From Maria Popova: The Marginalian.

A Sense of Place Magazine is an unabashed fan of Maria Popova’s celebrated blog The Marginalian, to our mind the best and most easily accessible literary journal in the world. We cannot recommend it more highly.

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian born New York based polymath who has, it seems, read everything worth reading so that the rest of us mere mortals don’t have to. Not just supremely intelligent, she has an uncanny eye for beauty combined with a deeply felt sense of what makes us human.

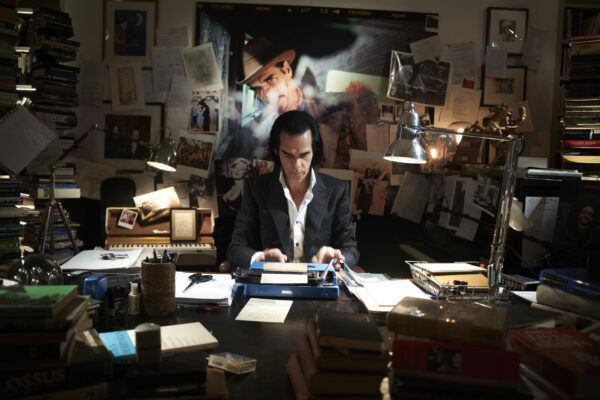

In this piece she combines with another of our era’s most luminous creative spirits, Nick Cave, on his new book Faith, Hope and Carnage.

In praise of “the necessary and urgent need to love life and one another, despite the casual cruelty of the world.”

The world reveals itself through our engagement with it — a truth as true in the “It for Bit” sense of physics as it in the Dzogchen sense of Tibetan Buddhism.

It is the fundamental truth of our human experience.

All cynicism is a denial of it.

All hope is a tribute to it.

This awareness pulsates throughout Faith, Hope and Carnage (public library) — Nick Cave’s yearlong conversation with journalist turned friend Seán O’Hagan.

Two decades after Rebecca Solnit’s epochal Hope in the Dark, with its lucid and luminous case for our grounds against despair, Cave — who has long championed the generative value of hope — reflects:

I have no time for cynicism. It feels hugely misplaced at this time.

[…]

I remain cautiously optimistic. I think if we can move beyond the anxiety and dread and despair, there is a promise of something shifting not just culturally, but spiritually, too. I feel that potential in the air, or maybe a sort of subterranean undertow of concern and connectivity, a radical and collective move towards a more empathetic and enhanced existence… It does seem possible — even against the criminal incompetence of our governments, the planet’s ailing health, the divisiveness that exists everywhere, the shocking lack of mercy and forgiveness, where so many people seem to harbour such an irreparable animosity towards the world and each other — even still, I have hope. Collective grief can bring extraordinary change, a kind of conversion of the spirit, and with it a great opportunity. We can seize this opportunity, or we can squander it and let it pass us by. I hope it is the former. I feel there is a readiness for that, despite what we are led to believe.

Having long reckoned with the relationship between cynicism and hope, I often say that cynics — who are the people most deserving of our pity — are just brokenhearted optimists. There is both a lovely confluence and a lovely inversion of these ideas in Nick Cave’s assertion that “hope is optimism with a broken heart,” which seems to me more like an aphoristic spear nobly thrown at our perpetual tangle of semantics in trying to differentiate between optimism and hope than a genuine and useful definition.

But, of course, we each arrive at these notions so trapped in our own frames of reference, so saturated with our subjective experience, that no two portraits of a mental state or emotional orientation could ever possibly be precisely alike.

What is certain is that no matter what we call this openhearted yearning for betterment, pulsating beneath it is the infinite vulnerability of remaining unmet — all daring is forever haunted by the spectre of crushing disappointment, and there is nothing more daring than a reach from the real to the ideal.

And yet this yearning springs from our most fundamental nature. Living with it and living up to it is the highest homage we can pay, and must pay, to the unbidden gift of life.

With an eye to “the necessary and urgent need to love life and one another, despite the casual cruelty of the world,” Cave observes:

In a way my work has become an explicit rejection of cynicism and negativity. I simply have no time for it. I mean that quite literally, and from a personal perspective. No time for censure or relentless condemnation. No time for the whole cycle of perpetual blame. Others can do that sort of thing. I haven’t the stomach for it, or the time.

Life is too damn short, in my opinion, not to be awed.

NICK CAVE

In my own experience, nothing seeds cynicism more readily than the withholding of forgiveness — forgiveness of others, of the world, of Father Chance and Mother Circumstance; above all, of oneself. Self-forgiveness is indeed the most potent antidote to cynicism I know.

Cave shines a sidewise gleam on the same intimation. Half a century after the great humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm made his countercultural case for why self-love is the foundation of a sane society, he turns to art as the supreme instrument of self-forgiveness:

We all have regrets and most of us know that those regrets, as excruciating as they can be, are the things that help us lead improved lives. Or, rather, there are certain regrets that, as they emerge, can accompany us on the incremental bettering of our lives. Regrets are forever floating to the surface… They require our attention. You have to do something with them. One way is to seek forgiveness by making what might be called living amends, by using whatever gifts you may have in order to help rehabilitate the world.

For many of us, our creative contribution — our art, to use the term in Baldwin’s broadest sense — is the gift we offer to rehabilitate the world and, in the process, rehabilitate ourselves. Cave reflects on his own experience of making music while living with the incomprehensible loss of his teenage son and its attendant vortex of self-blame:

Art does have the ability to save us, in so many different ways. It can act as a point of salvation, because it has the potential to put beauty back into the world. And that in itself is a way of making amends, of reconciling us with the world. Art has the power to redress the balance of things, of our wrongs, of our sins… By “sins,” I mean those acts that are an offence to God or, if you would prefer, the “good in us” — that live within us, and that if we pay them no heed, harden and become part of our character. They are forms of suffering that can weigh us down terribly and separate us from the world. I have found that the goodness of the work can go some way towards mitigating them.

What emerges is the sense that the end of suffering begins with self-forgiveness, which in some elemental sense is the aim and end of all art:

Anyone who says they don’t have any regrets is simply living an unconsidered life. Not only that, but by doing so they are denying themselves the obvious benefits of self-forgiveness. Though, of course, the hardest thing of all is to forgive oneself… One sure path to self-forgiveness is to arrive at a place where you can see that your day-to-day actions are making the world a measurably better place, rather than a worse place — that is pretty simple stuff, available to all — and to arrive at this place with a certain amount of humility.

Complement these fragments from the wholly soul-broadening Faith, Hope and Carnage with Anne Lamott on forgiveness, self-forgiveness, and the relationship between brokenness and joy, then revisit Nick Cave on songwriting and the mystery of the unconscious, creativity and the myth of originality, and awe in the age of algorithms.

OTHER NICK CAVE STORIES IN A SENSE OF PLACE MAGAZINE