Laura McKemmish, Albert Fahrenbach and Martin Van Kranendonk, University of NSW, Sydney

The search for habitable conditions beyond Earth has just become more interesting with the discovery of biologically available phosphorus from one of Saturn’s moons. Phosphorus is the most elusive of the six crucial elements needed for life.

In research published today in Nature, data from the Cassini spacecraft were used to find phosphorus compounds called phosphates in Saturn’s E ring – one of the fainter outer rings of the planet.

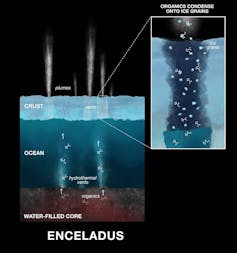

These compounds likely came from the ice volcano (cryovolcano) plumes from the sub-surface liquid water ocean on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

A famous moon

Enceladus seemed like a typical moon of Saturn until the Cassini spacecraft came to take a closer look. Arriving at Saturn in 2005, Cassini has been making discovery after discovery that have catapulted Enceladus to one of the top places to look for life beyond Earth.

In particular, we learned Enceladus has a liquid water ocean beneath its icy surface, heated by gravitational tidal forcing – the kind of forcing that produces ocean tides on Earth.

This environment is tantalisingly similar to the hydrothermal vents thought by some to be the place where life may have originated on Earth. Such vents certainly host life on Earth today.

Most life on Earth ultimately relies on photosynthesis – generating energy from sunlight. Meanwhile, the ultimate energy source for any life on Enceladus would be the gravity of Saturn producing tides far stronger than the Moon produces on Earth, allowing a liquid water ocean despite the very cold -200℃ ice crust surface.

Easy sampling

The Enceladus plumes have been called a “gimme” for efforts to sample the oceans of alien worlds. One wouldn’t need to land to collect a sample, nor to then launch to return it for analysis.

An obvious approach to sampling an ice volcano is to simply fly through it. However, this is difficult because the speed at which a space probe would encounter the plume would likely kill most organics.

Instead, the easiest approach is to examine the accumulation of ejected material from Enceladus in Saturn’s E ring, which is what the team did in this latest study.

Using this approach, researchers have previously discovered complex organic molecules coming from Enceladus. These findings confirmed that the watery environment on Enceladus supports complex chemistry involving nitrogen and oxygen.

However, until now we didn’t know about the availability of phosphorus on Enceladus; in many environments this element is locked in rocks.

A crucial element

The discovery of phosphates in Saturn’s E ring suggests phosphates could be available within the oceans of Enceladus at a concentration 100 times higher than in Earth’s oceans.

Phosphorus is crucial for life as we know it, partly because it is a key building block of DNA and RNA, molecules essential to all life on Earth. Phosphate is also vital for a number of other metabolic processes in all life.

Many of the essential components necessary for the emergence of life as we know it have thus been discovered on Enceladus. This puts it at or near the top of lists of places to search for life beyond Earth in our Solar System.

Nevertheless, this discovery is only the start of the story. For phosphate to form bonds with carbon – this type of bond is found in the backbone of DNA – we need specialised chemistry that’s very dependent on the environment.

We’ll need further study of the chemistry in and under the crust of Enceladus. But a future detection of organic phosphate compounds would be particularly interesting for the potential for life in the moon’s oceans.

No ‘smoking gun’

This research is reminiscent of the reported detection of phosphine on Venus in September 2020, which was cast into doubt by later evidence.

However, the detection method is quite different. On Venus the presence of phosphine was proposed by observing the atmosphere from Earth. The phosphates in this study were detected using an instrument orbiting Saturn called a mass spectrometer, which measured the mass of individual compounds found in the ice of the E ring.

To verify the analysis, the authors created a water solution on Earth very similar to the predicted Enceladus ocean.

That said, both detection methods carry a risk of misidentification, where a different molecule that’s not phosphine is actually responsible for the result.

It would be great to have a “smoking gun” for life beyond Earth, but realistically it will instead be a trickle of evidence that grows as we discover more about these environments.

The study published today is one more piece of evidence supporting the fact that Enceladus may be a great location in our search for extraterrestrial life.

Acknowledgements: We thank Prof Steve Benner from The Foundation For Applied Molecular Evolution for his insight and contributions to this article.

Laura McKemmish, Lecturer, UNSW Sydney; Albert Fahrenbach, Senior Lecturer, UNSW Sydney, and Martin Van Kranendonk, Professor and Director of the Australian Centre for Astrobiology, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.