Extract: By Meredith Burgmann and Nadia Wheatley

We stand in Sydney’s Town Hall Square, two women in our seventies, holding handwritten placards. Meredith’s says, ‘Remember John Pat. 1966–1984’. Nadia’s says, ‘Solidarity! Black Lives Matter’.

We have stood here before, many a time, for a variety of campaigns and causes. But this time is a bit different. After weeks of lockdown, it feels surreal to be outdoors and in a crowd, but the oddest thing is that, as we look at the faces (mostly masked) around us, we see no one whom we know. Indeed, there seems to be no one else here over the age of forty. We find it a cause for optimism that our generation of Sixties radicals is not irreplaceable.

From the microphone at the top of the steps, speeches crackle, interspersed by periodic bouts of chanting. Around us, a sea of red, black and yellow surges and swirls. The recent death in the United States of George Floyd and the subsequent protests by the Black Lives Matter movement have given a new edge to the Aboriginal campaign against deaths in custody, which has been running since the 1980s.

‘Too many coppers, not enough justice!’ the chant rises.

‘Just like the old days’, we agree as we survey the ranks of police.

But what was it that originally took the two of us onto the streets?

One of the best-known slogans of the Sixties is the claim that ‘The personal is political’.

Of course, in any era, people bring their personal history to their political life, but in this book we relate the personal stories of a number of Australians from our generation who – either in reaction to a particular Sixties issue or simply in response to the zeitgeist – rejected the political views and values of their family, school, church and class. These radical about-turns were often accompanied by epiphanies, awakenings, revelations and other such ‘aha’ moments.

Five decades on, radicalism has developed a right-wing and pejorative association. But for us, it means openness and freedom. It means the particular kind of grassroots organisation and New Left ideology that arose in opposition to the hierarchical structures and dogmatism of the Old Left. And it means fun, not fundamentalism.

It was this that the two of us were discussing a few years ago over dinner, when we came up with the idea of a book about the Sixties. After all, both our lives had been transformed over a short period in 1968, initially through our involvement in the anti-Vietnam movement, but soon through taking part in other campaigns.

To outsiders, witnessing our sudden donning of National Liberation Front badges and our increasingly frequent appearances at the Central Court in Liverpool Street, we probably seemed surprising radicals. Both of us were from middle class and politically conservative backgrounds. Both of us had been educated at single-sex private schools. Both of us were raised in the dreary puritanism of Sydney Anglicanism. But – as we relate in our own accounts in this book – there was a great difference, too, in our respective backstories.

Apart from any personal issues we might have brought to our activism, for both of us – as for all the comrades whose stories we tell here – the catalyst for our radicalisation was the shared experience of growing up in the political circumstances of Australia in the 1950s. Certainly, the ferment of the Sixties was an international phenomenon, and for young radicals from Berlin to Berkeley it represented some sort of reaction to a Cold War childhood. But in this country, there was a particular thing to drive us wild.

This was a person known to his supporters as ‘Ming’ and to his class enemies as ‘Pig Iron Bob’. Elected in 1949 to head the first Coalition government of the Liberal and Country parties, Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies cast a long shadow over the childhood and adolescence of our post-war generation.

It is easy to point to the Menzies government’s support for policies such as White Australia and Assimilation, not to mention the military commitment in Vietnam, but just as bad was the cultural repression. Growing up behind the white picket fence of Menzies’ Australia was deadly boring.

Often unable even to say what was wrong, we knew had to make our escape, using whatever resources we had.

Whereas Millennials can express their views by way of Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, most of us did not even have what we called ‘a telephone’ (now known as a landline) in our cockroach-infested share houses and bed-sits. If we had a message too long to graffiti onto a wall, we had to type it onto a wax stencil, and then crank out inky copies on a duplicating machine.

Or we could go onto the streets and seize front-page headlines by getting bashed and arrested by police. That was social media, in the Sixties.

*

While Australian radicalism of the Sixties was a diverse phenomenon, the stories included here give a sense of its range. In this eclectic mix, there is a Maoist, an Anarchist and a Trotskyist, as well as a number of people who (like us) were lower-case socialists, communists and anarchists, or a mix of all three. Others were not aligned with any particular ideology. There are two lesbians and a gay man, and a plethora of feminists. Australia in the Sixties was by and large an Anglo monoculture and this is reflected in the backgrounds of our guests, but there are three people whose families had recently arrived from Europe, and there are three First Australians.

For all of these individuals, the crucial thing that would shape their lives was the spirit of the Sixties.

That spirit was a powerful and heady mix of street marches and sit-ins, of sexual liberation, of music (folk and rock), combined with alcohol and/or drugs (which, in those halcyon days, were mostly fairly gentle). This was reinforced by a particular type of comradeship shaped by the experience of living in crowded share houses together, handing out leaflets together, getting arrested together, boozing together or getting stoned together, and singing Spanish Civil War songs together. Although there were schisms and divisions between followers of different ideologies and factions, we all believed we could change the world. And we did!

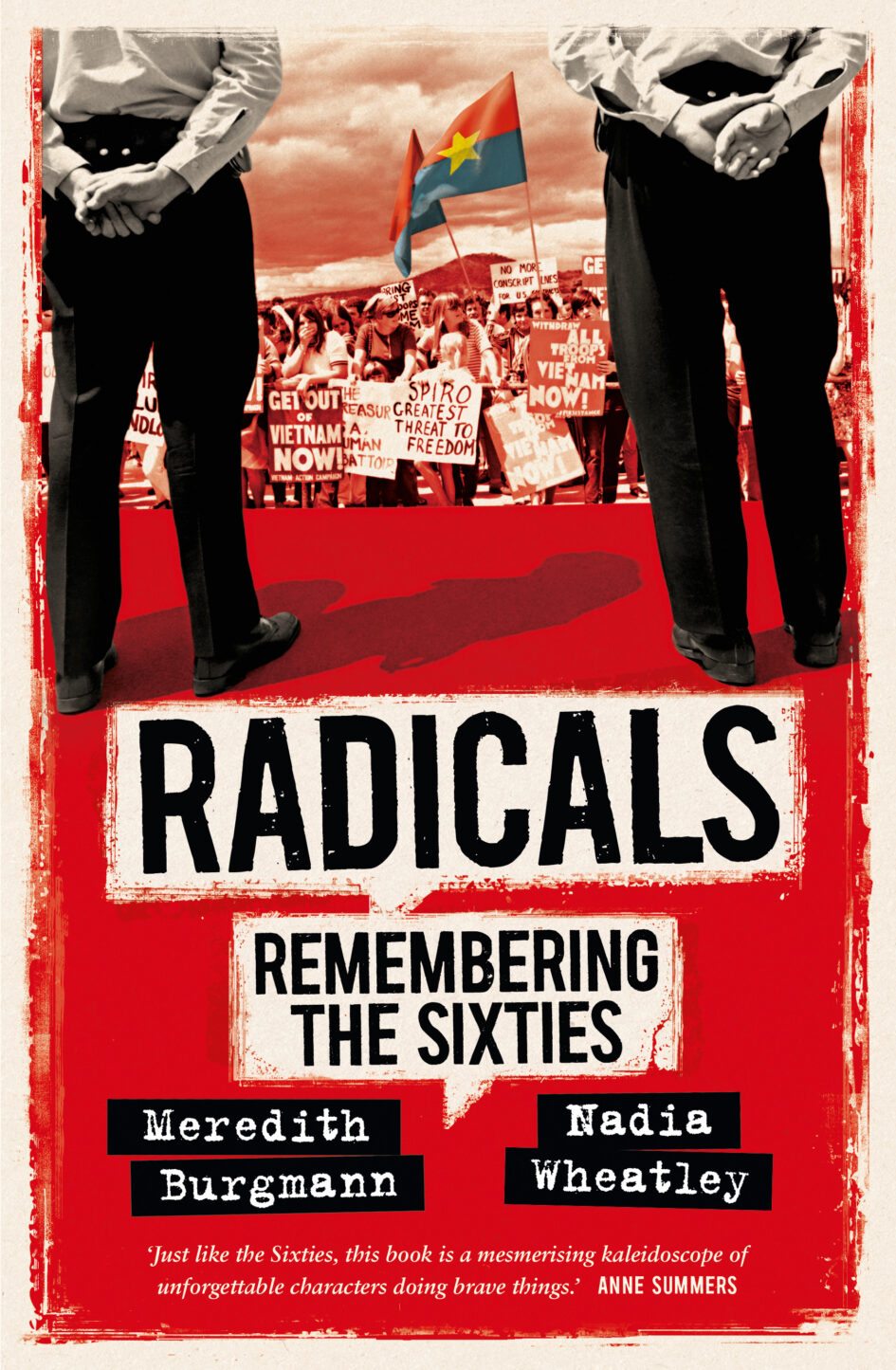

Radicals can be purchased from Australia’s largest online store Booktopia or the UNSW Bookshop.