The Great City: Extract from Dark Dark Policing by John Stapleton.

From Malcolm Turnbull’s first day as Prime Minister in 2015, the bombings on Iraq increased.

That is, he was responsible for killing more Muslims than any other Prime Minister in Australian history.

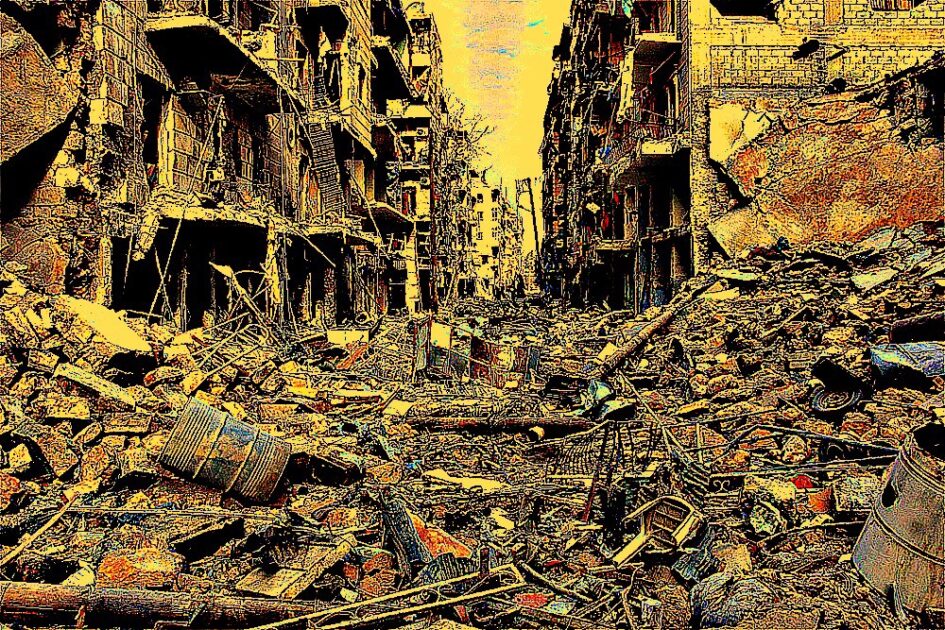

For years putrid skeletons were being dug out of the rubble.

Lovers, sons and daughters, soldiers old and young, men and women, children.

Most of all, believers in an Abrahamic god, Allah.

On both sides of the conflict they died in their thousands for their beliefs; in a modern day Crusader War which, like its predecessor, would echo down the centuries. All for a soldier’s wage: the simple, urgent need to support their families in the collapsed economy of Iraq.

As columnist Nicolas Stuart wrote in The Canberra Times: “I can still smell the filth, the lingering odour of death (think vomit plus defecation) that seeped up from under fallen masonry blocking the street. I can still see, in the houses, the scattered detritus of clothes and baby toys, the remains of lives torn apart by horror.

“No glory there, watching Iraqi people dying senselessly while our planes flew overhead.

“None, either, amongst the confusion of militias, each attempting to rule their own tiny patch of land according to the one true faith, whichever it happened to be at that particular moment of time; Shia or Sunni, Orthodox or Catholic, animist, nationalist or, when all else failed, simply a lust for power and money.”

Australian bombs helped make those corpses.

The ill-informed general public, betrayed both by the nation’s politicians and a heavily dumbed down media, thought about these deaths for not one second.

Certainly not the editors at the war mongering Murdoch rags; nor the national broadcaster, which could not claw itself away from gay marriage and climate change long enough to notice thousands of bodies rotting in the rubble of some far off place.

Even when Australian taxpayers had been ripped off for billions to contribute to this massive military debacle.

In a thunderclap of seismic proportions, the psychic echoes of a blood drenched conflict could be heard across the world. By anyone who cared to listen.

Former Prime Minister, the Jesuit trained Tony Abbott reliving the Crusades, was responsible for dropping 669 bombs on Iraq and Syria between September, 2014, when he announced he was taking Australia back into the Iraq War, and September 2015, when he was turfed from office.

No amount of security theatre or military posturing would save his dismal prime-ministership.

Ditto his successor.

The number of bomb drops began to increase immediately after Malcolm Turnbull seized power. Despite requests, no explanation was forthcoming from either the Prime Minister’s office or the Defence Department.

On gaining office in Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced his country would cease aerial bombardment.

No such humanitarian commitment came from Australia’s Prime Minister.

The bombs were estimated to range in size between 225 and 2000 lbs with a blast radius which could take out a city block.

By April of 2017 Turnbull had been responsible for dropping 1256 bombs.

In May of that year the bombing increased still further, with 119 bomb drops on Iraq, a further 106 bombs in June and 104 in July.

Dodging around legal definitions of war crimes could not hide the truth: Their actions were profoundly irresponsible; and those who were silent complicit in the outrage.

By the end of the year, the claim was that Islamic State had been defeated. Others, better informed, argued that the profound slaughter and martyrdom of its followers, courtesy of American and Australian bombs, was in itself a jihad trap.

Experts warned that Islamic State, far from being defeated, had created a major jihad spectacle in order to drive recruitment.

For this ludicrous level of strategic incompetence someone had to go to work in a factory and pay their taxes.

While the Prime Minister grinned and gripped his way through another insincere day.

Military analysts warned that far from the media coverage’s cartoon simplicity of good versus evil, the brutal nature of the Mosul occupation and the carpet bombing of so much of the Middle East was counterproductive, fuelling jihad sentiment worldwide.

Australian politicians paid no heed.

And wasted billions of dollars, only to make a difficult situation worse while the cultural legacy of Islamic State, including its thousands of videos and often powerful propaganda, would live on for generations.

Old Alex had been obsessed with the fall of Mosul long before its actual collapse, following the story for months.

It was a story which should have been staining the soul of the West, and the conscience of Australian citizens, if they had not all been trapped in a zombie zone of television soaps or raucous conviviality, looking everywhere but at the face of history.

Overlapping the site of Nineveh, once the largest, most populous and advanced city in the world, “the great city” as the Bible called it, the pulverising of Mosul and the massacre of its citizens held echoes from the past. The consequences of these 21st Century slaughters would transmit down future centuries. The prophetic methodology.

There was clearly, even viewed from the other side of the world in the heavily censored environment that was Australia, an occult aspect to it all.

The creation myths of the Assyrian empire, existing as early as the 25th Century BC and of which Nineveh was a major capital, saw the universe beginning in war. This was a cosmology echoed by Islamic State, as reporter James Verini recounted in his stunning book They Will Have To Die Now: Mosul and the Fall of the Caliphate:

“Existence began in war and through war it was perpetuated. Theirs was a creatio continua, and it was the responsibility of the Assyrian king to carry on the work of creation, to perpetuate the order the gods had introduced at time’s beginning.

“He did this through combat. It was official explanation and sacred rite. It was the means by which he communicated with the divine, connecting reality to myth, present to past, god to man. To the Assyrians, in other words, all war was holy – all war that they waged, at least – and holiness was warlike, to a degree that is hard to fathom for us today, even with the presence of movements such as the Islamic State.

“Splendid, too, was torture, which the Assyrian kings looked on as strategic propaganda and sacrificial ritual. Impaling, dismembering, disembowelling, flaying, beheading. The surviving historic friezes celebrated them all, especially beheading.”

As Verini records, in the books of the Old Testament the city is a byword for peerless cruelty: “What the prophets feel in the face of Assyrian abuse is not so much anger as shame, or the white-hot anger that can only come of shame — the shame of men abandoned by their maker.”

Twenty seven centuries before, the Assyrian king Sennacherib had been known for his building projects and beautification programs for Nineveh, including quite possibly the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

In waking dreams Alex walked gracious terraces, looked across oases of date palms, was bowed to by supplicants as the desert air began to heat into the day.

In 21st Century reality the place was a torture chamber; and nobody could have imagined that “the great city” could end like this, in ruins.

Below are links to John Stapleton’s series of books on contemporary Australian history. All of them use the same technique of recording events through the eyes of a retired newspaper reporter, shifting from internal monologues to street scenes to news reports and analysis.