David Carter, The University of Queensland

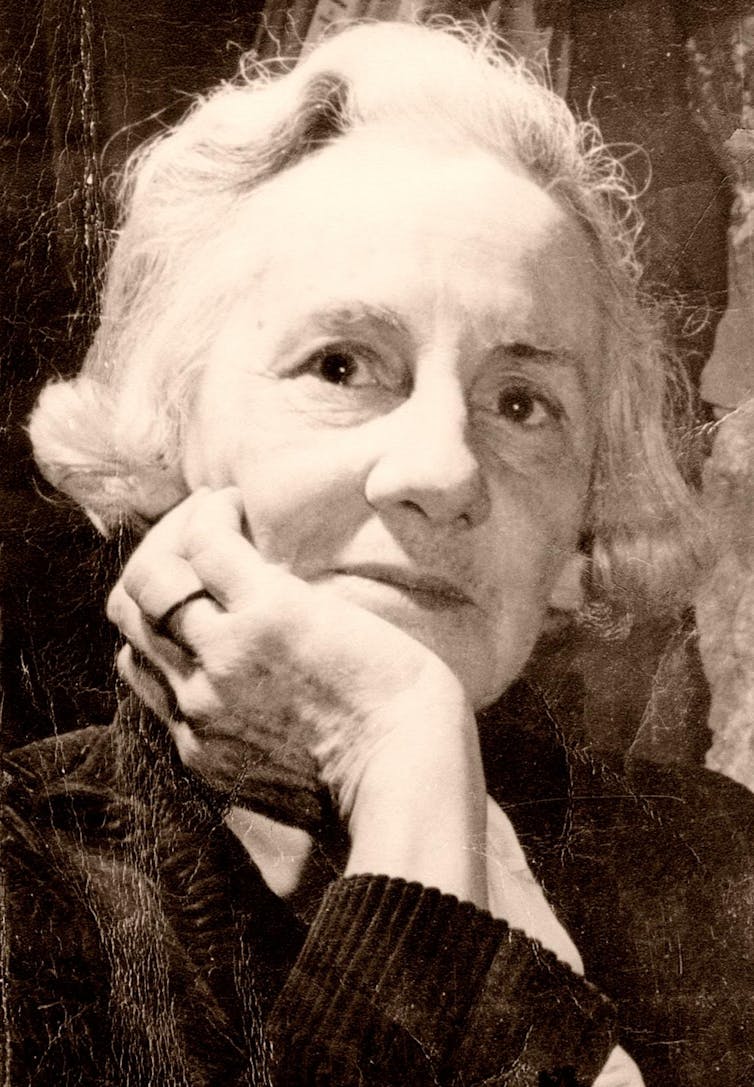

Nathan Hobby’s The Red Witch: A Biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard takes on the challenging task of sorting out the complicated details of Prichard’s life as a child, sibling, governess, teacher, friend, lover, wife, mother, aunt, grandmother, traveller, celebrity, journalist, poet, novelist, short-story writer, social activist, public speaker and communist.

Prichard spent critical years as a wife and widow writing fiction in her Western Australian home, but the image of her as an isolated writer captures only a small fraction of an otherwise crowded and committed public life.

Review: The Red Witch: A Biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard – Nathan Hobby (Miegunyah Press).

It is remarkable that we have had no full-scale independent biography of Prichard to this date. There has been nothing since the work of her son Ric Throssell, who edited two volumes of his mother’s writing and published a biography, Wild Weeds and Windflowers: The Life and Letters of Katharine Susannah Prichard (1975).

So The Red Witch is timely. It will prompt what we might call “recalibrations” of Prichard’s life – adjustments to how we imagine the life and the combined literary and political careers – even if it is unlikely to produce any major reassessment of her standing as a writer or, for that matter, a political activist.

It can be read alongside works by figures such as Carole Ferrier and Drusilla Modjeska, and later literary scholars, who have been rediscovering the role of Australian women as novelists, journalists and critics in the interwar and postwar decades.

Passionate, seductive, direct

Prichard is a key figure in Australian literary history, a key figure in Australia’s intellectual history, and a key figure in Australia’s left-wing political history.

These are challenging dimensions to summon and sustain in a single narrative, not least a biography that is centrally concerned with the details of its subject’s family and friendships, her aspirations and fears, her domestic presence, her colleagues and comrades, and her sexual life.

Hobby manages the shifting focus of these concerns clearly, in such a way that there is no simple separation of public and private spheres. Friends and collaborators were continually struck by Prichard’s thoughtfulness and sensitivity in the public domain. But there are also few moments of private or intimate life that are free from the tensions and obligations of public, political or intellectual involvement.

Prichard was controversial as a communist activist, for those inclined to discover such controversy, but her friendships and family ties were seldom bound to political allegiance in any narrow way. They were more often defined by the intensity and commitment of the friendship she asked for and offered. Her letters share the passionate language of her fiction and some of its seductiveness, but also its toughness and directness.

Political commitments

The Red Witch is not written for “scholars”, Hobby explains, despite Prichard’s ongoing interest for literary critics and historians. It has been written for

a general readership drawn to the peculiar pleasures of biography: the true drama of a life, the glimpses of a lost but familiar world, the recoverable details of the past.

Hobby aims to show a “lived life”. The biography is largely successful in this aim.

Prichard’s father, a committed journalist and editor, was an arch-conservative. He was religious, later depressed, and eventually suicidal. The early portraits of him in Fiji with his family at the time of Prichard’s birth remain entangled in much of the story beyond his life, despite the “outrageous” distance Prichard travelled from her father’s aspirations.

Prichard’s early religious entanglements were in dialogue with her father. So were her later departures towards the causes of labour, women’s rights and socialism.

Her initiative and originality emerged early in her taking on the tasks of governess, teacher, part-time student, and then journalist. These qualities were evident, too, in her early writing and involvement in local drama societies. Early contacts became lifelong friendships. She remained on close terms with Hilda Bull (later Hilda Esson), Nettie Palmer, and Christian Jollie Smith – three women who also had remarkable careers.

In May 1906, with Prichard aged 22, the first episode of her series “A City Girl in Central Australia” appeared in New Idea. Soon after, she met her “Preux Chevalier”, W.T. Reay, a married newspaper editor and politician, who, the evidence suggests, became her lover, his presence “coinciding” with her stays in London, Paris and Australian cities.

Prichard remained a great traveller. Hobby also underscores the significance of Melbourne in Prichard’s maturation as a writer and in shaping her complicated political engagements. Her family connections and her activities in journalism and literary circles led to influential contacts, from Alfred Deakin to the academic and essayist Walter Murdoch, the poet Bernard O’Dowd and, later, Miles Franklin.

Prichard’s politics developed over the same period, through the whole range of socialist philosophies. She embraced pro-suffragist, rationalist and materialist positions, with what Prichard herself later called “idealistic naivety”.

The Great War confirmed her left-wing politics. She voted no in the second (not the first) referendum on conscription. Her commitment to peace was cemented in place at this stage, not least because of her brother’s death in France.

The Russian Revolution would reinforce the directions her politics were taking, although its effect was largely delayed until the 1920s. Prichard was famously a founding member of the Communist Party of Australia in 1920, but her full political engagement did not materialise until the 1930s and 1940s.

Prichard’s political activity in this period, and right through to the 1960s, is extraordinary. She participated in a wide range of social groups, left-wing and women’s associations, the Movement Against War and Fascism, the Writers’ League, the Australian Peace Council, and many more.

Her support of communism and the Soviet Union remained firm from the 1920s on. In her utopian book The Real Russia (1935), she displays an extraordinary passion and, in her own way, a modernist desire for change.

A novelist of nature, region and character

Prichard’s career as a novelist began in London, where she wrote Windlestraws, a “forgettable light romance” (albeit with an intriguing plot) that was not published until 1916, and her first published book The Pioneers (1915), which won Hodder & Stoughton’s prize for novels from “colonial and Indian authors”.

The Pioneers has recently attracted new critical interest for its romantic investments, but also for its complicated portrayal of the Australian bush, its relative “quietness”, and its structure and characterisation. Prichard’s potential significance for literature, and Australian literature in particular, was noted in reviews at the time.

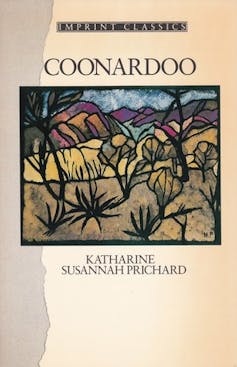

Hobby identifies Prichard’s major creative period as extending from the novel Black Opal (1921) through to Haxby’s Circus (1930), a period that incorporates what remains her most read work, Coonardoo (1929), plus major short stories and drama.

Intimate Strangers, published in 1937 after numerous delays and revisions, just misses out in this listing, but its stories of sexual desire and violence and its psychological entanglements remain confronting.

What comes across throughout much of The Red Witch, right through to Prichard’s death, and alongside her sensuous identifications with nature, region and character, is the “unglamorous” dimension of the life of a working writer (with the adjective understood in its fullest sense).

The biography records this sense of her, evident from early existing notebooks through to her goldfields trilogy – The Roaring Nineties (1946), Golden Miles (1948), and Winged Seeds (1950) – and her last novel Subtle Flame (1967), published just two years before her death. It also reminds us that Prichard’s short stories and plays – and her poetry – are much less known than her novels.

Hobby covers the recent controversies surrounding Aboriginal representation in Coonardoo, but asserts the novel’s ongoing power. The goldfields trilogy has also attracted recent criticism. The trilogy’s take on historical scale and its persistent concern with key Aboriginal characters has been re-evaulated. Miles Franklin, it’s interesting to see, was one of the first to emphasise the central role of both women and Aboriginal peoples in Prichard’s fiction.

Prichard’s life was marked by the suicide of those closest to her — her father and then her husband, Hugo Throssell — and beyond her marriage by threats of sexual violence or rape. Personal life often exposed the tensions between fidelity, desire and intimate relations.

These later elements reappear directly or indirectly in her fiction, making it edgier and more powerful than the work of many of her contemporaries. It is more powerful, too, than any simple celebration of rural or regional Australia, for the two dimensions can be closely linked. There is little in Prichard’s fiction that sits comfortably with more mainstream investments in the Australian bush.

Lovers and marriage

Prichard’s marriage to Hugo is, of course, central to the story, although it is placed here in the context of other romances, before and after. If a slow starter, Prichard was not addicted to celibacy, though close relationships seem more important to her than sex itself.

Hobby emphasises tensions and differences within Prichard’s marriage. Difficult marriages are analysed, sharply, if sometimes comically, in Prichard’s writing. But she kept returning to the marriage throughout the rest of her career, investing in the bonds of love and intimacy it represented. Her absence overseas when Hugo committed suicide no doubt burnt the story deeply into her sense of self and community.

Nathan Hobby offers a full account of Prichard’s private and public lives, but – if I can read now as a literary scholar rather than a general reader – The Red Witch presents only limited interpretations of Prichard’s fiction. It considers how and why her writing mattered in the past and again today, and the way the distinctive qualities of her literary work are often reproduced in her letters and other writings, but such readings are often present only in a sentence or two.

Similarly, The Red Witch offers only “notes towards” a sense of Prichard’s engagement in the intellectual history that her politics and literary aspirations demanded. Her extensive reading of Marx and other political literature is noted, but little of the intellectual or political imperatives of such reading at such a time is explored.

Despite disagreeing with the Communist Party’s recent criticism of the Soviet Union, Prichard paid up her membership three days before her death in October 1969. Events such as the Spanish Civil War and Soviet communism itself are sometimes presented as being very remote from readers’ understanding. (The book’s referencing system asks a good deal from readers too!)

The Red Witch joins a cluster of recent publications about Australian women authors from the interwar and post-war decades. This year has given us Georgina Arnott’s edited Judith Wright: Selected Writings and Ann-Marie Priest’s My Tongue Is My Own: A Life of Gwen Harwood. Last year saw Eleanor Hogan’s Into the Loneliness, her account of the “unholy alliance” between Ernestine Hill and Daisy Bates.

Previous years saw new work on Miles Franklin, Nettie Palmer, Henry Handel Richardson, Zora Cross, Dymphna Cusack and Aileen Palmer. There was also Arnott’s biographical take on Judith Wright, The Unknown Judith Wright (2016), and further back Susan Sheridan’s Nine Lives: Postwar Women Writers Making Their Mark (2011).

This cluster of titles suggests that we now have a rich archive of stories and studies of these writers’ lives and their personal and intellectual networks.

And yet my impression at the moment is that the institutional structures and support for such a grouping are disappearing rather than emerging, despite the enthusiasm we see for contemporary Australian fiction in our festivals, bookstores, reading groups, and among new postgraduates. Let’s hope The Red Witch attracts new readers, for much of it will be news to many.

David Carter, Professor emeritus, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

June 18, 2022 at 12:36 pm

Thanks for the mention, and thanks for a superb review.

I owe my discovery of KSP to Nathan, and was thrilled to host the online launch of the Red Witch. We need more of these literary bios written for the general reader, and not just bios of women, because some of our male writers have been neglected too, if not by scholars, but by a general readership.

June 19, 2022 at 2:37 am

You are so correct. We have essentially forgotten or abandoned our own literary history. Do you know anyone of the current generation, for example, who has read a single word Patrick White wrote; despite being a Nobel Prize winner. Or what about Roland Robinson, who I met several times and was a truly remarkable character. https://pennyspoetry.fandom.com/wiki/Roland_Robinson_(poet) A Sense of Place Magazine is very open to more of these stories celebrating Australia’s literary history; I will send you my contact details. Regards. John Stapleton. Editor.

June 19, 2022 at 4:35 pm

Ah well, I don’t do poetry on my blog, so I’m guilty on that score too.

But Patrick White has an honoured place there , along with some other neglected authors…

https://anzlitlovers.com/author-pages/

cheers

Lisa