By Paul Gregoire: Sydney Criminal Lawyers Blog

Released in June, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2023 outlines that the Australian use of the illegal drug cocaine is per capita the highest in the world, whilst Sydney has long been known as this nation’s capital of coke.

However, over the time since our country took out the UNODC cocaine use accolade in June, there has been a spate of killings on the Sydney streets in circumstances thought to be related to the trade in cocaine, which has seen drug kingpins executed, as well as others injured, including the innocent.

Indeed, Sydneysiders continue to consume cocaine at growing rates, despite our distance to its South American source leading to exorbitant prices, which only continue to rise, as well as the fact that much of it is of low quality, as it’s cut with numerous adulterants, prior to its on-the-street sale.

The 2021-22 NSW Crime Commission Annual Report outlines that the importation of illicit drugs is the primary driver of organised crime in this state, and, as it’s noted in the past, despite numerous annual drug seizures at the border, the local availability of imported illicit substances isn’t impacted.

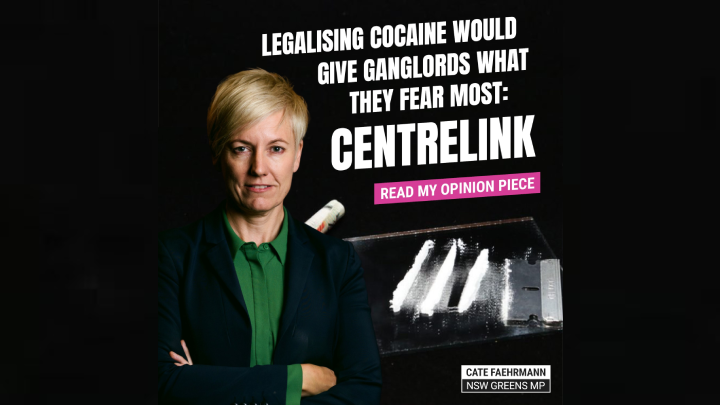

And following the latest street drug execution on 27 July, Greens MLC Cate Faehrmann has penned an opinion piece in SMH, calling on the Minns government to consider the one approach that will “drive organised drug gangs out of business overnight”, which is “legalisation”.

Crippling organised crime

“Recreational or not, when you make it illegal to possess something that people want, you’re going to have a black market on your hands,” said Faehrmann, whose been making this point about illicit substances since she re-entered NSW parliament in August 2018.

“The Australian Institute of Criminology says that organised crime costs Australia over $60 billion a year, much of which can be attributed to illegal drug activity and consequential activity like money laundering,” the NSW Greens drug law reform spokesperson added.

To further support her argument for legalising cocaine, Faehrmann pointed to a comment recently made to SMH by an unnamed NSW police source, who said, “These gangsters would be on Centrelink in six months if you legalised drugs”.

This comment reflects the growing community understanding, even within the force, that rather than reduce illicit drug use, prohibition increases it, while it also creates crime networks and unnecessarily criminalises those who use drugs, and that the safest source of drugs is a legal one.

“That black market is obviously of very high value to criminals,” Faehrmann further told Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

“If we legalised cocaine, making it safely available for recreational use, that black market will cease to exist almost immediately.”

Legalisation reduces harm

Cocaine isn’t the usual go-to illicit substance in the legalisation debate. And it’s the relationship of the drug to the recent violent shootings that have scarred this state’s community that has led the NSW Greens MLC to point out the huge harm reduction that legal cocaine would lead to.

“There are a couple of reasons why cocaine isn’t really mentioned,” Faehrmann said. “Part of the reason is that there’s greater sentiment around legalising cannabis, so until that gets legalised first, there isn’t too much optimism around a campaign for cocaine legalisation.”

So, a clean, affordable and legal supply of cocaine would definitely result in less criminal activity and violence on the streets, as well as make its use a lot safer.

“Another factor is that cocaine doesn’t really have a use in modern medicine, unlike cannabis and MDMA,” the Greens harm reduction spokesperson continued. “So, cocaine is sort of seen purely as a recreational drug, without the additional reasons to legalise it.”

But, as Faehrmann stressed, regardless of how cocaine is used, there’s a huge market for it here, and people are being “shot in broad daylight” in relation to it.

A global movement

Calls for an end to the war on drugs have only grown in strength over the last decade since the Global Commission on Drug Policy declared it to be a failure in its first report released in 2011, titled The War on Drugs.

The significance of this report, and the ten more that it’s produced in its wake, is that the Global Commission is comprised of former heads of state and renowned public figures. Indeed, in 2011, it included the former presidents of Mexico, Colombia and Brazil, as well as an ex-PM of Greece.

The report outlined that the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the foundational treaty of modern drug prohibition, as well as the official launch of its law enforcement arm, the war on drugs, in 1971 by then US president Richard Nixon, have resulted in the opposite of their stated aims.

The commission, which is today chaired by former NZ PM Helen Clark, outlined that prohibition has led to an increase in drug supply, the creation of huge international criminal networks, the increase in harms associated with drugs and the criminalisation of millions of otherwise law-abiding people.

We “encourage experimentation by governments with models of legal regulation of drugs to undermine the power of organised crime and safeguard the health and security of their citizens”, the commissioners wrote.

Dragging its feet

The NSW Minns government took office in March, after over a decade of Coalition rule that had seen community calls for the decriminalisation and legalisation of what are today illicit substances growing, whilst Liberal Nationals ministers responded with the slogan “just say no” to drugs.

But in line with shifting public attitudes, the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry into the Drug Ice and the NSW Inquest into the Death of Six Patrons of NSW Music Festivals both called for a different approach to drugs, including the decriminalisation of personal possession and use.

For its part, the Minns government has promised to put drug law reform on the agenda, but instead of acting on the advice of the two expert reports, NSW Labor has called for another drug summit at some point in the future, following in the footsteps of the successful 1999 NSW Drug Summit.

“Look, it’s unfortunate that we need a drug summit at all,” Faehrmann made clear. “All the experts are saying that we’ve got the insight we need for best practice drug law reform through” the inquiry and the inquest.

“Yet here we are being told that we need a drug summit,” the Greens member continued. But “at the same time, we can’t get an indication of when the summit will commence”.

Infinite Time or Time Delays

There’s a huge difference between the time of the last summit and the present though, as the ACT Labor Greens government has already legalised the personal possession and use of cannabis, it’s also implemented pill testing and it’s about to decriminalise the most popular illicit drugs in October.

“When it inevitably does commence,” Faehrmann said in conclusion, “I hope the drug summit looks to broader issues that weren’t recommended by the ice inquiry, like pill testing and legal regulation of cocaine.”