Photography by Dean Sewell

Photography by Dean Sewell

The Carlisle Hotel in the back streets of Newtown in Sydney’s inner-west is one of the few places left in Sydney where the wowsers have not won; an old-fashioned pub in an increasingly strictured, shuttered country.

Hotels and beer gardens across Australia are now largely empty, barren places, the victim of grotesque over-regulation and over-policing, and an increasingly devastated economy. People just don’t have the money anymore.

The only people who seem to think the Australian economy is doing well are conservative politicians, paid many times the average wage, all of them desperately peddling the myth that they are good economic managers.

No, they are not.

Most everybody else knows the truth: the economy is tanking.

I came to know the Carlisle when for a while I rented the attic room in the big white house opposite, known to many of the locals as Poofter Palace after the charming grandiosity of the then owner, former opera singer Peter Binning.

In a very different part of town, The Big White House was also the name for the old Home for Incurables, a place which as a working journalist I had written a number of stories about. That, too, seemed appropriate, but enough of all that.

In this troubled, confused period of life I had come to rest in this little neck of the woods, and was determined to make my own village, to start anew.

And I loved the Carlisle.

There no bartender quoted Responsible Service of Alcohol legislation at any customer who dared to have more than two schooners in an afternoon.

Nor did they refuse to serve shots of tequila, bourbon or whisky, as so many other bars now do, in an increasing infantilisation of the population.

And nor were people refused service if they looked slightly dishevelled or hung over in the mornings, as now happens in so many other hotels, the dwindling remnants of freer times.

On the blackboard at the Carlisle were chalked the words:

Fill with mingled cream and amber,

I will drain that glass again.

Such hilarious visions clamber

Through the chamber of my brain —

Quaintest thoughts — queerest fancies

Come to life and fade away;

What care I how time advances?

I am drinking ale today.

The lines were said to have been penned by master of the macabre Edgar Allan Poe while drinking in a tavern in Lowell, Massachusetts and passed on to literary scholar Thomas Mabbott by a barman. While the authenticity of the quote has been disputed, it really didn’t matter, it was that sort of hotel.

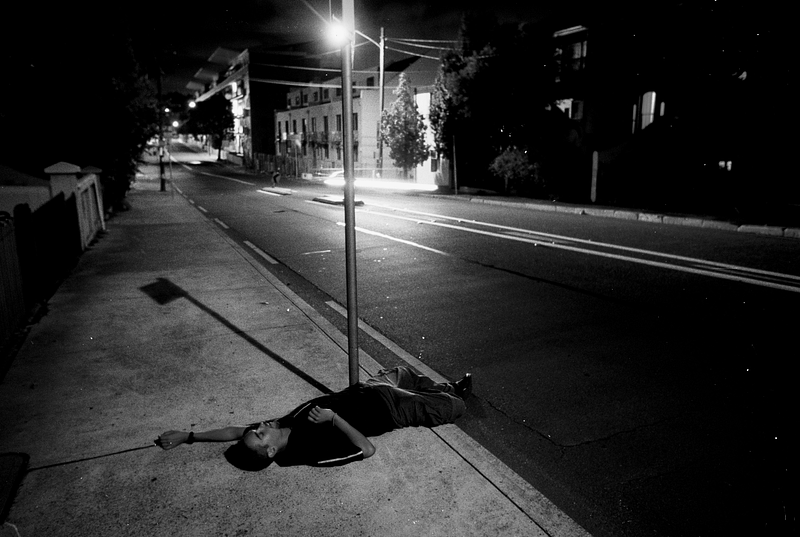

Poe, who struggled with alcohol all his life, died aged 40 after being found lying in the gutter outside a polling booth on election day in clothes not his own, delirious, unable to move and in great distress.

Theories on the mysterious death of the inventor of the mystery story suggest he was bashed by “ruffians” or was the victim of a voting fraud scheme, where strangers were abducted and forced to vote multiple times. In those days each voter was given a shot of alcohol after voting as a reward, and Poe may well have been suffering from alcoholic poisoning.

That his words should grace the Carlisle more than 160 years after his death was more than apposite.

Workers gathered at the Carlisle from 4pm to take advantage of Happy Hour.

Once they might have cared to exchange their prejudices on all manner of things: the idiocy of politicians, the bastardry of their bosses, the latest piece of bureaucratic inanity or politically correct absurdity. Now they had learned to keep their views to themselves, and talked of little but football, while the rundown poseurs at the other end of the bar sat in self-affirming clutches and exchanged their spiteful, fruitless gossip.

Dogs sat on barstools. Crazies muttered.

The Carlisle was, at least for for me, the archetypal bar:

As J. R. Moehringer wrote in his splendid paen The Tender Bar:

We went there for everything we needed. We went there when thirsty, of course, and when hungry, and when dead tired. We went there when happy, to celebrate, and when sad, to sulk. We went there after weddings and funerals, for something to settle our nerves, and always for a shot of courage just before. We went there when we didn’t know what we needed, hoping someone might tell us. We went there when looking for love, or sex, or trouble, or for someone who had gone missing, because sooner or later everyone turned up there. Most of all we went there when we needed to be found.

Everyone had their view; and for the many university students in that part of the inner-city, those views were acquired through the orthodox left propaganda of the national broadcaster. They could tell themselves they were progressives, their friends would nod in agreement and they slept peacefully at night. They were good people.

As for the tradies and other workers who also frequented the hotel, if their views were out of sync with the prevailing fashions, or with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, most had learnt it was easier to say nothing at all for fear of being labelled misogynist, racist, sexist, homophobic, Islamophobic, ignorant and uncaring.

In an inflamed state of mind, it was easy to recall those Biblical words:

Jesus answered, “I have shown you many good works from the Father. For which of these do you stone Me?”

“We are not stoning You for any good work,” said the Jews, “but for blasphemy, because You, who are a man, declare Yourself to be God.”

Jesus replied, “Is it not written in your Law: ‘I have said you are gods’?”

These Gods sat on their bar stools along the length of the old fashioned bar, wreathed their prejudices ever closer to themselves and talked of little else but football. In truth, they were not welcoming. They did not heed Muhammad’s admonition: “Be kind to the traveller, courteous to the stranger.”

That evening Glen, who was not, as I was repeatedly warned, who he said he was, came to dinner, which with a retired opera singer in charge were always grand affairs.

“Do you believe in empaths?” Glen asked.

“Is it even possible?” his girlfriend asked.

“Sure,” I replied. “The full potential of the human brain is rarely explored. A military trained empath is in and out of your head in a second, an untrained one senses images, emotions, intent, loud thoughts, but that is all. They can cause a lot of problems. They leak all over the place. They are often troubled individuals. They have difficulty making sense of everything around them. They don’t understand their condition. They don’t understand why nobody else hears what they hear.”

As if by way of explanation. As if, in the accelerating crisis by which they were now gripped any of these gifts would be enough to save them.

There were always multiple betrayals. If you are vulnerable, people attack. Humans did not become the top predators on Earth by being nice.

Later in the garden Glen, aware of the abusive and intrusive surveillance I had endured ever since writing a book called Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost, began recounting various experiences; whispering campaigns, a throbbing echo just out of sight.

Came a spiel about targeted individuals, synchronicity, mimicking, gossiping, the treacherous undermining or destruction of the reputation or credibility of those who dared to go against the government line, the voices just out of reach, the many many things that didn’t make sense and made the targeted individual doubt their own sanity.

“That’s happened to me,” I said, recognising explicitly many of the techniques Glen was recounting.

“They’re called Psyops, or Psychological Operations,” he said. “There’s a whole theory behind it. Look it up. There’s plenty of material around. You become conditioned. They can trigger a fright-flight response just by a sound.

“And if the person has had any problems, say with a particular drug, they will find themselves suddenly being offered it wherever they go.”

I asked: “And so, the person is so disturbed, so disoriented, he thinks he’s going mad, and either retreats or commits suicide?”

“Precisely.”

“Why don’t they just kill the person in question?”

“Because that would look suspicious.”

This is an extract from the book Hideout in the Apocalypse.

All images are copyright to Dean Sewell. He can be contacted for assignment or reuse of images through the photographer collective Oculi or his Facebook page.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS