By Paul Collits.

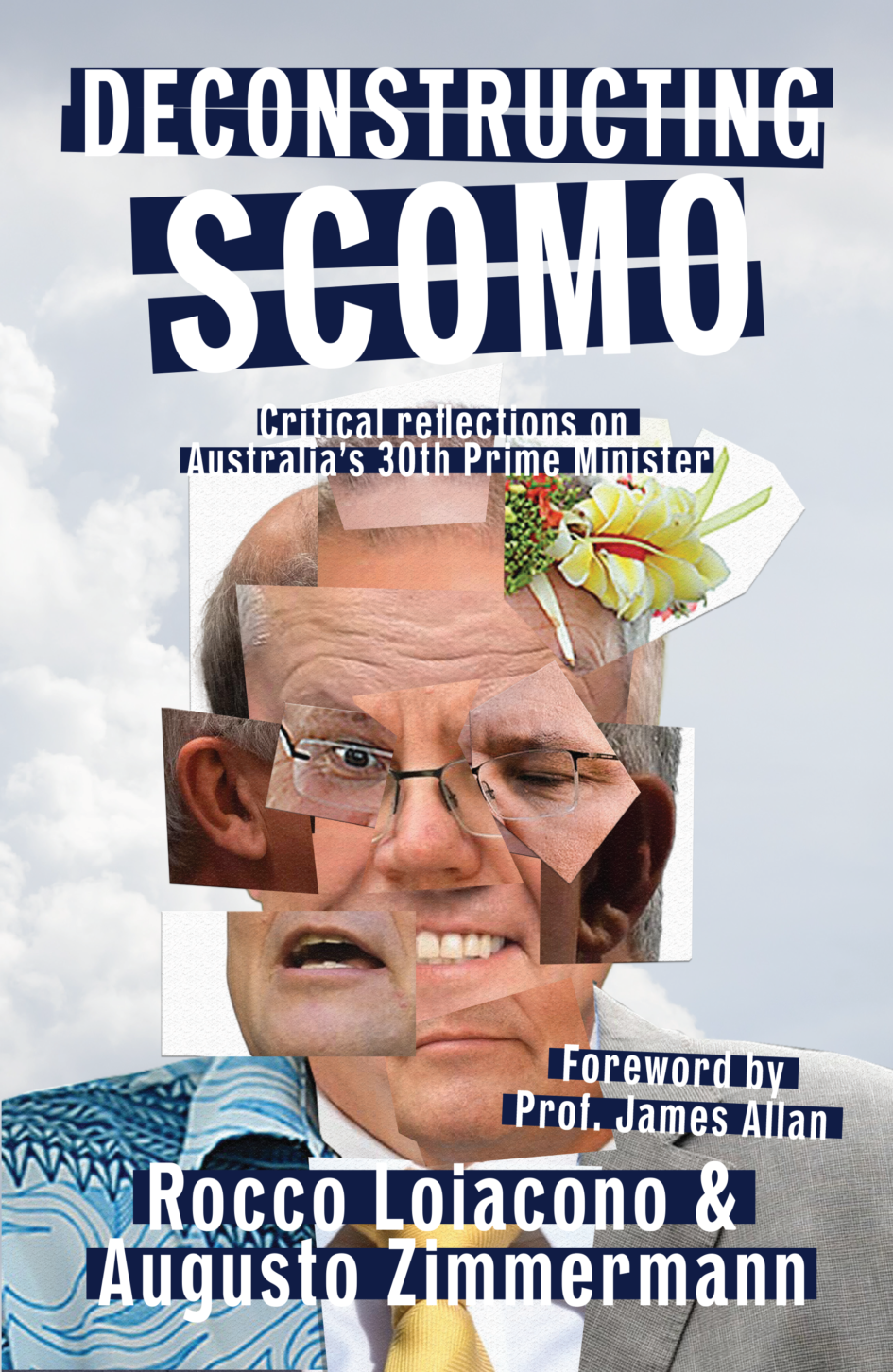

THE main problem with reviewing a book about Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison is that you have to read a book about Scott Morrison. But read it, one must.

Why should one read it? Well, I can think of three reasons. First, and most obvious, there is a federal election now, finally, called. Zimmermann & Loiacono are actually sympathetic to the values to which we might have expected Morrison to aspire to uphold.

It’s as if the PM goes out of his way to offend those he most needs.

He’s pathologically driven to avoiding offending anyone, that is, apart from his base.

ScoMo is Labor-heavy, but, without even believing in the things he’s done that have wrought such damage.

We are now well and truly in campaign mode. Perusing anything that casts light on why Australians should or should not entrust government, again, to Morrison’s Liberal-led Coalition might be time well spent.

Second, on the face of it, one might wonder how such a vanilla politician warrants one book, let alone the four that have been written about him (The Accidental Prime Minister, by Annika Smethurst; How Good is Scott Morrison? by Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen; The Game, by Sean Kelly; and Plots and Prayers by Niki Savva.

DEFENSTRATION

Okay, the last one was about the defenestration of Morrison’s predecessor, Malcolm Turnbull, as well as being about ScoMo.

This new book, then, might provide fresh insights into the man who will shortly face the people again, and perhaps find something in the man that was not previously apparent.

Third, this book is clearly written by authors who are widely known to be to the Right-of-centre politically.

They are, indeed, truth-tellers and freedom-fighters who are, as respected scholars, likely to provide a different perspective to those of progressives or journalists or both. (Smethurst works for The Age. Kelly was an adviser to Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd. Savva is famous for being Savva. Van Onselen has occupied more positions than the Kama Sutra, but no one, I think, would see him as a Right-winger).

In contrast, Zimmermann and Loiacono are actually sympathetic to the causes for which many Australians might be assumed to have supported the Morrison Liberals, and to the values to which we might have expected Morrison to aspire to upholding.

These authors, unlike the other biographers/political observers, have as their main task marking Morrison’s performance as a liberal/conservative politician.

This is what makes this book very different to the others, and especially useful for a conservative or liberal-inclined voter or simply anyone seeking to find and support someone who means what he says, says what he means, keeps promises, stands for something other than his own perennial re-election, treasures the core interests of voters, avoids endlessly spouting cliches, and doesn’t pander to mates.

In his foreword, another legal scholar highly critical of the current Prime Minister, James Allan, gets quickly to the nub of the book: “In these non-normal times I think our Prime Minister has been judged and found wanting. So do the authors of this book. We will see what the voters think in 2022.”

CRITICAL

Hence, when the book’s sub-title refers to “critical” reflections, the authors do mean “critical” in both senses of the term. It is more an evisceration than a book.

And this is, against the odds, what makes it fun to read.

The book is a collection of articles written about Morrison over the life of his leadership of the Liberal Party. Such articles have appeared in respected, sometimes Christian-linked, alt-media publications like The Good Sauce, The Epoch Times, The Spectator Australia, Quadrant, The Cauldron Pool, and The Australian. (Publishing anything overtly anti-Morrison is noteworthy for The Oz).

Clearly, then, the book is not a biography as such. This isn’t a problem, in view of the essential purpose of the book and the fact that many readers would find nothing more tedious than such a venture.

The authors arrange a series of quite short chapters to deal with a specific issue on which Morrison has acted or spoken.

Or, in far too many cases, not acted and not spoken. On most issues, the Prime Ministerial incumbent is found wanting.

The introduction is especially interesting.

In drawing upon the work of a disgruntled ex-Liberal, John Ruddick, the authors express surprise at two things in particular about Morrison.

One, he didn’t seem to be remotely interested in policy or politics in his youth. He lacked political ambition or interest of any sort before middle age.

Christine Wallace (a genderist critic) opined, in reviewing the Smethurst biography: “Morrison’s private and public sector record is revealed as strikingly vacuous. He also comes across as a bit of a Liberal Party entryist, using it as a platform for personal ascension rather than having real roots in it.

And two, he didn’t have any training in classical education, political science or the law.

CONTRAST

In both of these things, Morrison provides a sharp contrast to just about every other major Party leader Australia has ever had.

What does this suggest? That Morrison is a career chancer, totally non-ideological (in a bad way), and isn’t grounded with a passionate, long-held belief system or world view.

That he is, indeed, simply Scotty from elsewhere. Scotty, perhaps, from nowhere we can recognise.

Not that there is anything wrong with political outsiders. There is mounting evidence that being an “insider” is a big part of the problem of our current superficial, vacuous governance.

No, Morrison is a different sort of “outsider”.

To re-read Morrison’s contribution on just about every issue of importance to his electoral base is to be reminded of his catalogue of deficiencies, some of which – there are so many – we might have forgotten, and to be shocked afresh.

Whether it relates to his prevarications over his support for Tony Abbott in the 2015 leadership spill, especially the second and fatal one; his failure (as a proclaimed Christian) to support Christian principles in the abominable defenestration of Israel Folau; his sucking up to Victorian ogre Daniel Andrews; his weirdly awful treatment of the outstanding former CEO of Australia Post, Christine Holgate; his abandonment of any leadership role in safeguarding our Constitution during the alleged COVID “crisis”; his appalling creation of the National Cabinet; his languid consideration, then abandonment of, any serious effort to define and to defend religious freedom. The list continues.

TASTER

Yet, the authors are just warming up. These simply provide a taster.

These failings in core matters give rise to chapter headings like “With Friends Like ScoMo, Who Needs Enemies?”; “The Andrews Government’s Chief Enabler”; “The Prime Minister’s Failure to Uphold the Constitution”; “Morrison Urges Social Media Bosses to Practice More Censorship”; “Not Just Worse Than Doing Nothing, But the Wrong Thing”.

A quick look through the table of contents, then, suggests there are no prizes for guessing the direction of travel of this book.

Then there are all the telling ScoMo quotations, that (perhaps unintentionally on the Prime Minister’s part) reveal much about the man who leads the nation.

As do his strategic silences on issues upon which he should have been out there, using his prime ministerial bully pulpit to argue for what he knows, or at least should know, to be right.

The authors mention the awful arrest by VicPol thugs of Zoe Buhler for COVID thought crimes as one example of Morrison’s habit of being missing in action.

Another was Peter Ridd, treated appallingly for his climate honesty and scholarship by a university funded by the Morrison Government. Not to mention being shockingly treated by (some of) the courts.

But there have been many other examples of Morrison’s either lacklustre championing of core values or abject silence on the plight of those who he should have been defending.

It is almost as if the Prime Minister goes out of his way to offend those who he most needs to defend him in the community and on the hustings come election time.

But given he is willing, bizarrely, to take his own Party organisation to court on the very eve of the election, in order simply to circle the wagons of his factional allies, there is nothing in the area of policy or values that should surprise us about him.

STAGGERING

What does emerge from the book is someone who is pathologically driven to avoiding offending anyone, that is, anyone apart from his core base.

He doesn’t care remotely about offending them. But for anyone else, the lengths he will go to in order to avoid anyone thinking he isn’t “one of us” is staggering.

But I don’t think this is because he is a philosophical centrist. If that were the case, he might attract some sympathy.

No, it is abundantly clear from this book that he isn’t a centrist, but simply a man on the make, a chancer, a career slitherer who got lucky on several occasions, much to the nation’s cost.

Morrison is not Labor-lite, as those who wish to let him and his government off the hook so depict him.

He is Labor-heavy, but, we suspect, without even believing in the things that he has done that have wrought such damage.

Three of Morrison’s prominent failings are not covered in any detail by the authors. You can’t cover everything awful about ScoMo in a reasonably short book, after all, nor do you need to in order to make the point.

As legal scholars, Zimmermann and Loiacono generally prefer to keep to their own areas of interest and expertise, with a focus on rights, freedoms, discrimination, constitutional matters, and the like. There is plenty of material with which to be going on.

Other issues that warrant critical examination of Morrison could well include his office behaviour, his alleged bullying and his shouting demeanour. We can leave that in the capable hands of his internal Party critics (like Senator Fierravanti-Wells) and his political opponents.

Another is the Morrison Government’s house style of rorting. These caused one longstanding NSW Liberal MLC (Catherine Cusack) to resign in disgust. Who can forget the adventures of Bridget McKenzie, and what that said about the trashing of the erstwhile rock-solid principle of ministerial responsibility?

VANDALISM

A third area of policy disgrace has been the lurch towards the truly abominable economic vandalism that is net-zero emissions, a sop to the green-Left that will win Morrison no votes and lose him and his Government plenty.

He is attacked by the Left for doing too little on climate, and by the Right for doing too much.

He should, of course, be doing precisely nothing to appease members of the alarmist archipelago, and in the same vein, doing nothing about the climate non-problem.

Other than responding in a timely, systematic, sympathetic and focused manner to an actual climate (well, a weather) crisis like the Northern Rivers floods in NSW. He did not.

We could also talk about the ongoing and unaddressed crisis in aged care. Or Morrison’s weird political bromances with ghastly State leaders like the out-of-control McGowan and (of course) Andrews, in which national solidarity with crypto-fascists was placed way above the basic rights of citizens.

The size of the list of Morrison Government sins of commission and omission is both long and seriously impressive. The sheer breadth of the Government’s failures is astonishing.

No, this book is decidedly not a friendly critique. But it is an essential one of what the authors term a “Seinfeld Government” – a show about nothing, but without the laughs. Ouch.

It must give every reader and every Australian voter pause to consider – can I really reward this man with another term of government?

Indeed, the authors finish by saying: “It hasn’t achieved anything of significance in three terms that you would expect a centre-Right government worthy of the term to achieve. Why would it achieve anything in a fourth?”

I would go even further. This is not just a Government and a “Hollow Man” Prime Minister (the authors’ apt phrase) of non-achievement.

This Coalition has done immense, possibly irreparable harm to our economy, our rights, our freedoms, our communities, our social fabric, especially since March 2020.

WAGONS

One of the great recurring themes of the many COVID-sceptics and those opposed to vaccine mandates in recent times has been – those who perpetrated the COVID crimes must not be allowed to get away with it.

Those Liberal-friendlies now circling the wagons in order to keep Labor out must not be allowed to win this argument. It is our duty as citizens to take whatever actions we can to ensure punishment of the COVID villains. Nuremberg Two, if you will.

Voting out the governments involved is one of the very few practical and legal actions we can easily take.

George Christensen recently retired from the Parliament. Then he resigned from the LNP. Then he announced that he would not be voting for the Coalition come the election.

One thing he has said has resonance here. He said that the Liberal Party “lost its soul” when it decapitated Tony Abbott in 2015.

SOUL

Indeed. But perhaps it had already lost its soul and this is what enabled it to do what it did to Abbott.

Maybe the crushing of Abbott’s prime ministership was both effect and cause.

What an awful predicament we are in as the result of this coincidence of events. Morrison and the current incarnation of the Liberal Party may well deserve each other.

One minor quibble with the book. The authors quoted with some relish John Ruddick’s put down of Morrison’s degree in economic geography. My PhD was in economic geography…

This piece was originally published in the Australian political journal Politicom and is republished here with the kind permission of the author.

Paul Collits is an Australian freelance writer and independent researcher. He publishes widely across a number of Australia’s leading publications and has been one of the country’s single most cogent commentators throughout the Covid era. He has worked in government, industry and the university sector, and has taught at tertiary level in three different disciplines – politics, geography and planning and business studies. A collection of his writing published in A Sense of Place Magazine can be found here. He posts regularly at The Freedoms Project here.