Extract from Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost.

To begin at one kind of beginning. As one of the country’s longest suffering general news reporters, having spent almost a quarter of a century as a staff member on some of the nation’s most difficult, treacherous news floors, and more than 40 years as a journalist of one kind or another, Alex had covered many an ANZAC memorial service; standing with other reporters pad in hand in the predawn darkness of Martin Place or mingling, with pad in hand, among the dignitaries.

Alex had never hesitated to ignore all the usual bounds of official protocol or the roped off sections in which the media were supposed to contain themselves, and would sometimes find himself standing next to the State Premier of the day, the State Governor, past and present Prime Ministers, the Chief of the Armed Forces.

He regarded it as an essential tenet of journalism, talk to anyone, high or low.

One such story, written for The Australian newspaper in 2007, read: “Despite torrential downpours, thousands of people were crowded into Martin Place for 4am for the dawn service; many families brought their wide-eyed children. Amongst the crowd a were few elderly diggers from the Second World War, fewer in number year by year.”

Ronald Hanton, 87, said he wouldn’t wish war on anyone: “I am one of the only survivors. Life is a wonderful experience, but I wouldn’t want to send someone into the same situation I experienced.”

Despite bouts of heavy rain, the atmosphere was hushed as state governor Marie Bashir read the dedication: “We who are gathered here think of those who went out to the battlefields of all wars, but did not return. We feel them near us in spirit.”

Official guests who laid wreaths at the Cenotaph included NSW Premier Morris Iemma, state opposition leader Barry O’Farrell, Federal Environment Minister Malcolm Turnbull representing the Prime Minister John Howard and Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore.

Eight years on Iemma had disappeared into the blighted history books of the state’s Labor Party, O’Farrell had been and gone as State Premier, vanishing in scandal into the ignominy he deserved, Turnbull was cooling his heels as the nation’s Communications Minister while plotting another tilt at the leadership; and John Howard had become only the second Prime Minister ever to lose his own seat at an election.

Only Clover Moore remained in the same role, hated by the city’s business people, an enduring pestilence on the city; the person who, as far as Alex was concerned, had singularly, more than any other person in the city’s history, destroyed the raffish charm and bohemian character of Sydney, bringing, through grotesque levels of regulation and environmental zeal, its once once vibrant inner-city life to a standstill.

Chaplain Murray Lund led prayers for peace around the world: “Raise up those who have

courage and vision to work for a new world where children can grow up in peace and

freedom.”

As rain poured down a lone bugler played the last post, followed by a minute’s silence. Naval Commander of Australia, Rear Admiral Davyd Thomas, urged the crowd to remember the 3,500 Australian servicemen and women serving overseas and said the Anzac tradition continued through them: “Many of them were in harm’s way this morning. Their service is still selfless, the mateship is as deep, the teamwork just as

vital.”

Like so many of his fellow countrymen caught up in another American quagmire and still suffering the consequences 40 years later, Ross Mangano, 67, who lost a leg in the Vietnam War, recalled a priest in an army field hospital trying to read him his last rites.

“I shouted at him that I had never seen snow, I wasn’t going to die,” he recalled. “My platoon sergeant died in Vietnam, and I march for him and for all my mates who can’t march. You can’t go to war and not lose any soldiers. I am very proud to be Australian.”

As part of those ceremonies, eight long years before, a special award was given to Wall Scott-Smith, the chief custodian of the Cenotaph for the previous 60 years. He had never missed a dawn service in all that time.

“The crowds started increasing about seven years ago,” he said as Alex had struggled to take down the words, in his own mix of shorthand and personal hieroglyphics, in the middle of the jam packed crowd, in the pouring rain.

“At first it was teenagers, now it is mom, dad and the kids. The Dawn Service is very important, it means so much.”

Many families had taken their children. Eight-year-old Claudia Cirillo from Manly, a beach suburb on the other side of the harbour, said of the service: “It might make little kids sad about the people who died in the war, but it is still important they come.”

Her mother Janette Cirillo said it was important to bring her children. “Anzac Day and the Dawn Service is part of our Australian heritage,” she had told him.

Scott Stanford, 37, dressed in full army regalia, said his great uncle Roy Stanford had been killed at Gallipoli: “I march so it is not forgotten about,” he said. “I bring my young son, who is eight, with me every year. It is not about glorifying war, it is about ensuring it never happens again.”

It would happen again.

After decades in journalism, there weren’t too many things Alex hadn’t written a story about.

He had also written a story about the world’s last survivor of the Gallipoli campaign. Several years before the old man’s death Alex had been obliged to do a phone interview with Alec Campbell, on the occasion when Alec, due to having outlived everybody else, had become the last surviving Gallipoli veteran.

Most people, particularly the elderly, are pretty chuffed if the national newspaper rings them up over one honour or another. Not Alec.

Given the assignment by the Chief of Staff, Alex went about his duties. Unlike so many others, mortgage rates, interest rates, property prices, some dismal little demographic trend, something one of the editors had heard at a dinner party the previous evening, at least interviewing the oldest living survivor of the Gallipoli massacre had been a story worth doing.

In the first instance Alec’s protective wife said she wasn’t sure if he would feel like talking. An old carpenter, he was way down the backyard somewhere banging away at things, and didn’t usually like to come to the phone.

Alec took his time, that was for sure. Alex hung on the phone for a good 15 minutes or more. Alec wasn’t honoured, he was grumpy that he had been disturbed doing whatever it was he had been doing, banging away at things as his wife put it.

Alex found him, well, taciturn; very unimpressed by politicians, proud of his union background, “up the bosses”, and contemptuous of the military commanders who had sent his comrades to their deaths in their thousands, the terrible slaughter he had witnessed first hand.

And, as had once been the traditional Australian way, utterly contemptuous of

politicians.

He hadn’t wanted to march on Anzac Day because he didn’t want to glorify a lie: that war was a noble enterprise.

Alec Campbell had never sought fame for himself, never attended Anzac ceremonies until very late in life, thought the glorification of war was a complete crock and almost never spoke about his experiences at Gallipoli. There were better, more positive things in life.

He had worked many different jobs, as a stockman, carpenter, railway carriage builder and in his later years as a researcher and historian. He gained an economics degree at the age of 50. His love of life extended to an enthusiasm for sailing, and he circumnavigated Tasmania.

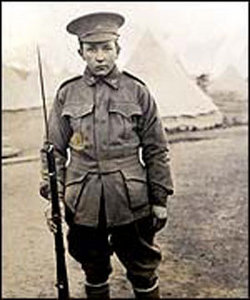

Like so many other young men deluded into thinking he was joining for a great cause

and for an adventure worth having, he lied about his age to join up. He had been 16

when the horrific bloodbath that was Gallipoli occurred.

It was the boundlessly cheerful and the optimistic, as Alex had observed from

interviewing countless people of all ages, who survived into old age; who did not let the

injustices of life eat into their souls and kill them early. Campbell died in Tasmania at

the age of 103. He was survived by nine children, 30 grandchildren and 32 great

grandchildren.

The story Alex would subsequently write in May of 2002 on the occasion of Campbell’s

death was headlined “Tributes and praise pour in for an ordinary hero.”

Then Prime Minister John Howard’s media office had done a fine old job polishing up the

Anzac myth for public consumption. Howard was the first cab off the rank to praise Alec

Campbell: “On behalf of the nation I honour his life. Alec Campbell was typical of a

generation of Australians who, through their sacrifice, bravery and decency, created a

legacy that has resonated through subsequent decades and generations.

“All Australians will forever be in debt to the Anzacs, not only for what they did for us

but for the legend, for the tradition, for the stoicism under fire, sense of mateship and

all those other great ideals that, increasingly, young Australians see as part of their

inheritance.

“The wonderful thing is that the spirit and the tradition is growing stronger as the years

go by. It must have been a source of enormous comfort and reassurance and pride for

somebody like Alec Campbell in his later years to see the warm embrace of Anzac by

the young people of today as they walk the cliffs of Gallipoli.”

Bullshit.

On his deathbed Campbell pleaded: “For God’s sake, don’t glorify Gallipoli — it was a

terrible fiasco, a total failure and best forgotten.”

On the same day as the pre-Anzac Day threats, the 20th of April, 2015, Tony Abbott

officially bid farewell to 330 troops deployed to Iraq at the army barracks in Brisbane. The

ceremonies took place at the Gallipoli Barracks at Brisbane’s Enoggera Defence Base.

The troops were in addition to 200 Special Forces soldiers and 400 personnel already involved in the air mission against Islamic State. Australia had first joined the international effort to defeat IS militants in September after a direct request from US President Barack Obama. The contribution included six F/A18 fighter jets, a surveillance aircraft and a refueler.

The Prime Minister denied the provision of extra personnel was mission creep, claiming it was a continuation of “successful execution of the original mission.”

The troops were embarking on a two year mission, with most put to work training Iraqi soldiers. Defence officials asked the media not to identify the troops being deployed or their family members as a security precaution.

“The enemy we are facing has shown they are quite sophisticated,” Colonel Matthew Galton said. “They have been able to exploit things like social media so we are just taking prudent precautions for the safety of the troops, but more so for the safety of

their families back home.”

Abbott told reporters: “Our build partner capacity mission is all about trying to ensure that the legitimate government of Iraq has a trained and disciplined and capable force that understands the rules of armed conflict at its disposal to retake … the territory which is currently under the control of the death cult,”

Abbott told reporters. “Although Australian personnel will deploy to the building partner capacity mission in a non-combat role, they are fully aware that Iraq is a complex and dangerous environment in which to operate. Australian soldiers are among the finest in the world. We wish them all the best as they begin their mission and, importantly, we wish them a safe return to their families and friends.”

Addressing the troops Abbott said it was fitting on the eve of the centenary of Anzac that this was yet again a partnership between Australia and New Zealand.

“Good luck, may God bless you, and we look forward to welcoming you back after your mission is accomplished. You are going abroad to a faraway country, to uphold our interests and our values, to keep us safe. You go abroad to support us.”

The rhetoric of the Australian government was hyperbolic.

To his critics the Prime Minister was imperilling the lives of the military men and women with whom he claimed to have so much empathy with, involving the nation’s taxpayers in a conflict the country could not win, and taking morally indefensible action in a far off religious war, thereby inflaming local Muslim sentiment and bringing the conflict straight on to the streets and into the homes of ordinary citizens.

Within the month those same soldiers Abbott bid farewell to with such ballyhoo were camped perilously close to Islamic State, the massacres even more frequent, the security situation in Western countries increasingly perilous.

Australia, and Western, military intervention in Iraq had a long, expensive and

disastrous history.

Why would this time be any different?

It was not just the Muslims who criticized Australia’s involvement in the Iraq debacle. As Tom Switzer, Alex’s former colleague at The Australian turned political commentator and host of Between the Lines for the ABC’s Radio National, a once staunch supporter of Tony Abbott, wrote: “It pains me to say it, but Abbott has learned nothing about Iraq. He’s taken the Islamic State’s bait.”

Feature Image: Alex Ellinghausen. Courtesy The Canberra Times.

THE SERIES OF BOOKS ON CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN HISTORY BEGINNING IN 2015