By Colin Chapman

Harold Evans had an indefatigable role in encouraging and expanding coverage of international affairs in the publications he edited and in the books he published. He also had great enthusiasm for hiring and fostering well-trained Australian journalists.

Tens of thousands of words have been written or broadcast worldwide to commemorate the life of Harold Evans, arguably the most outstanding, transforming, and crusading editor of his generation. Sir Harry has died aged 92 in New York last month after achieving the twin pinnacles of global journalism and publishing.

This, the New York Times suggested, was achieved through “relentless independence, innovative ideas, and an appetite for risk that led to post-war changes in journalism, publishing, and public tastes.”

Most obituaries paid tribute to Evans’ courage in taking on the political and legal establishments, his buccaneering style, and an obsession with journalism based on facts.

I have personal recollection. It was Harry who triggered my 50-year career in geopolitics and geoeconomics. At the start of 1967, I had just returned to my Fleet Street job as education correspondent of The Sunday Times after four months in the United States as the first journalist Winston Churchill Fellow. The opportunity allowed me to investigate race problems, desegregation in the school system, and Beltway politics.

In my absence, the paper’s owner and benefactor, Lord Thomson of Fleet, had taken over The Times, the so-called “top peoples’ daily,” which had become burdened with crippling losses and a small circulation.

Thomson made The Sunday Times’ editor Denis Hamilton editor-in-chief of both newspapers. A shrewd and canny operator of military bearing (he had been aide-de-comp to General Montgomery in World War II), Hamilton named Evans, the young acclaimed editor of The Northern Echo, a regional daily based in Britain’s deprived north-east, as his successor.

Eyebrows were raised among some of the well-bred established grandees that the son of a Liverpudlian train driver who left school at 15 should be given the editor’s chair. But Harry quickly won them over, appointing one of them as his trusted deputy.

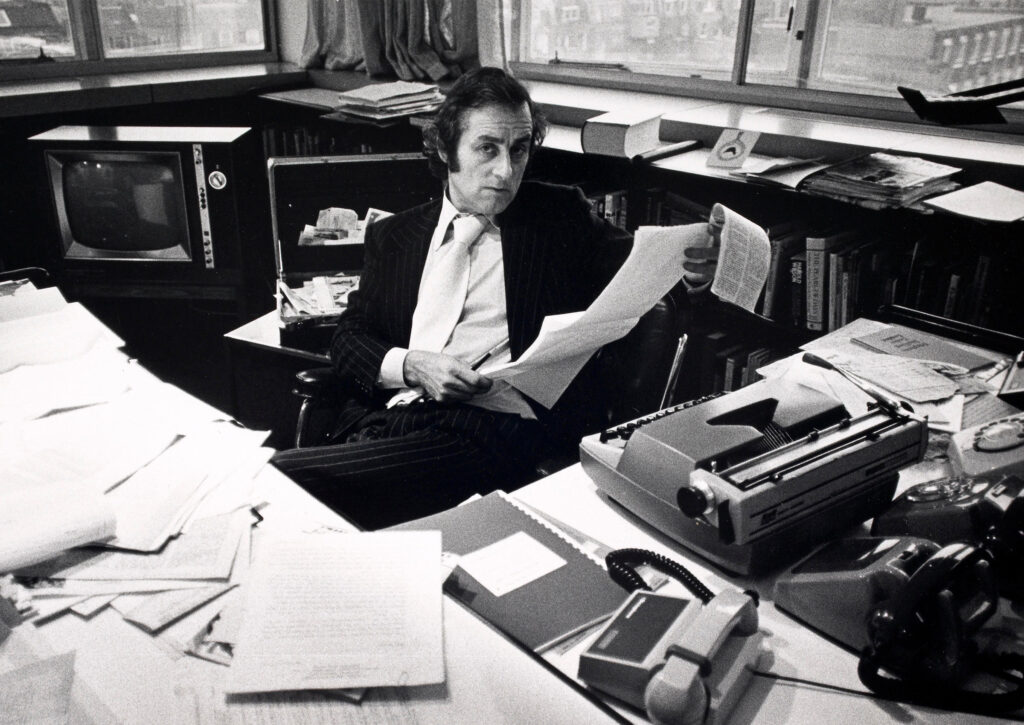

With the help of a generous budget which Hamilton had agreed with Lord Thomson, Evans set to work redesigning the paper and focusing on long-term investigative journalism and a big expansion in international news and analysis. I was fortunate to become the beneficiary of the latter.

When Harry posted a notice inviting staff to apply for the newly created post of foreign news editor, I got the job. I’d argued that although the paper had distinguished and well-connected veteran correspondents in places like Washington and Hong Kong (Henry Brandon and the Australian Richard Hughes, respectively), much of The Sunday Times’ foreign coverage was filtered through diplomatic channels and the Foreign Office. The paper needed much more factual on-the-ground reporting from the world’s trouble spots, particularly in Eurasia, the Middle East, and Africa. Harry wanted this to be intelligent, eye-witness reporting coupled with analysis from those closest to the events – whether political, military, revolutionary, or evolutionary.

We were fortunate with our timing. There were major wars in the Middle East, Vietnam, and Nigeria; a global campaign against apartheid in South Africa; rising tension in the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union; Mao Zedong’s great proletarian Cultural Revolution; the fight for African majority rule in former colonies, particularly Zimbabwe; the Watergate scandal and the controversial election of president Richard Nixon in the US; the expansion of the European Community beyond its original six; and the ever-present concerns of nuclear war. International news challenged the domestic agenda, and Harry’s demand was for us to be the best.

Correspondents who became award-winning legends were on the team: Murray Sayle, Phillip Knightley, Tony Clifton, David Leitch, Antony Terry, Nicholas Tomalin, and David Holden among them. They produced journalism of the highest quality, inspired by Harry’s energetic enthusiasm and the skillful way it was presented week by week, supported by a brilliant picture desk, maps, and graphics. Their long, comprehensive reports leapt out of the page.

Two of the correspondents died in the line of duty – Tomalin was killed by a guided missile on the Golan Heights in Syria while reporting on the Arab-Israeli war; David Holden, chief foreign correspondent and a Middle East specialist, was murdered in unknown circumstances. His body was found dumped on the roadside close to a university campus in Cairo, and Harry sent members of his Insight team to investigate, telling one of them: “Take care, Mossad is the best secret service in the world.” To this day, Holden’s assassins have never been identified.

Of the correspondents named above, the first three were Australian. Harry liked recruiting Australian journalists – he recognised the quality of the cadetship training system that prevailed in Australia at the time (long before today’s patchy media studies degrees), and their reputation for inquisitiveness and persistence that matched his own.

Many formed part of the Insight team. In addition to Knightley and Clifton, they included Alex Mitchell, Nelson Mews, and Bruce Page, the brilliant Insight editor who had arrived from the Melbourne Herald. Their work was to appear not only in The Sunday Times, but also in best-selling books whose publication was encouraged and supported by Harry. Perhaps the most notable were the sensational outing of Kim Philby, a former Foreign Office official, as a Russian spy (Philby: The Spy who Betrayed a Generation) and An American Melodrama, still the definitive account for historians of the 1968 presidential campaign that brought Richard Nixon to power.

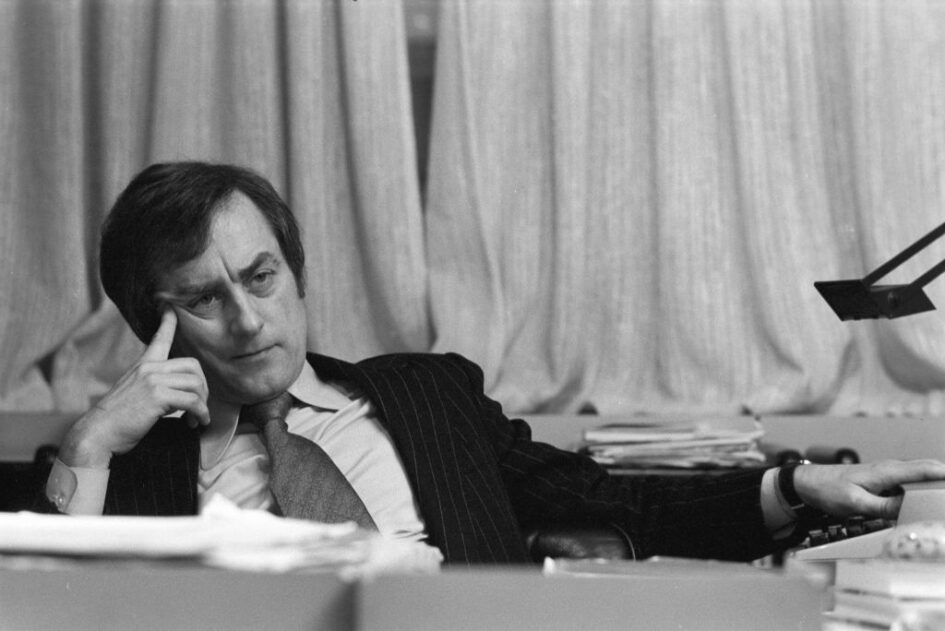

SALLY SOAMES/TIMES NEWSPAPERS LTD

He fought through the court’s UK government injunctions seeking to prevent publication of the revealing Crossman diaries, and published several financial exposes, including Do You Sincerely Want to be Rich, unravelling the crooked world of Investors Overseas Services, run by Bernie Cornfield. Another memorable revelation was the full story of the Bloody Sunday killings in Londonderry during the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

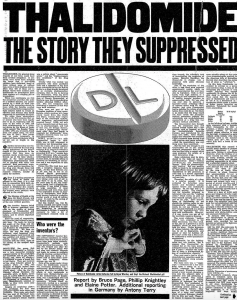

Australia was involved in the Insight campaign for which Harold Evans is best remembered – the eight-year battle to win justice for the 10,000 children born with appalling physical defects as a result of their mothers taking the anti-nausea drug thalidomide during pregnancy. Harry’s leadership in his campaign against the drug’s manufacturer, Distillers, and the legal and medical establishment was relentless in its determination to drive out the facts.

The Insight team’s inquiries led them to an Australian obstetrician, Bill McBride, who had alerted his British counterparts to the lethal character of thalidomide in a letter to The Lancet, a respected medical journal. McBride had noticed “multiple abnormalities” in babies born to women who had been prescribed thalidomide. After numerous court battles at the highest level, The Sunday Times revelations led to the drug being banned internationally and the victims being paid compensation. The British Medical Journal described the scandal as “one of the worst ever medical disasters.”

Evans also maintained connections with leading Australian media. The Age in Melbourne republished many The Sunday Times articles, and Evans became a friend and admirer of Graham Perkin, who edited The Age in its finest years as one of the world’s ten greatest newspapers. Harry may have had a role in its selection as a member of the executive board of the International Press Institute, an organisation in which he was involved for most of his career. His speech on press freedom at its 60th anniversary is just one part of his personal dedication to this cause, today championed by Louisa Graham, director of the Walkley Foundation.

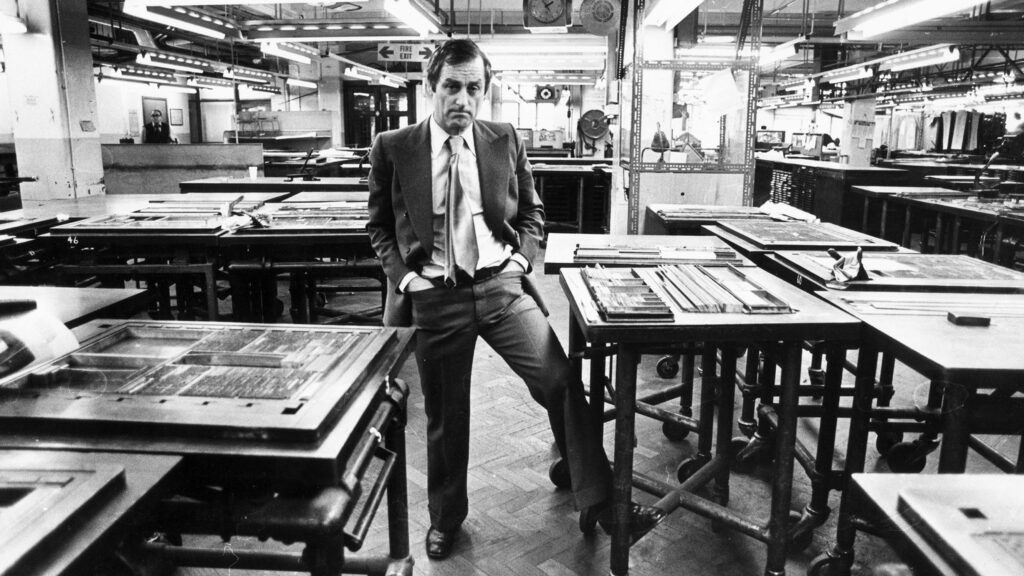

Harry’s UK career came to an end just over a year after the Australian-born Rupert Murdoch acquired Times Newspapers in 1981. It has been said that Murdoch moved him to the editorship of The Times because Harry was too dominant at the Sunday paper, his power base.

It is true that some of News Corporation’s bean counters in “Mahogany Row,” the company’s then Sydney headquarters, thought Evans overspent, pointing to the Private Eye jibe that “Harry will never send one reporter when he can send four.”

But I was deputy editor of The Australian at the time, and editing the paper when the transaction took place. While Dame Elisabeth Murdoch was delighted her son had added The Times to his stable, Mahogany Row was less elated. One concerned director told me. “You lot (at The Australian) are losing us money. The Times will lose us millions.”

Actually, Murdoch was very enthusiastic about Harry taking over The Times. He wanted him to shake it up, improve its appearance and broaden its appeal. The reason the relationship turned sour has been well documented, with both men culpable. The Times is now highly profitable, and outsells its once more powerful rival The Daily Telegraph by a wide margin. Harold Evans took off for New York with his magazine editor wife Tina Brown, and began a new career in publishing, rising inexorably to head the Random House group, where one of his many successes was Primary Colors, a novel authored anonymously, about the election campaign of the governor of a southern state. The chief character was modelled on Bill Clinton; sales soared as the literary and political world tried to guess the author’s identity. He was later identified as Joe Klein, a long-time Washington columnist. This was a typical Harry ploy – keep readers excited in anticipation of what comes next.

In remembering Harrys extraordinary achievements, it is perhaps fitting to conclude with his first big newspaper campaign on the Northern Echo when this small regional newspaper fought and won a long battle for a posthumous pardon for Timothy Evans, a young man with learning difficulties who was hanged for a murder he did not commit. Thereafter a search for justice was at the heart of everything Evans did.

Colin Chapman is a writer, broadcaster and public speaker, who specialises in geopolitics, international economics, and global media issues.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence. It was originally published by the Australian Institute of International Affairs.