Aidan Coleman, Southern Cross University

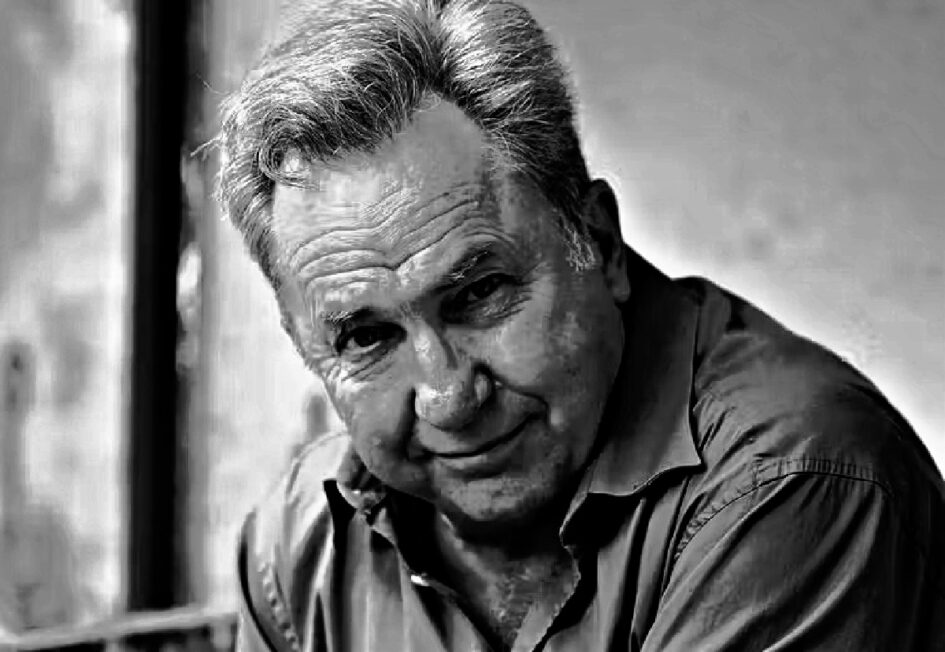

Perhaps more than any Australian poet of the 20th Century, John Tranter, who died last Friday at the age of 79, was guided by a relentless desire to experiment. His earliest admiration was for the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, and he soon discovered John Ashbery, who ultimately became his most important influence.

Tranter was dissatisfied with the Australian poetry scene he encountered in the mid-1960s. He rejected what he saw as a political and aesthetic conservatism, with its roots in an Anglo-Irish tradition and little sympathy for the French innovators of the 19th century or more recent developments in the United States.

The hoax poet Ern Malley was the only Australian influence Tranter credited.

Early work

The poems in Tranter’s first collection Parallax (1970) were short and often tentative in their disjunctions. His experiments were propelled further in Red Movie and Other Poems (1972), The Blast Area (1974), and The Alphabet Murders (1976).

These early collections show Tranter discarding conventional subject matter and a stable speaking voice for a purer realm of textual play:

when the new alphabet soup of the earth

is raised into a flag, the inevitable wind appears

with its own “sister to breath”.[…]

thoughts of silver oppress the lake

:such light

opening a way through.

In these poems, disjunctions are heightened and shifts in pronouns are intensified, as metaphors are bent and deranged. Tranter returns to the subjects of movies, drugs, fast cars and weaponry, but the nouns are employed for their textural grit and the atmosphere they generate more than for what they signify.

The work baffled those readers and critics attuned to more conventional models. It was claimed by some that the poems lacked emotional depth. But many reviewers, Martin Johnston among them, recognised something that was vital and new.

Crying in Early Infancy: 100 Sonnets (1977) was written concurrently with these collections. The sonnet form brought a greater sense of coherence, as it foregrounded the wit and an urbanity that was sometimes muted in Tranter’s earlier work.

Unlike the majority of his contemporaries, Tranter quickly gained acceptance. Two of his early books were published by Angus & Robertson, a mainstream publisher that had a validating role in Australia akin to Faber & Faber in the United Kingdom. This venerable publisher produced his Selected Poems (1982), before the poet had turned 40.

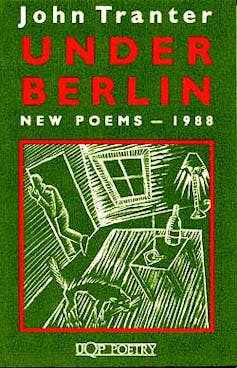

Tranter’s most celebrated work is Under Berlin (1988), which was published almost a decade after his previous single volume. Many of these poems exhibit a consistent tone and a stable voice. There are discernible themes, which likely contributed to its critical acclaim. The book was awarded both the Kenneth Slessor Prize and the Grace Leven Prize for Poetry.

The poems show Tranter to have absorbed and refined the influence of Ashbery in the relaxed and confident tone of their lines. Their subjects are various. Bucolic settings that draw on Tranter’s rural upbringing sit alongside urban and domestic poems.

Backyard revolves around the Australian institution of the barbeque, subtly subverting the mythologising of those Australian poets who would raise the event to the status of a sacrament. The subject of North Light is the suburban man in a moment of contemplation. Debbie and Co., which begins – “The council pool’s chockablock / with Greek kids shouting in Italian” – is a snapshot of disaffected 20-somethings hanging out at the local pool.

Glow-boys considers the lives of workers who clear up nuclear waste. The poem is edged with the anxiety of its time, ending with an image of the workers progeny: “asleep, dreaming fitfully”.

Late experimentation

Some of the poems in At the Florida (1992) continue with this perfected style, but Tranter’s desire for formal experimentation remained. The book ends with a series of haibun: 20 lines of poetry, followed by a stanza break and a prose paragraph. Some signal a return to disjunction and difficulty. The collection was accompanied by a verse novel, The Floor of Heaven (1992), written in a rough iambic pentameter.

Before the close of the 20th century, Tranter was experimenting with AI and generative technologies. Different Hands (1998) is presented as seven “computer-generated collaborations” based on pieces by different writers “shaken, stirred and transformed by the poet”.

Neuromancing Miss Stein, for example, blends and reconfigures text samples from Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and William Gibson’s Neuromancer. The results are interesting, but underwhelming in light of the strong work which precedes and follows it.

Tranter’s last two major publications, Starlight: 150 Poems (2010) and Heart Starter (2015), show a poet in late career drawing on the resources of language and technology, restlessly wrestling against any settled style.

These poems show Tranter experimenting with text-to-speech software and returning to the sonnet form. Also prominent among his late work is the “terminal”, a form Tranter may have invented, in which the poet borrows the end-words of a previous poem to write a wholly new text.

Among these, the most memorable is The Anaglyph, a long discursive poem of cumulative power, which uses the opening and closing words of each line of John Ashbery’s Clepsydra.

Influence

Tranter’s influence can be seen in the work of later Australian poets, but his role as an editor, anthologist and publisher, from the early 1970s until well into the 21st century had a more immediate effect on Australian poetry.

He was involved with a number of little magazines in the 1970s, including the one issue of Free Grass, which he wrote under a series of aliases in a single afternoon.

His journal, Transit, was as ephemeral as the title suggests, but he resurrected the name for his publishing venture, which produced a number of books by the likes of John Forbes, Gig Ryan, Susan Hampton and Martin Johnston.

For better or worse, the term “Generation of ’68” was defined by the publication of Tranter’s anthology The New Australian Poetry (1979). The book undoubtedly aided the careers of some poets, but came in for harsh criticism. The selection favoured writers from Sydney and Melbourne, and included a mere two women among its 24 contributors. Many of the names commonly associated with the group are missing. Ken Bolton and Pam Brown, in particular, are confounding omissions.

The Generation of ’68 label, which still persists, has revolutionary connotations, invoking as it does the student riots in Paris. But it also had the effect of freezing the movement in a particular moment. The “new” was already in the distant past by the time of the anthology’s publication.

Tranter took the opportunity to amend for many of these faults when he co-edited, with Philip Mead, the Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry (1991), which placed Ern Malley at the centre of the Australian canon, reproducing Malley’s oeuvre as it was originally published by Max Harris.

The anthology highlighted the achievements of many of Tranter’s close allies, but its representation of women was broader than any Australian anthology to date. It was also generous to poets Tranter found himself at odds with, such as James McAuley and Les Murray.

Tranter was employed as a broadcaster for the ABC on various arts programs and founded Books and Writing with Jane Garrett. He worked alongside Martin Johnston at SBS – and after his friend’s death – compiled Johnston’s Selected Poems and Prose (1993).

Unsurprisingly, Tranter was at the forefront of the digital revolution. He was the founder of the now defunct Australian Poetry Library, which gave an international audience access to thousands of Australian poems, and he co-founded the Journal of Poetics Research.

In 1997, he established Jacket. This international online journal, which is still running as Jacket 2, is now based at the University of Pennsylvania. It continues to be a premier journal for contemporary experimental poetry.

Energy and invention remained hallmarks of Tranter’s life and work until the end.

Aidan Coleman, Senior Lecturer, English and Creative Writing, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.