By Stephen Saunders: Independent Australia.

‘His opponents will only assist the marketing-man-turned-prime-minister if they continue to underestimate him.’

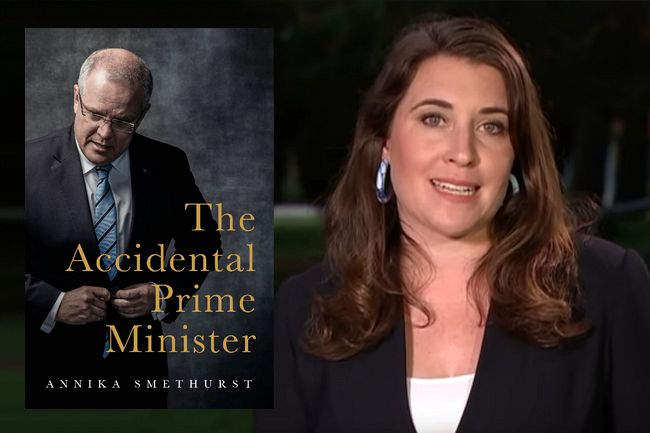

So goes the final sentence and key takeaway of The Accidental Prime Minister.

Annika Smethurst, now state political editor at The Age, made her early reputation at the Herald Sun. Two Walkley Awards carry her name. When she was with Sunday Telegraph, the AFP raided her home, turning newshound into news.

As she recuperated, publisher Louise Adler suggested this book, which unwraps just weeks ahead of Sean Kelly’s Morrison study.

Morrison agreed to be interviewed, as did 70 other colleagues or associates. Fearing ‘blowback’, many prefer not to be named, including women who dislike him.

What shines throughout is Morrison’s capacity to bend the system in favour of his ‘incredible self-belief’. That doesn’t mean his ascent is a ‘God thing’, as put forth by the wife of Bruce Baird, the mentor who drew him into the Liberal Party.

AFP raids: An assault on journalistic freedom

If you wanted to praise or blame mortals for Morrison, you could start with the two Johns — his father and former Prime Minister John Howard.

Distinction may be found in Morrison’s family. His great-great-aunt was poet Dame Mary Gilmore. His parents revelled in the theatre. His police inspector Dad, one of his ‘greatest influences’, also rose to Mayor of Waverley municipality. Yet this wasn’t the born-to-rule background of MP Christian Porter, the Minister just cut loose by Morrison.

‘Morrison’s youth,’ the author concludes, ‘was largely shaped by his parents, the church and his local community… His boyhood wasn’t one of struggle, nor was it grand.’

She classifies Howard and Morrison as the only Liberal Prime Ministers ‘entirely’ state-schooled. Now they’re hard-line defenders of national policy and funding that increasingly favours the church schools.

The family might have been ‘forced’ out to western Sydney, had not an aunt offered space in her suburban Bronte house. A fortunate turn, because Morrison got into selective Sydney Boys High then the University of NSW.

He devoted his Applied Economic Geography honours thesis to the Christian Brethren. Could equally have been the rugby union or netball community, he bluffs with Smethurst.

With Dad pushing theology ‘off the table’ career wise and Scott already wed to Jenny, what better time for his “have a go, get a go” philosophy. He and a pal thumbed the venerable Yellow Pages.

Hence, Morrison’s first gig with retail developer Kern Corporation. He soon jumped ship to the Property Council.

There’s wry amusement in Morrison’s rambunctious early career. He trod on toes and still does — at an international level.

He made ‘early exits’ from Australia’s Tourism Task Force, NZ Office of Tourism and Sport, then Tourism Australia. No matter, he’d also run the NSW division of the Liberal Party. Howard recalls his ‘sound political judgment’. He honed his ‘unrelenting hunger’ for polls and research.

The 2007 preselectors for the Cook electorate belted Morrison in first-round voting. No matter, Howard was backing him. It wasn’t the Morrison dirt file, but that of his main opponent Michael Towke which preoccupied the Daily Telegraph.

Towke didn’t even contest Morrison’s second-round triumph, though he later won a damages settlement. It wouldn’t bother Morrison’s backers — their bloke’s gone all the way.

A frustrated John Menadue continues to publish that it wasn’t really Morrison who stopped the boats. However, ‘I Stopped These’ has become a trophy, a meme. And now, Smethurst’s chapter title, covering Morrison’s 2007-13 years, mainly in opposition.

Becoming Minister for Immigration is no escalator to the top. Touting his Operation Sovereign Borders, Morrison changed that. Though he’s described as ‘terribly unhappy’ when Prime Minister Tony Abbott shifted him ‘sideways’ to Social Services.

Morrison’s new ministry pitched him onto the Expenditure Review Committee (ERC) — the storied ministerial cabal that makes or breaks Budget proposals.

Once inside, Morrison appeared to leak from the ERC. He targeted Treasurer Joe Hockey more than Abbott directly. When Malcolm Turnbull and Morrison replaced those two, Morrison kept up the media coziness. He was dubbed the “Tabloid Treasurer”.

Warring against sources: The security state and public interest journalism

His ‘self-claimed unique insight into the public mood’ went awry when it came to the Banking Royal Commission. Yet when Defence Minister Peter Dutton challenged Turnbull in 2018, Morrison became Prime Minister instead. Smethurst notes the predator’s final prayer before he enters the party room for the run-offs.

Smethurst appreciates the importance of a new prime minister’s first ministry and first staff roster. These served Morrison’s purposes in his surprise 2019 Election victory over Bill Shorten. The author has it that Shorten, like Turnbull, underestimated Morrison.

Morrison’s victory speech was a cheery narrative of “quiet Australians” with modest horizons of job, family and home. In Smethurst terms, he puts ‘middle-class, tabloid-reading mums and dads’ and ‘newspaper editors’ ahead of Party factions.

Soon afterwards, it pleased Morrison’s God to pelt him with environmental disasters. Stunning 2019-20 bushfires segued straight into a global pandemic.

Frowning at Morrison’s mid-fires Hawaii holiday, Smethurst perceives a more interesting leader, as regards COVID-19. She cites his National Cabinet creation, his less dogmatic approach to advice proffered by the (then) Chief Medical Officer and other officials.

By April this year, instead of putting the Liberal Party logo on the vaccine deal, Morrison was ducking rollout responsibilities. The COVID-19 chapter ends in July, with his ‘rare decision’ to apologise. Soon enough, he’d reverted to pummelling his rollout critics as heroes of hindsight.

But this intriguing portrait is mostly a political story-so-far. The COVID-19 crisis continues to unfold unpredictably — now add in AUKUS submarine questions. Smethurst, after fully immersing in Morrison’s bold ambitions and calculations, cautiously summarises the ‘potential’ for his prime ministership to ‘unravel’.

If Morrison were to win re-election, there are rumours he ‘might even retire’ mid-term, with Treasurer Josh Frydenberg ‘viewed’ as the next Liberal prime minister. Contrariwise, Smethurst’s fellow journalist Stephen Brook has just refloated the Dutton alternative.

In Morrison’s personal life, the author looks kindly at the family’s long journey to have children. But she has to be concerned that a Generation X leader ‘doesn’t seem to work constructively’ with women. Another personal theme is his religiosity. His calculated plays for faith colleagues and faith voters are difficult to counter.

Parliamentary prayer buddies were an ‘influential’ bloc in his elevation to the leadership. His reluctance to call out religious bigotry shape-shifted into the headline ‘Shorten ignites unholy war’. Electorates turning against Labor in 2019 ‘overwhelmingly had more people of faith than the national average’.

There’s another takeaway from Smethurst — Howard’s Australia is still pervasive.

The Accidental Prime Minister is available from Hachette Australia in hardcover (RRP $39.99) or e-book (RRP $19.99).https://www.youtube.com/embed/1ASd71TeUTs?rel=0&wmode=opaque

Stephen Saunders is a former public servant, consultant and Canberra Times reviewer.