Tag A Sense of Place Publishing

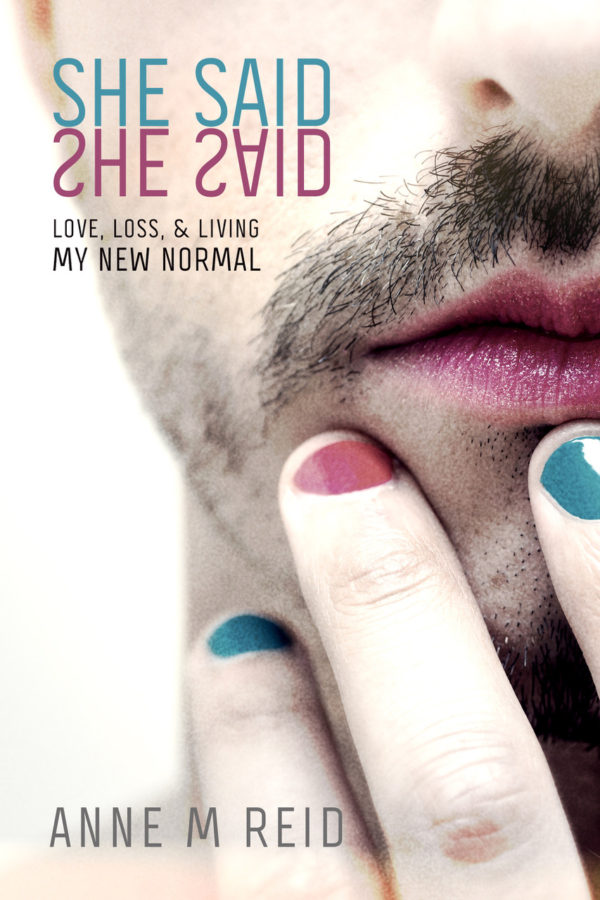

A Sense of Place Publishing is proud to announce the forthcoming publication of She Said She Said.

The ordinary and the extraordinary mix in this excruciatingly intimate, and at times triumphant and funny book which tells a profoundly moving story which could have been custom built for our times.

Anne M Reid had the perfect life with her perfect partner. She and Paul were together for 12 years, married with three beautiful children.

One night, without warning, Paul reveals that as a young child, he had wanted to be a girl. He had felt a total disconnection with his body and at one stage tried to castrate himself.

The book explores the nightmare Anne faced as Paul transitions to Paula, initially with hormonal treatment and eventually surgery. Anne’s husband not only had a new sex, but a new personality, different likes and dislikes, and a different take on the world. The husband she knew simply vanished and a stranger emerged.

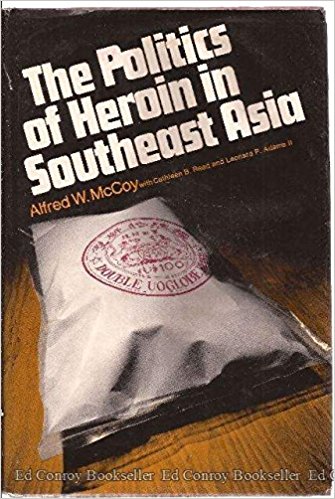

The Politics of Heroin in S.E. Asia, first published in 1972, was a landmark book on the heroin trade, and easily one of the most insightful books ever written on the subject. Dr Alfred McCoy is revered by journalists and fellow researchers alike, and continues to write superbly on the difficult subject of the heroin trade.

His first book on the subject was followed by The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade. Here the world’s foremost expert on the subject explains how heroin is behind the multi-faceted disaster which is the war in Afghanistan.

After fighting the longest war in its history, the US stands at the brink of defeat in Afghanistan. How could this be possible? How could the world’s sole superpower have battled continuously for more than 16 years – deploying more than 100,000 troops at the conflict’s peak, sacrificing the lives of nearly 2,300 soldiers, spending more than $1tn (£740bn) on its military operations, lavishing a record $100bn more on “nation-building”, helping fund and train an army of 350,000 Afghan allies – and still not be able to pacify one of the world’s most impoverished nations? So dismal is the prospect of stability in Afghanistan that, in 2016, the Obama White House cancelled a planned withdrawal of its forces, ordering more than 8,000 troops to remain in the country indefinitely.

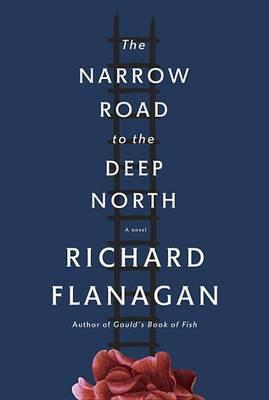

Months after it won the Man Booker Prize for 2014, Richard Flanagan’s masterful novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North remains in the best seller lists. Set in the Japanese Prisoner of War camps in Thailand during World War Two, it is a beautifully written, heart gripping wrench of a book, up there with Sebastian Faulk’s Birdsong as one of the most powerful war novels of all time. Here is the acceptance speech by author Richard Flanagan for winning the Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for his masterful novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

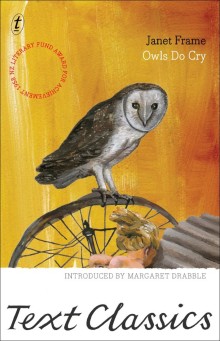

There has been no more beautiful writer in the history of the English language than Janet Frame. Her natural poetic gifts, combined with a close documentation of her own psychic disturbances, produced a densely layered, intensely lyrical prose without peer.

What could possibly be funny about two Tibetan boys climbing a mountain behind their village and finding a very strange object? Would any sane person laugh when the object turned out to be a time capsule created by an advanced civilisation over 300,000 years ago? And what about when the time capsule produces a hologram showing an enlightened society built on the principle of empowerment, a society which managed to destroy itself? Fantasy, the fantastical and the all too true combine in this romp through the ages.

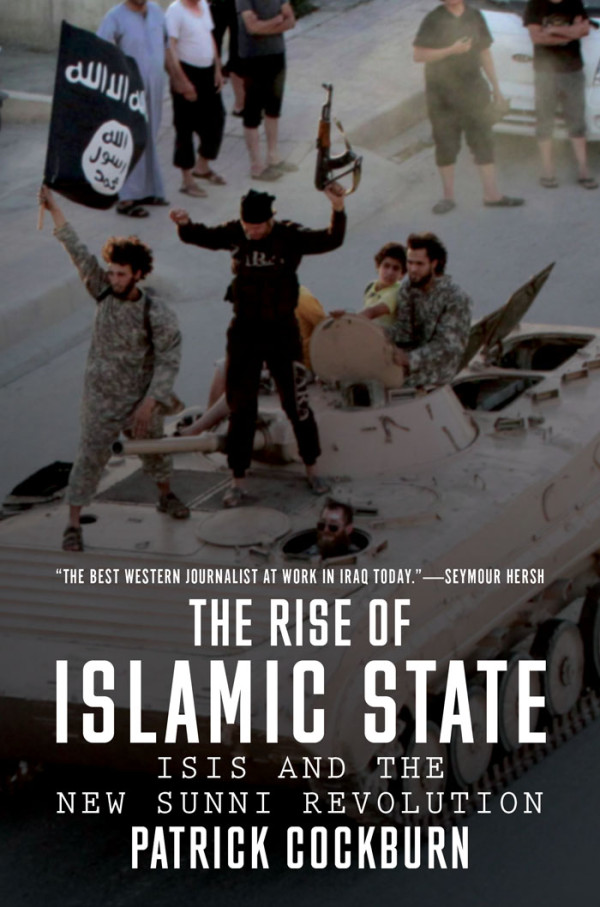

The Rise of Islamic State, written by senior Middle Eastern correspondent Patrick Cockburn, explores the origins of history’s most successful terrorist group and the unfolding of US and the West’s greatest foreign policy debacle. In military operations, by mid 2014 they had outreached Al Qaeda, taking territory that reached across borders and included the city of Mosul. The reports of their military power and brutality to their victims continue to shock and intimidate the West. Out of the failures of Iraq and Afghanistan, the Arab Spring and Syria, a weakened Al-Qaeda has allowed for new jihadi movements, especially Islamic State.

Some 150,000 people have returned to Raqqa, though they are not very visible on the streets. A few shops have reopened but there not many customers and business is slow. Beside an ancient ruin called “The Ladies’ Castle”, Basil Amar as-Sawas has a shop selling doors, some of which he makes himself, while others he buys from people whose houses have been badly damaged but they have been able to salvage some of the fittings.He says there is little money around and those who have any are reluctant to spend it while the situation remains so uncertain. Some people whose houses have survived “are selling them to businessmen because they need the money”. He has two small children below school age but for other people the absence of schools – mostly destroyed or badly damaged – is another disincentive for thinking of a return to Raqqa.

Reminders of the grim rule of Isis are everywhere. The tops of the pointed metal railing surrounding the al-Naeem Roundabout are bent outwards because that is where severed heads were put on display.

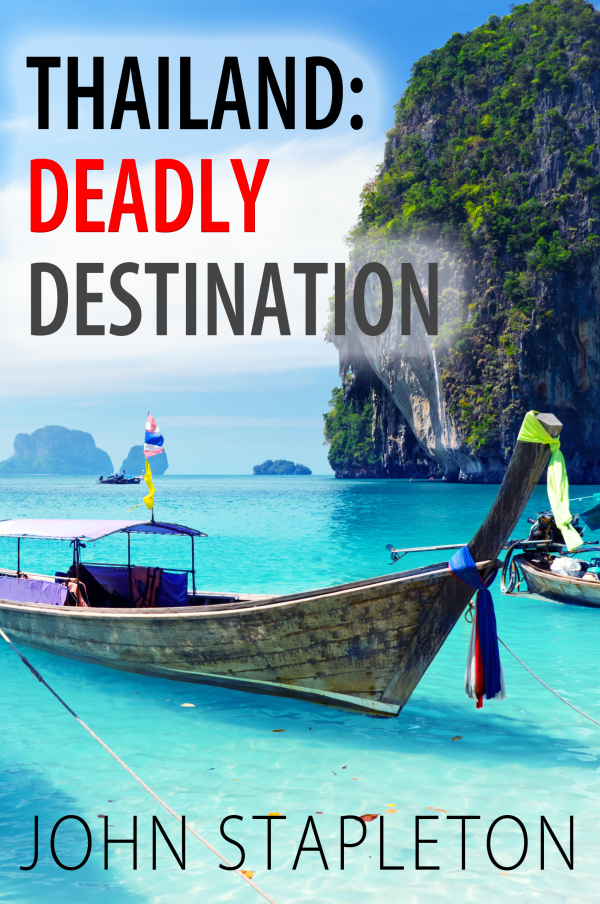

Thailand: Deadly Destination exposes the worst scandal in the annals of modern tourism, the high number of deaths of foreigners in the so-called Land of Smiles.

Could it happen again? Of course it could. It already is. Here is an extract from John Koehler’s authoritative book Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police.

“The Stasi was much, much worse than the Gestapo, if you consider only the oppression of its own people,” according to Simon Wiesenthal of Vienna, Austria, who has been hunting Nazi criminals for half a century. “The Gestapo had 40,000 officials watching a country of 80 million, while the Stasi employed 102,000 to control only 17 million.” One might add that the Nazi terror lasted only twelve years, whereas the Stasi had four decades in which to perfect its machinery of oppression, espionage, and international terrorism and subversion.

Compelling, groundbreaking and immensely readable, The Story of Australia’s People: The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia, is the first installment of an ambitious two-part work, and the culmination of the life work of Australia’s most respected historian Geoffrey Blainey. The vast, ancient land of Australia was settled in two main streams, far apart in time and origin.The first stream of immigrants came ashore some when the islands of Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea were one. The second began to arrive from Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. It was not – and is still not – an easy relationship, and the story of Australia’s people is complex. Gifted with a profound spirituality deeply attached to the land and a sense of place, Australia’s ancient people were devastated by the encroachments on their land, their proud and enduring tribal cultures utterly destroyed. Through their European notions of private property, their animals, the rabbit, alone, has transformed the landscapes of Australia from one end of the continent to the other, while their foxes and cats have destroyed native wildlife which had survived for countless generations. The arrival of Europeans was all about the brutality of invasion. And the Europeans, and now a polyglot rush of people from all over the world, those who opportunistically grafted themselves on to this ancient land, have proved they have learnt nothing: throughout the past Century Australia has been party to wars on foreign lands, and is party to the utter debacle that is the invasion of Iraq.

Margaret Atwood wrote in her tribute to the author of The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K Le Guin: I am very sad that Ursula K Le Guin has died. Not only was she one of the literary greats of the 20th century – her books are many and widely read and beloved, her awards are many and deserved – but her sane, committed, annoyed, humorous, wise and always intelligent voice is much needed now.

Right before she died, I was reading her new book, No Time to Spare, a collection of trenchant, funny, lyrical essays about everything from cats to the nature of belief, to the overuse of the word “fuck”, to the fact that old age is indeed for sissies – and talking to her in my head. What if, I was saying – what if I write a piece about The Left Hand of Darkness, published by you in 1969? What if I say it’s a book to which time has now caught up?

Consider: the planet of Gethen is divided. In one of its societies, the king is crazy. Cabals and personal feuds abound. You’re in the powerful inner circle one day, an outcast the next. In the other society, an oppressive bureaucracy prevails and a secret committee knows what’s best. If judged a danger to the general good you’re deemed persona non grata and exiled to a prison enclave, with no trial or right of reply.

Buy Now

America’s war in Afghanistan is the longest war the U.S. has ever fought. Beginning a month after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the initial mission was to remove the Taliban from power and destroy the al-Qaida terror network. Now, nearly 17 years later, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Steve Coll points out in his new book Directorate S: The CIA’s Secret War in Afghanistan and Pakistan, that the war’s goals have changed.

At best the war is a grinding stalemate.

“The prison was a hell on earth, as I will attempt to show in these pages, but I’m afraid my words will never be up to the task of conveying the filth, the danger, the uncertainty, the noise, the stench, the hopelessness, the barbarity, the cheapness of life, the random violence, the anguish, and the sheer fucking boredom that I had to wade through day after day, more than two thousand days and nights, in what should have been my prime.”

To the Edge of the World is an adventure in travel full of extraordinary personalities, more than a century of explosive political, economic, and cultural events, and almost inconceivable feats of engineering. Christian Wolmar passionately recounts the improbable origins of the Trans-Siberian railroad, the vital artery for Russian expansion that spans almost 6,000 miles and seven time zones from Moscow to Vladivostok. The world’s longest train route took a decade to build in the face of punishing climates, rampant disease, scarcity of funds and materials, and widespread corruption.

A Sense of Place Publishing is proud to announce the forthcoming publication of Sorry Time by Anthony Maguire. The book is action packed from the get-go, beginning with murder and revenge in a compelling and merciless outback. The breakneck story is tailor made for film and this quality ensures a visually rich and entertaining reading experience.

You’re driving along a lonely outback road when suddenly a kangaroo leaps out in front of you. Your car is wrecked and then things rapidly go downhill from there as you find yourself under attack from a pack of wild dogs. Having survived that, you cross bloody paths with a pair of violent criminals – brothers Ali and Abdul Fazir – who’ve murdered two people on a remote Aboriginal community.

Alan Lightman’s The Accidental Universe: The World You Thought You Knew is a book about nesting ospreys, multiple universes, atheism, spiritualism, and the arrow of time. He takes the reader back and forth between ordinary occurrences-old shoes and entropy, sailing far out at sea and the infinite expanse of space. He looks toward the universe and captures aspects of it in a series of beautifully written essays, each offering a glimpse at the whole from a different perspective: here time, there symmetry, not least God. It is a meditation by a remarkable humanist-physicist, a book worth reading by anyone entranced by big ideas grounded in the physical world.

A Sense of Place Publishing is proud to announce the forthcoming publication of She Said She Said by Australian born American author Anne Reid. The ordinary and the extraordinary mix in this funny, moving, excruciatingly intimate, triumphant book which soars… Continue Reading →

Award-winning former NPR correspondent, foreign policy expert, and associate at the Carnegie Endowment, Sarah Chayes has an urgent warning in her new book Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens National Security. Militant puritanical religion is presenting as a just alternative to depraved secular rule.

Something Wicked This Way Comes. It most certainly does. We are entering a new age of book burning, where ideas are ridiculed, contrary views cannot be debated, and governments reach for their only tool, crackdowns in the march towards totalitarian states. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 was an entirely prophetic novel, and now sits alongside George Orwell’s 1984 as a book which predicted a future no-one truly expected to see, the closing of minds and the subjugation of dissent in the 21st Century. Here are some brief extracts.

It was a pleasure to burn.

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.

Despite the billions of dollars funnelled to them, and their thousands of personnel, Australians know almost nothing about the well-resourced, ultra-secretive intelligence agencies their dollars support. This is against a backdrop where the government has greatly expanded the powers of the agencies, but the citizens themselves have few legal rights when it comes to those who spy so avidly upon them.

There is no legal right to privacy or freedom of expression written into the Australian constitution, and the government has a reputation for spying on its own citizens to a far greater degree than any other Western democracy.

With the multiple incompetencies of Australian governance now a byword across the nation, transparency at zero and oversight chaotic at best, Australians can only take the word of their politicians on the value of these agencies, routinely described by the Prime Minister of the day as “the best in the world”.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull flew in the face of opposition from the agencies themselves and many of his most senior ministers, when he announced the formation of a new Homeland Security style mega-agency.

Reviews of the nation’s security agencies are extremely rare. While a determinedly “inside the beltway” view, with almost no public input, the new Independent Intelligence Review, when read with a certain between-the-lines scepticism, is a valuable insight at a time when the entire future of intelligence in Australia is in play.

Visitors to Thailand are not warned by travel agents, airlines or their own governments that their passports are highly prized in Thailand, and stand a very good chance of being stolen. Depending on the nationality, a passport can fetch thousands of dollars on the black market, several months pay for many Thais. There are gangs stealing passports to order. European, American, Australian and Canadian passports are particularly prized. Foreign embassies, fearful the documents are ending up in the hands of Islamist militants and international criminal networks, have made repeated representations to the Thai government without affect. INTERPOL Chief, Secretary General Ronald Noble describes passport fraud as the “biggest threat facing the world”. But for decades the Thai authorities have done little to stop their country’s blatant trade in stolen, doctored and forged documents. By inaction and complicity, Thailand has become an epicentre for the trade, a key link in international terrorist networks and a danger to the travelling public worldwide. Forged passports from Thailand are regarded as the highest quality of any in the world. Clients from the Middle East are one of the major buyers of fake passports in Thailand. In The Age of Terror, the failure of the Thai authorities to abolish the trade has set alarm bells ringing around the world. Here in its entirety is Chapter Two, called Passports, from the recent book Thailand: Deadly Destination.

Writing in The Conversation, commentator Jen Webb records her reaction to the first major biography of Australian journalist and author Helen Garner: How remarkable that, after some 40 years of books and essays, stories, articles and movies, there have been so few major publications on the life and works of Helen Garner. The National Library of Australia catalogue lists discussion notes; a study (in Mandarin) by Zhu Xiaoying; and Kerryn Goldsworthy’s excellent 1996 monograph. Bernadette Brennan’s A Writing Life goes a considerable way to filling out this slender collection.

Brennan offers a detailed account of Garner’s writing life, tracing the influences and obstacles; psychological and emotional affordances and constraints; her research and craft; and the critical and popular reception of her books. This is a valuable contribution about a major contemporary Australian writer who has delighted, infuriated, confused, charmed and frustrated readers, and whose experimental practice has galvanised ways of writing and thinking about writing.

On her literary blog Brain Pickings the incomparable Maria Popova writes: 1915 paper on general relativity, Albert Einstein envisioned gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by astronomic events of astronomical energy. Although fundamental to our understanding of the universe, gravitational waves were a purely theoretical construct for him. He lived in an era when any human-made tool for detecting something this faraway was simply unimaginable, even by the greatest living genius, and many of the cosmic objects capable of producing such tremendous tumult — black holes, for instance — were yet to be discovered.

One September morning in 2015, almost exactly a century after Einstein published his famous paper, scientists turned his mathematical dream into a tangible reality — or, rather, an audible one. In Black Hole Blues and Other Songs from Outer Space — one of the finest and most beautifully written books I’ve ever read — astrophysicist and novelist Janna Levin tells the story of LIGO and its larger significance as a feat of science and the human spirit. Levin, a writer who bends language with effortless might and uses it not only as an instrument of thought but also as a Petri dish for emotional nuance, probes deep into the messy human psychology that animated these brilliant and flawed scientists as they persevered in this ambitious quest against enormous personal, political, and practical odds.

At once highly intelligent, with a clear eye for commonality and nuance and life as it is lived, set in broader rivers, with an eagle’s eye for beauty and a highly accomplished prose style, Australia’s preeminent observer of indigenous Australia Nicolas Rothwell has a new book out, Quicksilver.

Here is an extract:

Leo Frobenius, the great impressario of German imperial ethnography, conceived the idea that the Kimberly region of North-West Australia could serve as a window onto the fast-vanishing primeval past of man.

An expedition by the Frobenius Institute arrived in Broome in 1938, under the leadership of a young specialist in Aboriginal and Oceanic societies named Helmut Petri. The team then traveled from Walcott Inlet deep inland through the territories of the Worora and the Ngarinyin. Their discoveries were spectacular; their timing was poor.

It was only nine years after the end of World War II that Helmut Petri was able at last to publish an abbreviated account of his findings.

“Sterbende Welt in Nordwest Australien”, The Dying World in North-West Australia, is a production of great beauty, shot through with overtones of mourning and grief. Petri regarded it as no more than a damaged torso, a fragment of the book he planned to write – but that fragmentary quality gives the work much of its force. Although it is ostensibly concerned purely with ethnographic description of remote tribes and their social adaptations, it is in fact a study of a culture under stress and in collapse, and when I first came across it and made my way through its pages I at once felt it held the key to any truthful understanding of north Australia’s first civilizations and their fate.

I don’t know that I believe in the existence of God in the Catholic sense. But my favorite book is the Divine Comedy. And at the end of the Divine Comedy, Dante pierces the skin of the universe and comes face-to-face with the love that moves the sun and the other stars.

I believe that there is a love that moves the sun and the other stars. I believe in Dante’s vision.

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Joby Warrick reveals in Black Flags: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of The Islamic State how the stain of militant Islam now raising its banner across Iraq and Syria spread from a remote Jordanian prison with the unwitting aid of American military intervention. When he succeeded his father in 1999, King Abdullah of Jordan released a batch of political prisoners in the hopes of smoothing his transition to power. Little did he know that among those released was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a man who would go on to become a terrorist mastermind too dangerous even for al-Qaeda and give rise to an Islamist movement bent on dominating the Middle East. Zarqawi began by directing hotel bombings and assassinations in Jordan from a base in northern Iraq, but it was the American invasion of that country in 2003 that catapulted him to the head of a vast insurgency.

Alastair Bothwick Nicholson, Chief Justice of the Family Court Australia from 1988 until 2004, is the dominant figure in the history of family law in Australia.

While the Family Court is deliberately kept out of the arena of contemporary public debate, it was not always so.

The Final Days of Alastair Nicholson: Chief Justice Family Court of Australia covers a period of intense media coverage and fervent hope that the troubled jurisdiction would be reformed.

Those dreams were dashed, with the then Prime Minister John Howard ignoring public support for shared parenting and a shift away from the traditional sole custody model.

The marginalisation and demonisation of fathers stood oddly with the country’s egalitarian traditions.

If you think you’re under surveillance, you more than likely are. Australia has a long history of surveying its own citizens, well beyond that of comparable Western countries. Described by its critics as a secret parallel police force which has done enormous harm to Australian democracy, The Australian Security Intelligence Service is forever a source of fearful fascination for Australians.

Its new offices in Canberra are almost as imposing as Parliament House itself.

Since 9/11 the agency has been gifted billions of dollars. Yet its operations completely lack transparency.

In the last budget the Turnbull/Abbott government gifted them yet more hundreds of millions of dollars, yet it is a secret as to exactly how much!!

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy, by Francis Fukuyama, is the story of how state, law and democracy developed after these cataclysmic events, how the modern landscape – with its uneasy tension between dictatorships and liberal democracies – evolved and how in the United States and in other developed democracies, unmistakable signs of decay have emerged. Best known for his book The End of History and the Last Man, Fukuyama argues that if we want to understand the political systems that dominate and order our lives, we must first address their origins – in our own recent past as well as in the earliest systems of human government. He believes the key to successful government can be reduced to three key elements: a strong state, the rule of law, and institutions of democratic accountability. Essential reading for anyone wishing to understand why Western democracies are so vulnerable to the Sharia.

Travel the world with Eric Weiner, the New York Times bestselling author of The Geography of Bliss, as he journeys from Athens to Silicon Valley—and throughout history, too—to show how creative genius flourishes in specific places at specific times. In The Geography of Genius, the acclaimed writer sets out to examine the connection between our surroundings and our most innovative ideas. He explores the history of places, like Vienna of 1900, Renaissance Florence, ancient Athens, Song Dynasty Hangzhou, and Silicon Valley, to show how certain urban settings are conducive to ingenuity. And, with his trademark insightful humor, he walks the same paths as the geniuses who flourished in these settings to see if the spirit of what inspired figures like Socrates, Michelangelo, and Leonardo remains.

Thailand ‘one of the most dangerous tourist destinations on Earth’: Expat investigation lifts lid on dark side of the Land of Smiles

Thailand: Deadly Destination penned by Australian author John Stapleton

Writer says tourism boom has created hatred and contempt for foreigners

Death rate of tourists is ‘worst scandal in the annals of modern tourism’

Murder of British backpackers followed military coup in May this year

Ministry of Tourism forecast 25m visitors in 2015, down from 30m last year

By SIMON CABLE FOR MAILONLINE

PUBLISHED: 20:18 AEST, 15 November 2014 | UPDATED: 01:08 AEST, 17 November 2014

A new book has branded Thailand one of the world’s most dangerous tourist destinations.

Australian author John Stapleton suggests that widespread police corruption, violence and crime are all blighting a country once commonly referred to as the ‘Land of Smiles’.

In his book Thailand: Deadly Destination, Mr Stapleton attempts to expose the reputation of Thailand as a welcoming country, claiming a boom in tourism since the 1960s has created a hatred of foreigners and a ‘murderous indifference’ to the millions of tourists who flock to the country’s white-sand beaches, picturesque countryside and thriving nightlife each year.

The country’s much-prized tourist industry, which accounts for 10 percent of the GDP, is in decay following more than 12 months of political unrest

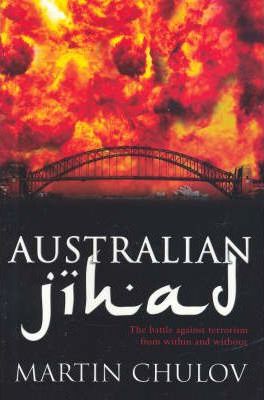

The best book ever written on jihad in Australia, by the supremely gifted journalist Martin Chulov, remains an under-reviewed and under-appreciated work.

As Chulov writes, Australia has been far more central to the international jihad movement than previously realised; and this book is a significant player in bringing that to light.

With legal suppression orders following Operation Pendennis and the 2005 planned attacks on the Melbourne Cricket Ground, Australian Jihad: The battle against terrorism from within and without, was withdrawn. For many years copies were almost impossible to find. A book which, far from being suppressed, should have been taught in the schools and universities and been mandatory reading for every politician thrumming the drumbeat of terror.

A barrister claimed the book could prejudice the trial of his client, although the basis for the book was previously published news stories from the national newspaper The Australian, where Martin Chulov then worked.