Bernard Collaery exposes the Timor Sea betrayal

Witness K is in court this week, in closed-court proceedings nobody is meant to know about. He is on trial for doing the right thing. With the release of his book, Oil Under Troubled Water, to coincide with Witness K’s plea hearing, ACT lawyer, Bernard Collaery, has raised the stakes on who the real wrong-doers are in this unedifying exposé of the Howard Government’s breach of international law when it spied on it’s cash-strapped neighbour to profit from Timor Sea oil. Callum Foote reports on the momentous political scandal.

Bernard Collaery (image courtesy ABC)

In early April, we met with Bernard Collaery — Australian lawyer, former politician, longtime legal counsel and representative to the Timorese politician and resistance figure Xanana Gusmão. And, according to some in the Federal government, a traitor, maybe terrorist and opposer of Australia’s “national interest”.

Collaery’s new book, Oil Under Troubled Water, recounts of the “unmitigated disaster” which is Timor-Australian relations.

Collaery is the subject of legal action taken by the Australian Government under the auspices of an anti-terrorism act. The prosecution is an effort to gag Collaery and his client, a former ASIO agent known only as Witness K, who allege that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) bugged Timor-Leste during 2003-4 petroleum and maritime border negotiations.

“Rest assured,” Collaery says in an interview with Michael West Media, “I could tell a lot more if I wasn’t silenced under that terrorist law. I could give names, places and dates.” Approximately 33,000 words have been excised from the present volume of his work due to a gag order.

So, what happened in the Timor Sea? And more importantly, why?

Independence Day

On May 2, 2002, the morning of the day of Timor-Leste independence, the newly instituted President Alkatiri signed the Timor Sea Treaty with Australia. Unbeknown to Alkatiri, through his signature, the Timorese and Australian people had just been cheated out of half the riches in the Timor Sea.

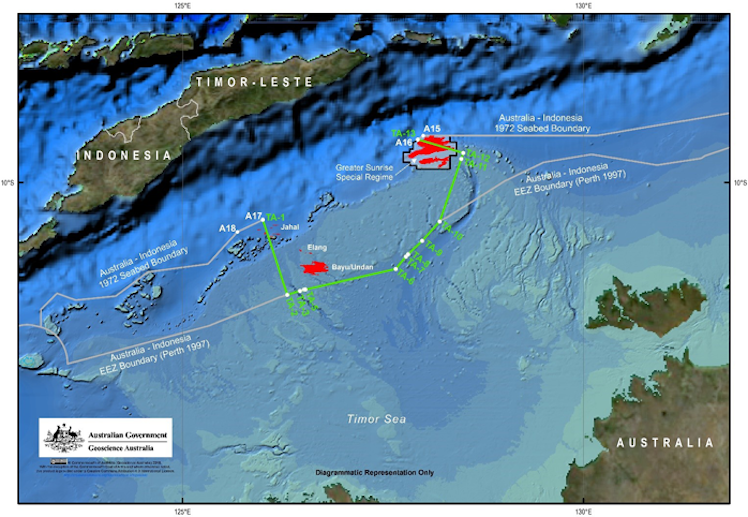

The map shows the location of the maritime boundary which is established by the Treaty Between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Establishing Their Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea. The Treaty was signed by Australia and Timor-Leste on 6 March 2018 in New York.

Former PM John Howard

The treaty was only the latest in a long line of Australian betrayals, and the culmination of an audacious plot hatched between the corridors of government agencies and executive boardrooms supported by Prime Minister John Howard and Foreign Minister Alexander Downer.

President Alkatiri though had much to be grateful for. He and his unreformed Marxist/Leninist FRETILIN party composed primarily from a group of Timorese diasporas who had fled Indonesian occupation for Madagascar, were only instituted as leaders of an independent Timor-Leste as a result of Australian meddling.

Howard and Downer saw FRETILIN as offering the easiest path to an unlawful share of the petroleum reserves in the Timor Sea and so pressured the UN to avoid recognising noted resistance leader Xanana Gusmão’s organized and popular FATILIN as a legitimate political party. Australia also pressured the UN into rushing the near failed state into early independence in order to shorten the time until drilling started.

Naïve in petroleum extraction and lacking any means of obtaining independent advice, the newly formed state was forced to rely on Australia and the word of the consortium if it were to secure the quick revenue base it needed. At the time of independence, Timor-Leste had the lowest GDP per capita in Asia and one of the highest infant mortality rates.

By “edging the Timorese out of billions of dollars and at the same time urging Timor-Leste’s leaders to stabilise their economy by reaching early agreement on [a new oil field] deal, as the gas from the Bayu-Undan field would soon be depleted, was and remains shameless hypocrisy” Collaery writes.

The strategy worked. Howard, Downer and a consortium of largely foreign-owned petroleum companies made off with billions of a critically important national resource.

The helium

The real prize was the vast helium reserves which lay underneath the Timor Sea, with a value almost as great as the petroleum itself. Knowing that it would be impossible to claim the petroleum wholesale, the band of ministers, bureaucrats and executives who represented corporate interests realised they could leverage their expertise and experience over the Timorese and snag the helium from right underneath them.

In a move of almost respectable audacity, DFAT secretly amended the internationally accepted definition of petroleum for the first time to exclude inert gases, including helium which is commonly found within petroleum fields, instead classifying them as “waste material”. What was to be done with this “waste material”? It was given wholesale to the contractor parties — private foreign-owned corporations.

Former East Timor PM, Mari Alkatiri

This move was pulled off because Timor-Leste’s leaders, purposefully starved of resources and time by Australia, could not hire

their own petroleum or maritime experts to vet the contracts and treaties being drawn up in their name. Perhaps the Timorese leaders, convinced of the reputation of both their powerful neighbour and industry leaders Woodside and ConocoPhillips, assumed negotiations were being done in good faith.

Maybe President Alkatiri let down his guard after a face-to-face meetings with Howard, sealed with a handshake and a warm smile.

In depriving a poor state of such a measure of its non-renewable sovereign riches as to affect the capacity of that state to tackle poverty would be an abuse of human rights. And you’d think that Australians would, at least, benefit in some way. Not so.

This deal not only stole Timorese helium reserves, but it also continues to affect Australians. “Extraordinary as it seems,” Collaery writes.

“Australia’s ever-expanding helium needs, particularly in the defence, research and medical spheres, are now met by repurchasing the alleged waste give-away.”

The Timorese story

The Timorese story shows a wider malaise in Australian democracy whereby private interests have, in this case, total control over Australian foreign policy.

Through it, we are left with a legacy of predation and betrayal with both the Timorese and Australian populations missing out on billions of dollars in revenue as “a clique of intelligence-fed ministers and bureaucrats, used Australia’s power and reputation to enhance ill-gotten profits for largely foreign shareholders” writes Collaery.

Even the petroleum extracted from the Timor Sea was never connected to the Australian grid. Instead, like the helium, it is shipped overseas and bought back by Australians at a mark-up.

In our interview, Collaery notes that the corporatisation of Australian foreign policy is following in the footsteps of the US.

“It follows the American model. Board rooms have outflanked the role of diplomacy. It’s now the boardroom to Prime minister, boardroom to the treasurer. The way [our foreign policy] is now has no relation to a working democracy. Its privileged decision making. It’s imperialism.”

Most ministers, with few notable exceptions, have become:

“little but the mouthpiece of a close-knit bureaucracy as successful as ever at finding a surrogate voice to project their narrow machinations.”

In securing the “Holy Grail in the Timor Sea”, the already close working relationship with Australian petroleum exploration and producer Woodside and American multinational ConocoPhillips tightened. For instance, during petroleum-sharing negotiations in 2004, DFAT personnel were “seconded” to Woodside’s offices in the Timorese capital with a draft treaty given over to Woodside in order to proof.

The revolving door

Dr Ashton Calvert

There is a very short and well-worn path between the halls of Canberra and the Woodside boardroom. Collaery notes that in 2005, DFAT Secretary, Dr Ashton Calvert, was appointed to the Woodside board seven months after retiring from his post. It was during Calvert’s time as DFAT Secretary that Australia, with Woodside’s guidance, negotiated with Timor-Leste.

Gary Gray, former National Secretary of the Australian Labor Party, was similarly embedded in Woodside, having been employed as an adviser and eventual Woodside executive board member within a year of resigning.

Former foreign minister Alexander Downer

Downer also took a role as a petroleum lobbyist seven months after retiring from parliament in 2008. In May 2011, Downer went to Dili to discuss with then-President Xanana Gusmao Timor-Leste’s demands for a gas pipeline. It became apparent that Downer’s visit included a consulting role on behalf of Woodside Petroleum. In an effort to secure petroleum and helium reserves in Australia, Woodside had used faked deep-sea modelling as proof that a pipeline to Timor-Leste was unfeasible.

The gag

In 2013, Collaery and an ageing ex-senior ASIS officer known only as Witness K revealed that Australia, despite holding all the cards, had also bugged the Timorese negotiators’ offices.

Armed with this information, Timor-Leste told international arbitration that both the 2004 Timor Sea Treaty and a subsequent 2006 treaty should be nullified. These treaties concern maritime boundaries.

Collaery notes that the only way senior Australian officials “had any hope of staving off the inevitable finding for the first time in modern history of treaty-making fraud” would be to “to use any ploy to prevent the Permanent Court of Arbitration [located in The Hague] reaching a finding”.

What followed can only be described as a series on intimidation tactics which forced Collaery and his team off the case against Australia “including breaching the legal professional privilege of Timor-Leste’s lawyers” by raiding Collaery’s office and home in 2013 and “misleading statements relating to national security, the cancellation of Witness K’s passport and ongoing refusal to grant a replacement passport”.

Democracy in chains

Collaery questions the fundamental basis of Australian government; a government so inept, he says, that its own citizens don’t even benefit from the exploitation of neighbour states.

The Timorese story shows that Australian power and reputation has been abused by a clique of tight-knit bureaucrats, politicians and corporate executives for their own gain.

“The average Australian battling, bringing up their families wants to believe we exist in the basic values of democracy”, says Collaery. “But they don’t, Australians don’t even have a working democracy, treaty licenses which license theft were tabled in the Australian parliament.”

Instead, Collaery sees Canberra as:

“a vast seething Chicago of self-interests, and the only way they’re keeping a lid on it is by issuing prosecution orders against individuals.”

The stories are not over yet though. The riches of the Timor Sea have not yet been exploited. Collaery is still fighting charges in the ACT Supreme Court. The inevitable fallout, if the truth is permitted beyond the curtain of national interest, is monumental.

Collaery leaves us with a question which reflects the cold reality of new Australia:

“Since when did it become a crime to report a crime?”

———————-

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Callum Foote

Callum Foote is Michael West Media’s Revolving Doors editor exposing the links between the highest level of business and government. These links provide well-resourced private interests with significant influence over Australia’s policymaking process. Callum has studied the impact of corporate influence over policy decisions and the impact this has for popular interests. He believes that the more awareness this phenomenon receives the more accountable our representatives will be.

This story was originally published by Michael West Media and is reproduced here with their kind permission.