Rebekka Barnett: Dystopian Down Under

Misinformation research is a joke, but not in the haha way.

Today, I submitted my feedback to the Australian Government on the Communications Legislation Amendment (Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation) Bill 2023.

If passed, the bill will considerably expand the regulatory powers of the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) over digital platforms, essentially forcing platforms to comply with codes and standards devised by ACMA to counter misinformation and disinformation (currently, adherence to the Australian code is voluntary).

These powers are necessary, says ACMA, because misinformation and disinformation are becoming more pervasive, and will cause harm.

Except, the research underpinning the bill does not support ACMA’s claims.

Misinformation and harm – by what measure?

In order to justify new legislation, governments have to demonstrate the need for it. ACMA fails on this first and most basic premise.

In a report explaining the research and rationale behind its bill, ACMA states that, “the true scale and volume of misinformation in Australia is currently unknown.” (emphasis mine)

The report references “increasing concern” about a perceived increase in “misinformation” online, measured by survey respondents reporting how much misinformation they believe they have seen. However, this conflates reports of misinformation with actual misinformation.

Conflating subjective user reports with actual instances of misinformation and online harm is common in government and peak body reporting in this field. Other potential factors that may give rise to an increase in reports of misinformation and online hate, such as increased social sensitivity, better promotion of reporting tools, and the impacts of cultural developments (e.g.: political polarisation) are rarely explored.

It bears noting that government officials frequently stress that reports of perceived physical harms on pharmacovigilance databases associated with, say, Covid vaccines, should not be misconstrued as instances of actual harm. Alternative explanations for reports of perceived harm are typically proffered, with the onus of proof being put onto those who wish to demonstrate a causal link between reports of harm, and actual harm.

By the same token, ACMA should demonstrate that perceptions of an increase in misinformation online, and perceptions of resultant harm, correspond with an actual increase in misinformation and harm. They haven’t done this.

ACMA

ACMA uses three case studies in an effort to demonstrate how misinformation and disinformation cause harm, but fails to achieve its aim.

The first case study is the US riot on 6 Jan 2021. But ACMA’s retelling includes misinformation. ACMA attributes the unrelated deaths of several people who died of natural causes to the riot, raising questions about ACMA’s ability to reliably discern true information from misinformation.

Second, ACMA refers to research showing that anti-vaccine content (even if true and accurate) can sway people’s vaccination intentions, but does not demonstrate how this causes harm, and to what extent.

A third case study on the real-world impacts of anti-5G content makes a more convincing demonstration of fiscal harm resulting from information classified by researchers and ACMA as misinformation.

However, it is unclear as to how the proposed measures in this bill will prevent such harm – there appears to be an inherent assumption that online censorship of certain information will reduce real world harm, but current research shows that censorship simply encourages users to find work-arounds, a fact acknowledged by ACMA in the report.

ACMA has failed to sufficiently demonstrate the volume and scale of misinformation and disinformation and its purported harms, or give any insight into how their bill will ameliorate these imagined harms.

What misinformation and disinformation actually entails, according to the bill, reveals another layer of flawed logic, as ACMA’s definitions are circular.

The government is always right, and everything else is misinformation

The principal study of misinformation in Australia used by ACMA to inform its draft legislation (by the News & Media Research Centre, University of Canberra) categorises beliefs that are contradictory with official government advice as ‘misinformation’, regardless of the accuracy or contestability of the advice.

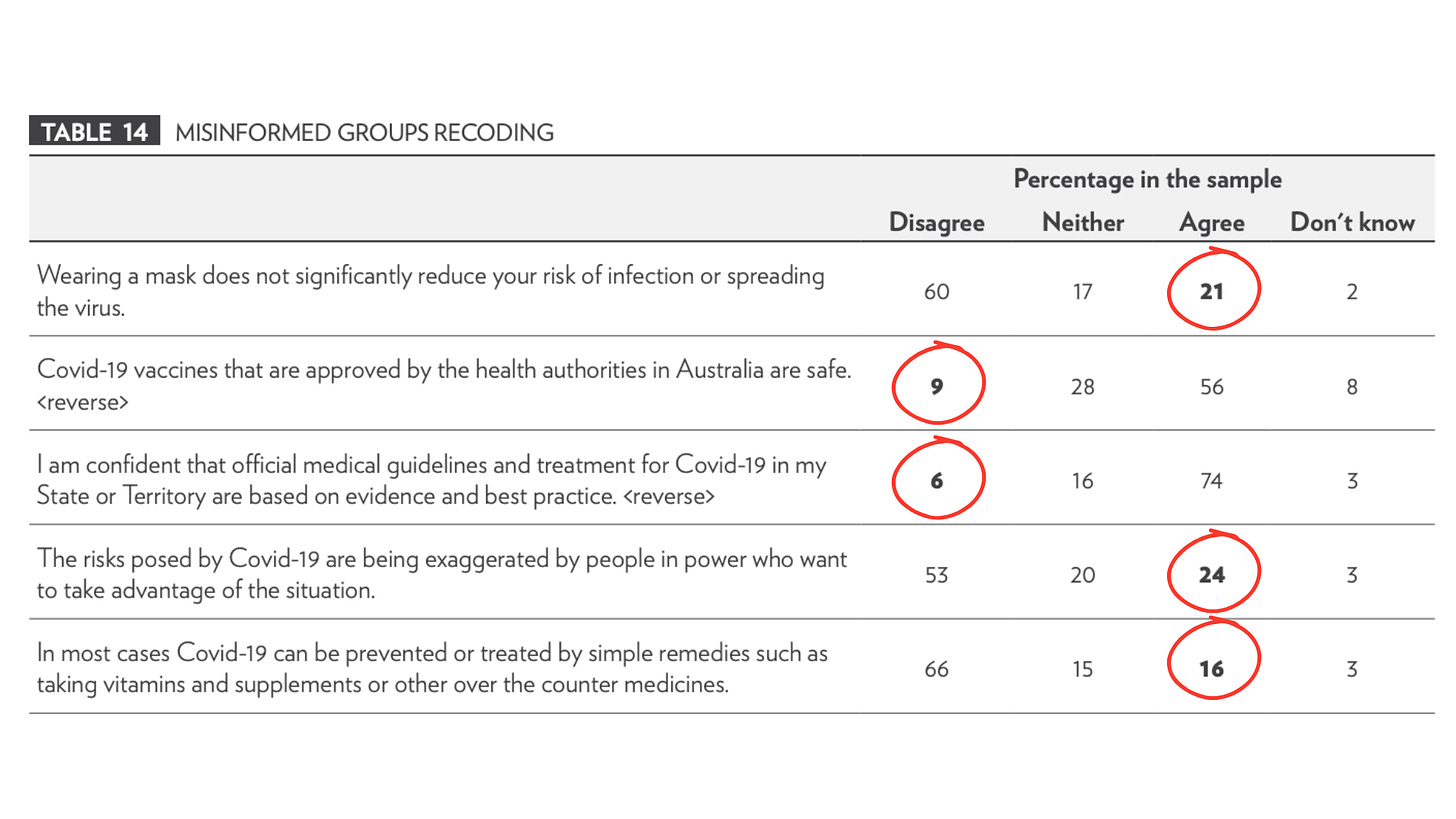

This can be seen in the below table showing that respondents are coded as ‘misinformed’ if they:

a) Agree that wearing a mask does not significantly reduce your risk of infection or spreading the virus;

b) Disagree that the Covid vaccines that are approved by the health authorities are safe; or,

c) Agree that in most cases, Covid can be prevented or treated by taking vitamins and supplements or other over the counter medicines.

All three of these positions are supported by peer-reviewed scientific literature, but are in opposition to official government/health authorities’ advice. It is obviously incorrect to categorise these respondents as misinformed. What the researchers really mean, is that these respondents believe information that contradicts the official position.

The other study commissioned by ACMA, a social media content and network analysis by creative consultancy We Are Social,

2 makes the same error – the researchers mislabel scientifically-supported concerns as ‘conspiracy’ and ‘misinformation.’

Four ‘misinformation narratives’ are examined in the study, including ‘anti-lockdown conversation’ and ‘anti-vax conversation’ (by which I presume that We Are Social has forgone the traditional meaning of ‘anti-vax’ – anti-all vaccines – for the new meaning in common parlance, i.e., ‘skeptical of the safety and/or efficacy of Covid vaccines’, which is itself disinformation).

At least two of the four identified ‘misinformation narratives’ are supported by a body of scientific literature and observational reports, such as cost-benefit analyses, so we see that what We Are Social really meant was ‘narratives that undermine the official position.’

Based on these studies, ACMA states that, “Belief in COVID-19 falsehoods or unproven claims appears to be related to high exposure to online misinformation and a lack of trust in news outlets or authoritative sources.”

This is unsupported by their own research, which instead shows,

“Belief in positions alternative to the official position appears to be related to high exposure to alternative viewpoints and a lack of trust in news outlets or authoritative sources.”

Is this a bad thing? ACMA says yes, but again, their reasoning is circular.

Flawed research leads to flawed policy

The conceptual foundation of ACMA’s bill, informed by flawed research, categorises all opinions running counter to the government line as misinformed.

This faulty logic is baked into the bill by the explicit exclusion of content produced by government, accredited educational institutions, and professional news from the definitions of misinformation and disinformation.

This is a departure from the traditional definitions for misinformation and disinformation, which encompass all information that is false or misleading, either unknowingly (misinformation) or with the intention to deceive (disinformation), and do not exclude information/content based purely on its source.

ACMA offers no rationale for excluding some sources of misinformation from its proposed regulatory powers, but not others.

The exclusion of information from government, approved institutions and the press from the regulatory reach of the bill, coupled with the assumption that misinformation and disinformation (from non-government or non-institutionally-approved sources only) can cause a broad range of harms, implies practical application that looks something like,

‘The policies of governments and peak/governing bodies save lives and are intrinsically good for the nation, or the world. Ergo, any information counter to these policies threatens lives and causes harm.’

When adopted in the marketplace, policies underwritten by such logic read like YouTube’s medical misinformation rules, which categorise as misinformation any information that, “contradicts local health authorities’ (LHA’s) or the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidance about specific health conditions and substances.”

As Michael Shellenberger pointed out earlier this week, if YouTube had existed over the past 200 years, then under such a policy they would have banned criticisms of blood-letting, thalidomide, lobotomies, and sterilising the mentally ill, all of which were recommended by official health authorities at one point in time.

Should ACMA’s bill pass in its current form and become law, digital platforms will be compelled to take a similar line. This is not only flawed, it’s dangerous.

Paving the road to catastrophe

In the past, extreme censorship of dissenting speech has led to mass casualty events, such as the Soviet famine of the 1930s brought on by Lysenkoism. Biologist Trofim Lysenko’s unscientific agrarian policies were treated as gospel by Stalin’s censorious Communist regime.

It is reported that thousands of dissenting scientists were dismissed, imprisoned, or executed for their efforts to challenge Lysenko’s policies. Up to 10 million lives were lost in the resultant famine – lives that could have been saved had the regime allowed the expression of viewpoints counter to the official position. (Credit to Alison Bevege for first drawing the Lysenko comparison on her Substack, Letters From Australia)

History tells us that censorship regimes never end well, though it may take a generation for the deadliest consequences to play out. ACMA’s draft legislation will go to review following a period of public consultation, which closes today. Hopefully, the Australian Government will take the historical lesson and steer Australia off this treacherous path.

My recommendation, made in partnership with Australians for Science and Freedom, is that the bill be abandoned entirely, though I think this is an unlikely outcome given the resources already poured into creating it.

I suspect the government will put it on the back burner and try again later, or they’ll do what the UK government did following public feedback on digital ID expansion, and simply brush off considerable public opposition as evidence of a woefully misinformed populace requiring of government intervention to keep them from drawing incorrect conclusions.

Misinformation research has a long way to go if it’s to be taken seriously

I would also hope that the field of misinformation research will take a reality check, though this too seems unlikely.

Just this week, JAMA published a study on misinformation that is unintentionally full of misinformation. You can read a summary of the factual errors made by the authors of the study, Communication of COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media by Physicians in the US, by Vinay Prasad here, or by Tracy Høeg here.

The logical fallacy of conflating ‘true information’ with ‘the official position’ continues to abound in misinformation research, as does the conflation of ‘distrust of government/authoritative sources’ with ‘misinformed’, ‘conspiracy theorist’, or ‘anti-science’. (See el gato’s post here)

Another logical fallacy, ‘guilt by association’ continues to be routinely employed by researchers and reporters who should know better, but apparently don’t, or do but don’t care. See as example, this Washington Post article, and this commentary from Alison Bevege on the We Are Social study.

I suggest three remedial actions that misinformation researchers can take to regain credibility.

First, misinformation researchers ought to try to find out why certain groups distrust official sources.

For example, Mark Skidmore conducted a survey from which he determined that people who believed they had witnessed vaccine injury in their personal circles were less likely to want to take the vaccine themselves (and probably less likely to trust that it is as “safe and effective” as the government insists). This was a great insight, although pro-vaccine activists forced a retraction of the paper because they didn’t like his other finding, that Covid vaccine fatalities were likely higher than captured in official data.

Second, misinformation researchers should conduct a review of their own field of research, documenting the instances of misinformation and logical fallacies in their own collective body of work.

This should be used to stimulate vigorous academic debate over what constitutes misinformation, why misinformation is so difficult to adjudicate, and how the information environment can be best managed without propping up misinformation from certain sources (government, ‘experts’) and suppressing necessary dissenting information from other sources (scientists, the proletariat).

Finally, misinformation researchers should examine past instances of mass censorship, and produce reports reflecting on the historical lessons that can be gleaned from such regimes.

If misinformation researchers can do these three things, they might be able to turn the joke around. But I don’t think this will happen. Governments and big industry (pharma, energy, etc) are getting too much upside from maintaining the status quo to consider funding this kind of research, and the high-impact journals appear to be corrupted to such a degree that they are no longer concerned about maintaining an aura of credibility, such that they’ll even publish studies on misinformation that are full of misinformation, provided that the conclusions fall in line with government and big industry’s goals.

Rebekah Barnett reports from Western Australia. She holds a BA Comms from the University of Western Australia and volunteers for Jab Injuries Australia. When it comes to a new generation of journalists born out of this difficult time in our history, she is one of the brightest stars in the firmament. You can follow her work and support Australian independent journalism with a paid subscription or one off donation via her Substack page Dystopian Down Under.