By Rebekah Barnett: Brownstone Institute

Victorians could go to prison for up to five years for hate speech under new anti-vilification laws proposed by the Victorian Government.

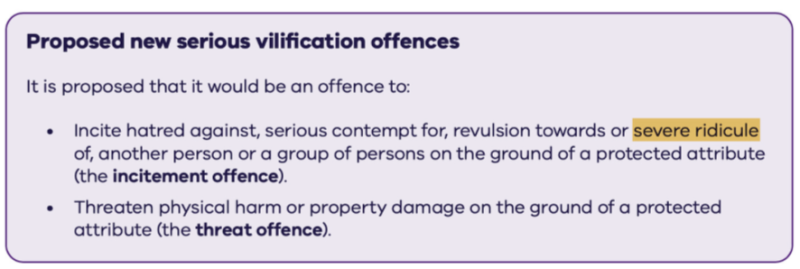

Under the proposed laws, it would be an offence to “incite hatred against, serious contempt for, revulsion towards or severe ridicule” of a person or group based on their sex, gender identity, or race.

It would also be illegal to “threaten physical harm or property damage on the ground of a protected attribute.”

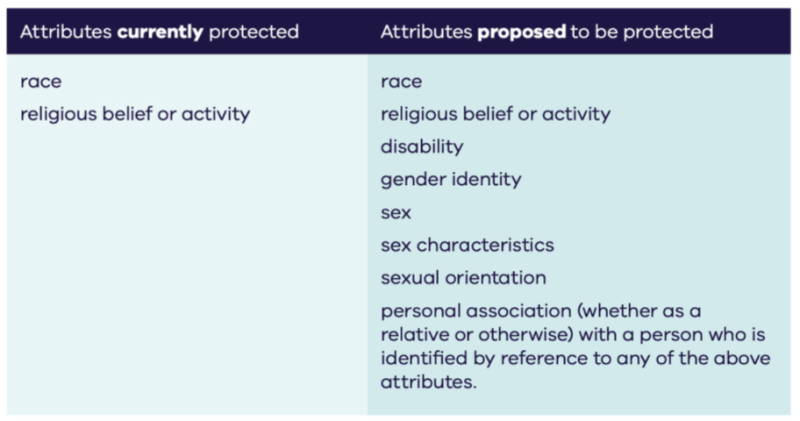

The new laws would lower the legal threshold for prosecuting people for vilification and would add gender identity, sex, sex characteristics, sexual orientation, and disability to the list of protected attributes alongside race and religion, which are already protected.

Online, these laws will apply to anyone, anywhere who vilifies a person in Victoria, although the government acknowledges that this may be difficult to enforce.

Offline, these laws will apply to both public and private interactions.

The changes, which amount to a heavy rewrite of the Racial and Religious Tolerance Act, are intended to “reduce the harm caused by vilification, protect more people, reflect the seriousness of hateful conduct, and ensure those who experience vilification can easily seek help.”

Hate Speech Laws Welcomed by Human Rights, Law, and Special Interest Groups

The Sun Herald reports that the original motivation for the legislation was “due to fears of Islamophobia after women were getting spat on for what they were wearing, but it has “since expanded to address rising anti-Semitism, as well as other attributes including to protect people with disabilities and members of the LGBTIQ+ community.”

The proposed hate speech laws have been welcomed by human rights groups including the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission.

“We need to shift the burden of responding to hate from individual victims and instead create a system that can drive change,” said the Commission, which has played an active role in advocating for stronger legal protections to protect Victorians from hate conduct.

A parliamentary inquiry into anti-vilification protections in 2020 drew strong expressions of support for expanding the anti-vilification legal framework from diverse groups including the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council, the Islamic Council of Victoria, the Law Institute of Victoria, the Online Hate Prevention Institute, Victoria Legal Aid, Equality Australia and the Victorian Pride Lobby.

In its response to the inquiry report, the government committed to strengthening the state’s anti-vilification laws, acknowledging the “profound” impacts of hate conduct and vilification on the physical and psychological wellbeing of individuals and communities, and on “the very core of Victoria’s social cohesion through its inherent divisiveness and unequal distribution of power.”

Since the inquiry wrapped up in 2021, the Victorian Government has undertaken several rounds of consultation, with final consideration of feedback to take place later this year.

Prison Time for Ridicule

However, the proposed anti-vilification laws have not been welcomed in all corners.

“Victoria has a new fight on its hands,” said Victorian MP David Limbrick in a video posted to X. The Libertarian and free speech advocate shared his concerns and called on followers to voice their dissent.

“This is really serious stuff. You can go to jail for three years for ridicule!” he said.

“The government’s definition of public conduct is so broad that it includes private property – does that include your backyard barbeque?

“And how weird is this – they want to include behaviour that incites hatred or other serious emotions. But the government’s actions incite serious emotions in me all the time!”

Indeed, under the proposed reforms, you could be criminally prosecuted for incitement of “severe ridicule” on the grounds of a protected attribute, with a maximum penalty of three years prison time.

Threatening physical harm or property damage would carry a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment.

Currently, the threshold for prosecution is higher and the maximum penalty is lower – both incitement and threat must be proven to prosecute for vilification, and the maximum penalty is six months imprisonment, a fine of up to $11,855.40, or both.

And, it is certainly possible that Victorians could be prosecuted or sued for things said at a backyard barbeque. The proposed criminal incitement offences apply to both public and private conduct, which means that “regardless of whether hate speech or conduct occurs in public or in private, it can be a crime.”

An additional set of civil protections apply only to public conduct, but as pointed out by Limbrick, “conduct might be considered public even if it occurs on private property or at a place not open to the general public,” such as neighbours calling across the fence, or interactions that occur at a school or workplace.

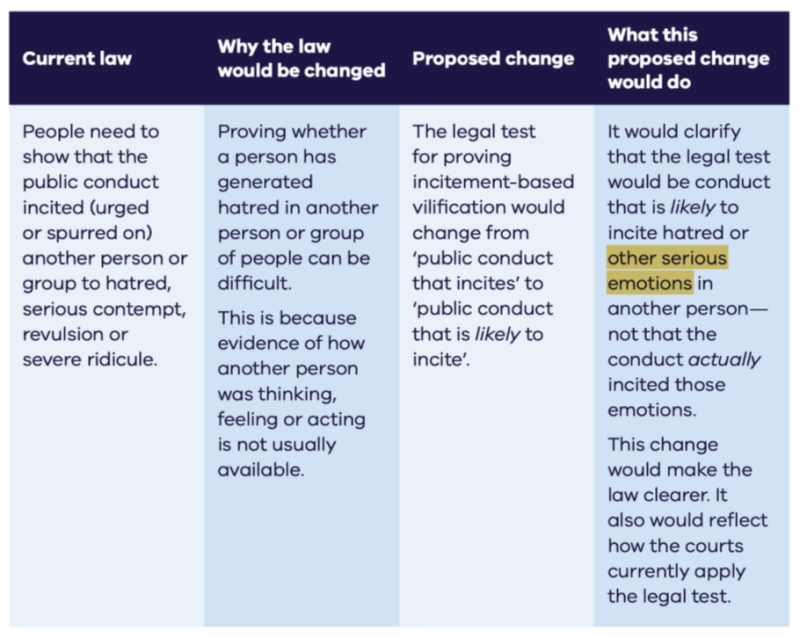

Also under the modified civil protections is the clarification that the legal test for incitement would be “conduct that is likely to incite hatred or other serious emotions in another person.”

Limbrick jokes that the government’s actions incite serious emotions in him all the time, but this provision would be no joking matter for the accused, who could face legal action for inciting serious emotions in relation to someone’s race, gender identity, or disability.

Breastfeeding Advice a Hate Crime?

During parliamentary debate last year, Limbrick attempted to secure assurances from Victoria Attorney-General Jaclyn Symes that the new laws would not prevent Australians from speaking plainly on important issues.

For example, “Can the Attorney-General provide reassurances that the dictionary definition of ‘woman’ – that is, an adult human female – will not be considered hate speech under the proposed anti-vilification laws?” asked Limbrick.

“That is a bit of a stretch,” said Symes.

But is it?

A Victorian breastfeeding counsellor, Jasmine Sussex, is currently being taken to a Queensland tribunal over a vilification claim by trans-identified male Jennifer Buckley, after Sussex raised concerns online about biological males trying to chest-feed newborn babies.

This is the third complaint made by Buckley to various authorities, including the Queensland Human Rights Commission and the e-Safety Commissioner, resulting in Sussex being fired from her volunteer role at the Australian Breastfeeding Association, her social media posts being censored, and now legal action.

The difference under Victoria’s proposed laws is that Sussex could be liable for criminal prosecution and jail time for her proclamations of biological fact, which reportedly hurt Buckley’s feelings.

Principal lawyer at the Human Rights Law Alliance (HRLA) John Steenhof, who is representing Sussex, said in a statement that, “ordinary Australians like Jasmine Sussex should be free to speak openly about issues of public importance.”

“Vilification laws are easily weaponised to silence free speech and suppress opposing views on contentious social issues,” he warned.

This is a concern shared by Dr Rueben Kirkham of the Free Speech Union of Australia (FSU), who describes the proposed laws as “expansive” and “problematic.”

“The origins are Soviet – literally – which tells you a lot about what you need to know,” he said in an email.

Dr Kirkham highlighted a range of concerns including the potential for politicisation of the police force, which would be empowered to initiate prosecutions, the prospect that even “mildly offensive” speech could meet the threshold for legal action, and insufficient provisions for legal defence against accusations.

It is proposed that only conduct or speech engaged in for a “genuine” purpose in the public interest be protected from the scope of the anti-vilification laws, which would require an accused person to prove genuine intent.

“Imagine having to keep records to prove that every tweet is reasonable. We are appalled,“ said Dr Kirkham.

Federal Hate Speech Bill Also in Play

As Victoria works to extend and strengthen its anti-vilification laws, a federal hate speech bill is already moving through the Australian Parliament, targeting speech and conduct that recklessly incites violence against people because of their race, religion, and other protected attributes.

The federal bill is less extreme than the laws proposed by the Victorian Government, and has drawn criticism from some special interest groups for not going far enough.

The Criminal Code Amendment (Hate Crimes) Bill 2024 will strengthen existing offences to reduce the fault element to ‘recklessness,’ will remove the “good faith” defence, will expand the list of prohibited hate symbols, and will create new criminal offences for threatening force or violence against targeted groups.

United Kingdom Hate Crime Laws a Taste of What’s to Come?

In April of this year, Scotland passed laws making it a crime to “stir up hatred” against protected groups, with a maximum prison sentence of seven years.

Similarities between the Scottish laws and those proposed by the Victorian Government can offer a sense of what Victorians might expect: a large uptick in reported hate crimes, a moderate number of successful prosecutions, and an increased burden on the police force.

More than 7,000 hate incident complaints were reportedly made to the Scottish police in the first week after the hate crime laws came into effect. Ironically, many were in relation to an infamous 2020 speech by then First Minister Humza Yousaf in which he bemoaned the ‘whiteness’ of the leadership class in Scotland (a country in which 96% of the population is white), showing that vexatious complaints can go both ways.

While no action has been taken on a majority of anonymous and vexatious complaints, Police Scotland reports that between April and September, 468 hate crimes had progressed to some form of prosecutorial action. Forty-two cases resulted in conviction, while more than 80% of cases are still moving through the courts.

Aside from successful prosecutions, Scotland’s new hate crime laws have coincided with an upsurge in recorded hate crimes. In the six months since the laws came into effect, Police Scotland recorded 5,400 hate crimes, representing an increase of 63%.

Justice Secretary Angela Constance said that the increased number of recorded hate crimes “demonstrates that this legislation is required and needed to protect marginalised and vulnerable communities most at risk of racial hatred and prejudice.”

On the other hand, opposition justice spokesperson Sharon Dowey said that the increase in reports highlighted the strain that the new laws were having on Scotland’s “overstretched” police force, which includes hate crime training as well as attending to reports.

Arrests and prosecutions in Britain in the wake of racially charged protests and riots this year related to the stabbing of three children in Southport, and the related issue of mass immigration, offer insight into how hate speech laws may be applied in times of inflamed social tensions.

In response to the riots, the Starmer Government assigned specialist officers to investigate hundreds of social media posts suspected of “spreading hate and inciting violence.”

Law enforcers arrested hundreds and sent multiple people to jail under a hodgepodge of legal provisions including “stirring up racial hatred,” “sending false communications,” or causing public disorder, either on social media or at the protests.

Some of these cases involved outright calls to violence, while others said offensive things, inadvertently shared false information or were merely onlookers to riots, in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Stark Naked Brief noted “bizarre inconsistencies” in the application of the subjectively worded laws hate speech laws, with some – like “keyboard warrior” Wayne O’Rourke, who was sentenced to three years in prison for “stirring up racial hatred” on social media – receiving longer prison time for hate speech and conduct than actual murderers.

Speech under Siege

The proposed hate speech laws are just several of a grab-bag of reforms that, if passed, will necessarily curtail free speech, both on and offline.

In the past month, the Australian Government has tabled a bill to combat misinformation and disinformation, and committed to legislation imposing social media age limits, which experts anticipate will usher in Digital ID to verify the age of all Australian internet users.

New privacy laws criminalising doxxing have also been tabled, which critics are concerned will have a chilling effect on legitimate speech, and a statutory review of the Online Safety Act looks set to expand the eSafety Commissioner’s powers over online platforms and content.

While these laws may be well-intentioned, an (unintended?) effect will certainly be to put free speech under siege Down Under.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.

Rebekah Barnett is a Brownstone Institute fellow, independent journalist and advocate for Australians injured by the Covid vaccines. She holds a BA in Communications from the University of Western Australia, and writes for her Substack, Dystopian Down Under.