

When did Lindsay first advise Zelinsky of the possibility of his move to Lockheed?

We don’t know. The earliest document released is an email dated 7 July 2016 which indicates that Lindsay and Zelinsky (and Lockheed) had already reached agreement on his move and were by then discussing any ‘post-separation restrictions’ that would be imposed on him after he joined Lockheed (of which there would be only one, it seems, due to a ‘perceived’ conflict of interest on a RAAF-related project).

So, sixteen weeks before he eventually left, it was known by his boss he’d be going, yet Lindsay was apparently proceeding as normal in his role.

On 25 July 2016, Lindsay’s resignation was “still being kept very quiet,” but it had been “discussed at the Secretary’s roundtable” that morning, according to internal emails.

How did Defence manage its own ‘pre-separation’ conflicts of interest?

No plan or details of formal direction on this topic were included in the documents released. An ‘exit strategy’ for Lindsay is referred to in some documents as having been negotiated by Zelinsky with Lockheed Martin, a process required by defence instructions, but the strategy itself was not released (even in redacted form). Conversely, there was an activity added to Lindsay’s calendar under the exit strategy which increased conflict of interest concerns — a US trip — covered later.

The documents released suggest there was no significant adjustment made to Lindsay’s role or activities to mitigate conflicts of interest. There is a possibility some change may have occurred from 22 August but this requires clarification, as follows.Bow Your Heads In Shame: Arm Merchants and the Australian Government

By Michelle Fahy with Michael West Mediamedium.com

Six days after Marise Payne’s media release, 8 August 2016, Zelinsky announced Lindsay’s resignation to all DST staff. He said Lindsay would continue as Chief of the National Security and Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Division until he left at the end of October. There is no mention of any changes or restrictions in Lindsay’s normal lines of communication. See figure 1.

Two days later, in an email to Lindsay, Zelinsky reminds him of an agreement to appoint an acting chief of Division from 22 August–30 November (unmentioned in the 8 August all-staff email). An internal recruitment process for an acting chief started on 11 August. No details have been provided explaining how the acting chief fit in with Lindsay’s ongoing presence and activities. The acting chief is not mentioned again in the documents.

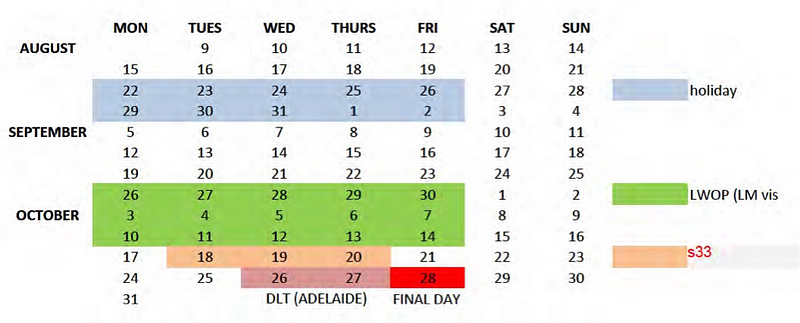

On 12 August, Lindsay emailed relevant staffers his “broad exit plan,” covering his final two and a half months with DST. See figure 2. Again, there’s no indication of any communication or access restrictions. Further, he says he’ll be “back on deck” with DST after his three week US trip. In a letter to Lockheed Martin on 7 September 2016 he signs off as “Chief, National Security & Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance Division” and, in subsequent emails and documents he is still referred to as Chief, and he refers to himself as Chief on his emails. Finally, he still attended the October DST Leadership meeting.

Thus, there’s no evidence in the documents the acting chief fully replaced Lindsay as Chief from 22 August, indeed there’s evidence to the contrary, but there is a possibility it was so. Regardless, at the least, Lindsay continued working to wrap up his DST Group activities, and attended a 3-day classified event plus the October DST Leadership meeting.

Figure 1: Excerpt from Dr Zelinsky’s eNews to staff, 8 August 2016

Figure 2: Email and calendar from Tony Lindsay to relevant DST staff with exit timetable, 12.8.16

Legend: CDS=Chief Defence Scientist; LWOP LM=Leave without pay, Lockheed Martin visit; s33=event name redacted on national security grounds; DLT (Adelaide)=DST Leadership Team meeting

But…. three weeks in the USA as a guest of Lockheed Martin?

Email: 19 August 2016

Good morning Dr Zelinsky

Lockheed Martin would like to extend an offer of hospitality to Dr Lindsay’s [sic] and invite him to the US in September.

To extend a formal invitation, LM are requesting DST Group’s acceptance of the payment as ‘Hospitality’ along with a note stating Dr Lindsay has been authorized unpaid leave of absence to travel in support of Lockheed Martin’s efforts.

I have attached the ‘Hospitality Letter’ that outlines the value and purpose of each payment…

The above is from an email sent by Lockheed Martin Australia’s ‘Talent Acquisition Lead’ to Alex Zelinsky, making arrangements for Lindsay to travel to the US for a three week orientation in preparation for his new role at Lockheed Martin. After the trip, Lindsay returned to DST.

See the schedule of ‘hospitality’ payments in figure 3. The amounts paid have been redacted on s47 grounds (trade secrets and commercially valuable information). Most items are unremarkable, even the welcome gift, depending on its value, but what is the ‘Lockheed Martin Training Fee’? No explanation of this item appears in the documentation we have seen.

The larger question, however, is whether this US trip should have been permitted at all (regardless of it being unpaid leave) during Lindsay’s continuing tenure with DST and given the inherent conflict of interest created by his senior position at DST while Lockheed was both a formal DST partner and a major defence contractor… and now also his future employer.

Despite these significant conflicts, Lindsay himself, along with several defence authorities, including Human Resources, the Chief Defence Scientist, and Defence’s CFO Group had no issue with him going. To all of them, the fact he would be on leave without pay dissolved any concerns (as though he turned his brain off along with his salary). Defence CFO Group noted its further grounds for approval that, “as stated on the DST Group website, this employment opportunity is in Defence’s interest.” Lindsay confirmed in a letter to Lockheed on 7 September 2016 that, “The DST Group fully supports this trip.”

It goes without saying that Lindsay ought not have been paid by the Commonwealth while on this trip, but his salary is surely not the only consideration. The fact that none of these influential areas within Defence appeared to consider the other obvious conflicts created by this proposal does not inspire confidence that the substantive underlying conflicts generated by DST’s close working relationships with industry were (are?) being recognised, assessed and managed.

Figure 3: “Financial disclosure of the complete cost of the hospitality” emailed by Lockheed Martin to Dr Zelinsky for approval, 19 August 2016 (and subsequently signed off by Zelinsky)

Time for a rethink?

The Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office raises an interesting topic in its guidelines on conflicts of interest — the issue of bias. The Ombudsman says, “[An] instance of bias might arise where, say, an officer is known to hold views on a particular subject that could suggest he or she might not bring an open mind to the subject.”

Considering the Lindsay case study of (apparently) unacknowledged and unmanaged conflicted interests, might there be a lack of impartiality, indeed an outright bias, towards facilitating industry interests in tandem with defence interests? Perhaps even a conflation of the two? Could this explain how the manner and timing of Lindsay’s move to Lockheed was seen by apparently all involved, right up to ministerial level, as being of no serious concern and, in fact, as an overall positive, thus requiring no close management and no apparent restrictive measures?

The Commonwealth Ombudsman’s guidelines for managing conflicts of interest use stronger language than that employed by Defence. Might such wording be considered as a new starting point by Defence? [emphasis added]:

While avoiding conflicts is generally preferable, in practice there may be some situations in which conflicts of interest cannot be wholly avoided and need to be managed in a way which will withstand external scrutiny.

The phrase “withstand external scrutiny” is bracing, the implication clear. Had such a litmus test been applied to Tony Lindsay’s unfettered transfer to Lockheed Martin it is difficult to see how even one of the following things would have occurred, let alone all three:

- He remained a participant in the senior leadership team at DST Group from the day he notified his intention to resign until the day he left, almost four months later, despite DST Group’s close and ongoing contractual agreements with his future employer.

- After tendering his resignation, while still in the employ of the Commonwealth, he undertook a three week unpaid leave of absence and travelled to the USA, at his future employer’s expense, for the purpose of his orientation in preparation for his future employment with Lockheed, after which he returned to his paid senior role at DST for a further two weeks.

- Upon leaving DST, with a three day weekend the only gap in time, he commenced his new senior leadership role with Lockheed Martin Australia, in a related field, with LM continuing in close partnership with DST Group while also remaining a significant contractor to Defence more broadly.

It is remarkable that this series of occurrences, all waved through by Defence, should even need to be listed as being inappropriate for one of Australia’s most senior defence science officials in an extraordinarily sensitive national security-related role.

Why the concern with staff movement between public and private sectors in a related field?

The Australian Public Service (APS) Code of Conduct says there are three key risks when public employees accept employment in related private fields: 1) they’ll use their APS position to favour their new employer, 2) they’ll reveal confidential or sensitive information to that employer or provide other information that gives that employer an advantage in dealing with government or in the market generally, 3) they’ll use inside knowledge and contacts to benefit the new employer in influencing government.

The Code provides examples, some of which are listed below.

Public employees intent on accepting a related private sector role could be involved in a conflict of interest if their APS work involves:

- anticipated or actual contractual or funding relationships between the Commonwealth and the proposed employer

- the exercise of discretion in conferring some advantage on the proposed employer…

- knowledge of confidential procedures and criteria used within an agency which could allow anticipation or manipulation of agency decisions

- knowledge of government intentions that could confer direct financial advantage on those able to participate.

The Code also states that a private sector appointment can raise an immediate real or apparent conflict if it’s with an organisation that is “in a special or close working relationship” with the APS employee’s agency.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michelle Fahy

Contributing Editor — Michael West Media’s Revolving Doors. Michelle has had a long career in writing and research, initially in the financial services sector producing plain language investor communications. For the last 10 years, she has been involved in research and campaigning for various organisations seeking to reduce warfare and militarism. An abiding interest has been the prevention of corruption via increased transparency and accountability.

Fahy is currently researching the links between current and former politicians, public servants and military personnel, and weapons-making corporations.

This story was originally published in Australia’s leading investigative news site Michael West Media and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence and with their kind cooperation.

FEATURED BOOKS

2 Pingbacks