By Professor Ramesh Thakur

If ever there was justification for a Royal Commission, this is it. Its primary term of reference should not be to apportion blame, but to identify how we can prepare better for the next big one.

With 102 deaths as of 10 June, COVID-19 does not make it to the top 50 causes of deaths in Australia, coming behind poisoning with 110 deaths. And for that we have inflicted such damage on people’s lives, livelihoods, education, and freedoms, condemning them to house arrests en masse and robbing so many young people of their future?

As Walter Scheidel reminds us in an essay in Foreign Affairs, SARS-CoV-2 has not been even remotely as lethal as the Spanish flu of 1918–19 that killed the fit and young as virulently as it did the elderly and infirm. It infected 500 million people (one-third the world’s population at the time) and killed around 50 million. Scaled up to the current global population, that would translate to around 200-250 million dead today. In other deadly pandemic episodes since then, we suffered but endured.

The global death toll from COVID-19 was just over 411,000 on 10 June. Our health systems are infinitely better than they were a century ago. Yet authorities did not close down whole societies and economies in 1918. The state did not enter into our homes to tell us how to live, who and how many we can meet, when, where, and what we can shop for, and what businesses can operate and under what conditions. COVID-19 too shall pass.

SARS-CoV-2 will not be the last pandemic to hit us. There will be others, and next time Australia may not be fortunate in the timing (off flu season) or the geographical epicentre (North Atlantic). The choice of Commissioners should reflect modern Australian demographics and the reality that the best lessons to be learnt for successful responses are from East Asian countries.

The inquiry should focus on two broad areas: the relationship between science, modelling, and evidence that informed policy; and the lives saved by the strategies adopted against the lives lost and livelihoods destroyed by the lockdown measures.

Science, Modelling, and Evidence behind Coronavirus Policy

Epidemiological modellers have not fared well in this crisis. Prior to this, the official position of the World Health Organisation (WHO) on the value of social distancing measures was published in an 85-page report last October. Its purported goal was to provide recommendations:

… for the use of NPIs [non-pharmaceutical interventions] in future influenza epidemics and pandemics based on existing guidance documents and the latest scientific literature. The specific recommendations are based on a systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of NPIs, including personal protective measures, environmental measures, social distancing measures and travel-related measures.

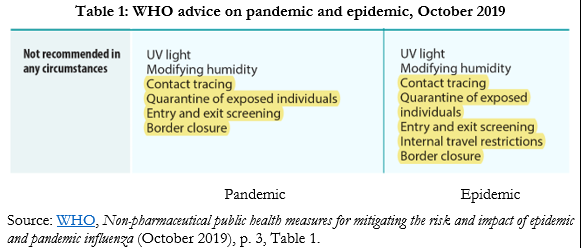

Table 1 is a screen grab of the summary advice that border screenings and closures, internal travel restrictions, quarantine of exposed individuals, and contact tracing are not recommended in any circumstances. There were two reasons for the WHO’s sceptical conclusion on these measures. For one, “sufficient evidence” exists to show ineffectiveness of entry and exit screening; “weak evidence” that travel restrictions may delay the introduction of infections only temporarily and can adversely affect mitigation programs and disrupt supply chains, and border closures may work for small island nations in severe cases, “but must be weighed against potentially serious economic consequences.”

For another, “social distancing measures… can be highly disruptive, and the cost of these measures must be weighed against their potential impact.”

Yet one after another, based on epidemiological modelling, governments introduced all these measures in a cascading rush. The pandemic was caused by a novel coronavirus.

The public health community had little reliable existing knowledge and no time to have come to clear conclusions on the science behind its emergence, growth, curve, and retreat, let alone the best mitigation and suppression measures to fight it. Accordingly, either the WHO guidance was not based in science and the epidemiologists have access to better scientific knowledge, in which case the public needs to know the basis of their confidence over that of the existing WHO advice, or else the existing science behind the October 2019 advice was sound, in which case the closures privileged abstract mathematical modelling over actual science based on observational data and medical scholarship.

If so, the peoples of the world have been subjected to an unethical experiment in contravention of the science.

Consider what in itself is a trivial but nonetheless telling example. Official advice from different authorities on the recommended social distancing measure ranges from 1 metre, to 1.5 (Australia) and 2 metres (UK, USA). Which one of the three is based on science? They can’t all be the scientific recommendation.

As with many other elements of official advice, the choice has real-world consequences. In the case of the UK’s absurd two-metre rule, Toby Young points out: “For most shops, the only way to keep customers six feet apart will be to introduce cumbersome one-way systems and force them to queue up outside…. how will people observe that rule on the pavement when there are queues outside every shop?”

The WHO messaging on face masks has also been confused and contradictory.

In a video on 24 March, WHO recommended wearing them; in updated advice on 6 April, WHO said the “use of masks by healthy people in the community setting is not supported by current evidence and carries uncertainties and critical risks”; on 5 June, WHO reverted to advising mask wearing for everyone in public.

We have had similarly absurd, inconsistent, and even contradictory advice in Australia from federal and state authorities, all supposedly based on the best science.

The tussle over state border closures is the most visible current example.

But previous incidences included prohibiting a mother and daughter, who live in the same house, from going for a driving lesson together in a sealed car; playing solo golf, sitting alone on a park bench, or enjoying a solitary walk on the beach or swim in the ocean; and driving to in-state holiday homes. Staying cooped up at home with others is the healthier choice. Really?

Meanwhile, it was permissible to wander around supermarkets and handle food and produce with no idea of how many others have handled it.

The Randomness of the Downward Infection Curves

The epidemiological experts have been sharply, and sometimes bitterly divided over the nature of the coronavirus curve, the comparative utility and futility of different mitigation and control measures, and how much weight to give to the collateral damage being inflicted on other public health, economic, and liberal goals that together represent the social purpose of the state. Jonathon Fuller discusses the contrasting philosophies of scientific knowledge between epidemiologists who prefer models and those for “evidence-based medicine” in clinical practice.

The former advocate NPIs to flatten the curve; some of the latter subscribe to the notion of a “self-flattening curve,” as Stanford’s Nobel Laureate Michael Levitt put it. Oxford professor of theoretical epidemiology Sunetra Gupta holds that the strikingly similar patterns of the epidemic across countries (it grows, turns around, and dies away “almost like clockwork”) is better explained by pre-existing immunities to related coronaviruses such as the common cold, than by lockdowns or government interventions.

Figure 1 appears more consistent with the Levitt-Gupta thesis than the modelling thesis.

Contrasting Scandinavian Examples

The best-known example of a country bucking the model is Sweden.

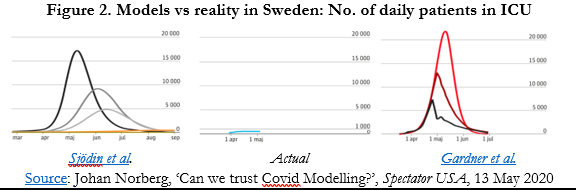

Without compulsory lockdowns and with much activity as normal, the country has not been decimated by the disease. Applied to Sweden, it was projected that, without a lockdown instituted by 10 April, between 70,000-90,000 people would die by mid-May.

The actual total on 30 May was 4,395 – significantly higher than its Nordic neighbours but behind lockdown countries Belgium, Spain, UK, and Italy and about the same as France in deaths per million people.

As with numerous other studies, that is, there is no clear evidence of the effectiveness of lockdowns. The two points of comparison – Nordic neighbours and other European countries – will be keenly watched over the coming months.

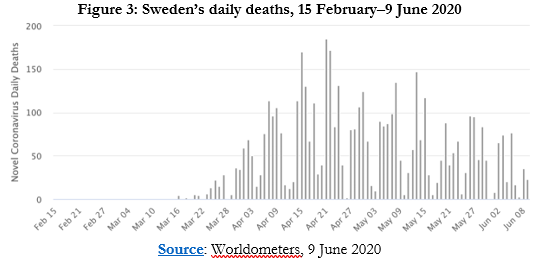

Figure 2 is visually stunning in dramatising the discrepancy between two epidemiological models on either side of the chart and the empirical reality in the centre. For all the flurry of domestic and international criticism directed at it, Sweden held its nerve and the results are there to see (Figure 3).

On 3 June, Swedish Radio published an interview with chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell in which he acknowledged the perfectly obvious fact that in retrospect, they could have handled the crisis better and in particular taken better precautions to protect the care homes where more than half of Sweden’s COVID-19 deaths have occurred.

This “was spun pretty hard” in the international media as a mea culpa on lockdowns. It was not. Tegnell explained to Dagens Nyheter that knowledge about COVID-19 is much better now and would be useful for improved mitigation, but he still doesn’t believe that lockdown would have been a better choice for Sweden: “the fundamental strategy has worked well.”

Critics of Sweden’s distinctive no-lockdown approach, some of whom seem almost to be willing Sweden to fail, resort to classic “whataboutery”: But what about its 4,717 deaths compared to its closest comparable neighbour Norway’s 239 deaths?

One could counterpose: what about lockdown Belgium with 9,619 deaths and, at 842 deaths per million people, the highest death rate in the world?

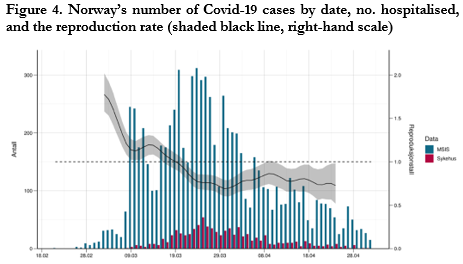

Dr Camilla Stoltenberg, Director-General of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, said on 22 May that the country could have controlled the virus without lockdown.

Speaking to the state broadcaster about the release of a new report from her institute, she said: “Our assessment now…. is that we could possibly have achieved the same effects and avoided some of the unfortunate impacts by not locking down, but by instead keeping open but with infection control measures.”

Norway’s reproduction number had fallen to 1.1 before the lockdowns were announced on 12 March (Figure 4). “The scientific backing was not good enough,” she added, to warrant the hard policies, in shades of the WHO’s 2019 advice.

Ramesh Thakur FAIIA, a former Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, is Emeritus Professor of the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University. He is Director of the Centre for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament and co-convener of the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament.

This is part one of a two-part article on the need for a critical assessment of national responses to the pandemic.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and was first published in The Australian Institute of International Relations.

Editors Note: With courts banning protests around Australia and the Prime Minister Scott Morrison calling for protesters to be arrested we have seen the abandonment of the democratic right to protest and the imposition of what amounts to martial law. As whistleblower Edward Snowden has warned, nothing had been more gamed by the world’s intelligence agencies than a pandemic and governments are highly unlikely to let go of the powers they have now seized.

But the military mindset behind much of what we are seeing in Australia and their failure to understand civilian populations could well prove the government’s own undoing.

Since the beginning A Sense of Place Magazine has loudly and consistently warned that government actions were likely to do far more damage to Australian society than the virus ever could.

FEATURED BOOKS

2 Pingbacks