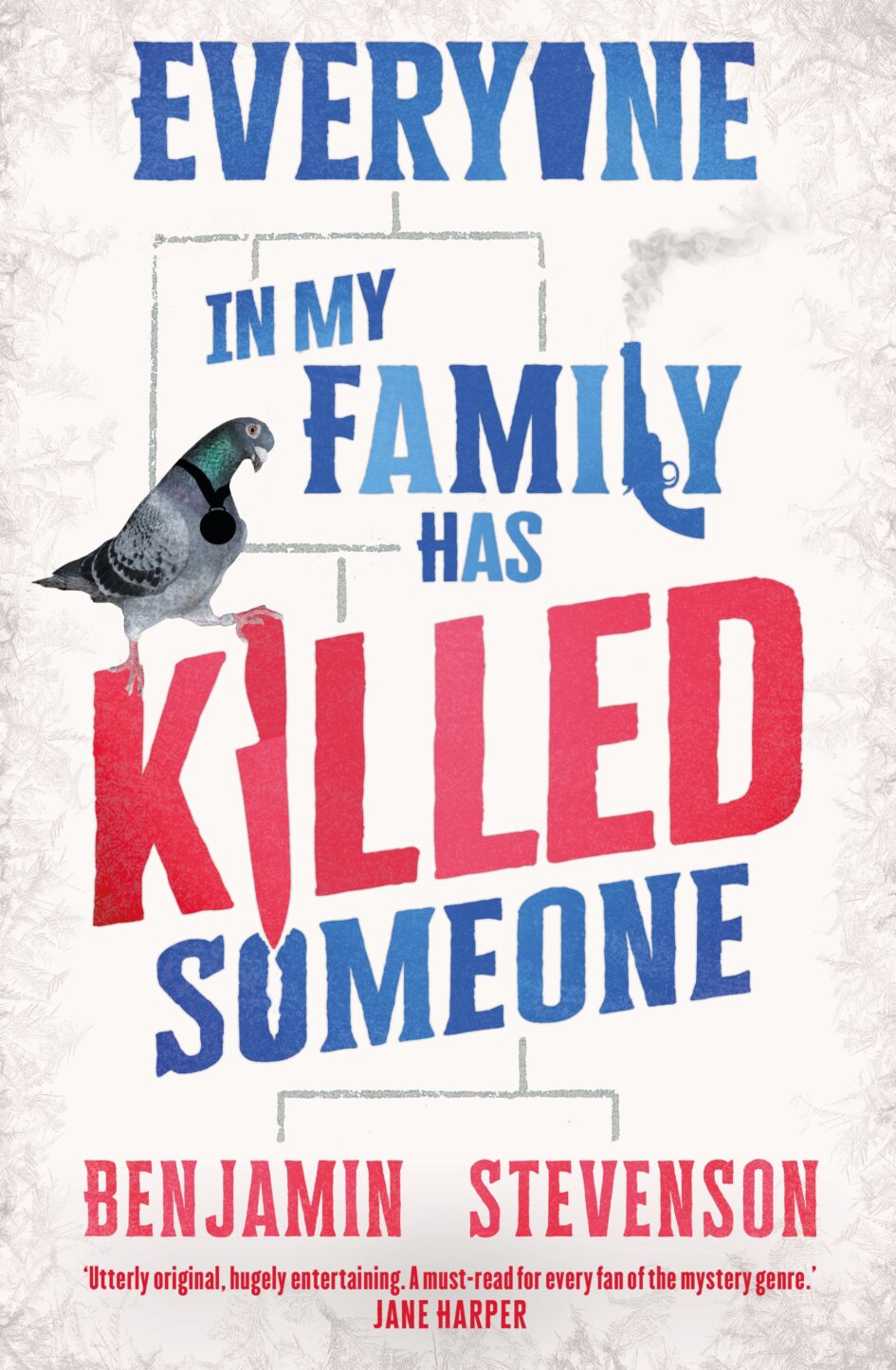

Extract: Benjamin Stevenson.

Badged as: THE AUSTRALIAN NOVEL THAT WILL HAVE EVERYONE TALKING IN 2022!

Praise has been extremely high.

Amazon reports: Following a heated auction in Hollywood, film/TV rights were sold to HBO. Major rights deals have been completed in the US, UK and 16 translation territories so far!

Praise has been over the top:

‘I absolutely loved it. Utterly original, hugely entertaining, and a must-read for every fan of the mystery genre.’ Jane Harper.

If you’re a classic murder mystery fan looking for something fresh and original, you will absolutely love this. I did.’ Anna Downes

‘The best opening to a crime novel I’ve ever read. I loved every page of it.’ Jack Heath.

Benjamin Stevenson is an award-winning stand-up comedian and author. He has sold out shows from the Melbourne International Comedy Festival all the way to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Off-stage, Benjamin has worked for publishing houses and literary agencies in Australia and the USA. He is also the author of Greenlight and Either Side of Midnight.

Here is an extract from his latest blockbuster.

Everyone in my family has killed someone. Some of us, the high achievers, have killed more than once.

I’m not trying to be dramatic, but it is the truth, and when I was faced with writing this down, difficult as it is with one hand, I realised that telling the truth was the only way to do it. It sounds obvious, but modern mystery novels forget that sometimes. They’ve become more about the tricks the author can deploy: what’s up their sleeve instead of what’s in their hand. Honesty is what sets apart what we call ‘Golden Age’ mysteries: the Christies, the Chestertons. I know this because I write books about how to write books. There are rules, is the thing. A bloke named Ronald Knox was part of the gang and wrote down a set once, though he called them his ‘Commandments’. They’re in the first part of this book in the epigraph that everyone always skips but, trust me, it’s worth going back to. Actually, you should dog-ear it. I won’t bore you with the details here but it boils down to this: the Golden Rule of the Golden Age is play fair.

Of course, this isn’t a novel. All of this happened to me. But I do, after all, wind up with a murder to solve. Several, actually. Though I’m getting ahead of myself.

The point is, I read a lot of crime novels. And I know most of these types of books have what’s known as an ‘unreliable narrator’ these days, where the person telling you the story is, in fact, lying most of the time. I also know that in recounting these events I may be typecast similarly. So I’ll strive to do the opposite. Call me a reliable narrator. Everything I tell you will be the truth, or, at least, the truth as I knew it to be at the time that I thought I knew it. Hold me to that.

This is all in keeping with Knox’s commandments 8 and 9, for I am both Watson and Detective in this book, where I play both writer and sleuth, and so am obligated to both light upon clues and not conceal my thoughts. In short: play fair.

Actually, I’ll prove it. If you’re just here for the gory details, deaths in this book either happen or are reported to have happened on page 14, page 46, page 65, a two-fer on page 75, and a hat-trick on page 81. Then there’s a bit of a stretch but it picks up again on page 174, page 208(ish), page 218, page 227, page 249, somewhere between page 243 and page 250 (it’s hard to tell), page 262, and page 355. I promise that’s the truth, unless the typesetter mucks with the pages. There is only one plot-hole you could drive a truck through. I tend to spoil things. There are no sex scenes.

What else?

My name would be useful, I suppose. I’m Ernest Cunningham. It’s a bit old-fashioned, so people call me Ern or Ernie. I should have started with that, but I promised to be reliable, not competent.

Considering what I’ve told you, it is tricky to know where to start. When I say everyone, let’s draw the line for that statement at my branch of the family tree. Although my cousin Amy did bring a prohibited peanut-butter sandwich to a corporate picnic once and her HR rep almost carked it, but I won’t put her on the bingo card.

Look, we’re not a family of psychopaths. Some of us are good, others are bad, and some just unfortunate. Which one am I? I haven’t figured that out yet. Of course, there’s also the little matter of a serial killer known as the Black Tongue who gets mixed up in all this, and $267,000 in cash, but we’ll get to that. I know you’re probably wondering something else right now. I did say everyone. And I promised no tricks.

Have I killed someone? Yes. I have.

Who was it?

Let’s get started.

Chapter One

A single beam of light rotating through the curtains told me my brother had just pulled into my driveway. When I walked outside, the first thing I noticed was that Michael’s left headlight was out. The second was the blood.

The moon had gone, the sun yet to rise, but even in the dark I knew exactly what the dark spots were, flecked on the shattered headlight and smeared alongside a hefty dent in the wheel arch.

I’m not normally a night owl, but Michael had called me half an hour before. It was one of those phone calls that, as you blearily read the time, you know is not to tell you about winning the lottery. I have a few friends who occasionally call me from their Uber home with a roaring tale of a good night out. Michael is not one of them.

That’s a lie, actually. I wouldn’t be friends with people who called after midnight.

‘I need to see you. Now.’

He was breathing heavily. No call ID, from a pay phone. Or a bar. I spent the next half hour shivering, even in a heavy jacket, wiping circles in the condensation on my front window to better see his approach. I’d given up sentry duty and retired to the couch when his headlight flicked the back of my eyelids red.

I heard a growl as he brought the car to a stop, then killed the engine but not the electrics. I opened my eyes, savoured the ceiling for a moment, as if I knew that once I stood up my life would change, and went outside. Michael was sitting in the car, head on the wheel. I cut the lonely spotlight in half as I walked in front of the bonnet to knock on the driver’s window. Michael got out of the car. His face was ash grey.

‘You’re lucky,’ I said, nodding to his busted headlight. ‘Roos’ll mess you up.’

‘I hit someone.’

‘Uh-huh.’ I was half asleep, so only barely registered he’d said someone and not something. I didn’t know what people said in these situations, so I thought agreeing with him was probably a good idea.

‘A guy. I hit him. He’s in the back.’

I was awake now. In the back?

‘What the hell do you mean in the back?’ I said.

‘He’s dead.’

‘Is he in the back seat or the boot?’

‘Why’s it matter?’

‘Have you been drinking?’

‘Not much.’ He hesitated. ‘Maybe. A bit.’

‘Back seat?’ I took a step and reached out for the door, but Michael put an arm out. I stopped moving, said, ‘We need to take him to the hospital.’

‘He’s dead.’

‘I can’t believe we’re arguing about this.’ I ran a hand through my hair. ‘Michael, come on. You’re sure?’

‘No hospital. His neck turned like a pipe. Half his skull is inside out.’

‘I’d rather hear it from a doctor. We can call Sof—’‘Lucy will know,’ Michael cut me off. His mention of her name, said so desperately, made the subtext clear: Lucy will leave me.

‘It’ll be all right.’

‘I’ve been drinking.’

‘Just a bit,’ I reminded him.

‘Yeah.’ The pause lingered. ‘Just a bit.’

‘I’m sure the police will under . . .’ I started, but we both knew the name Cunningham said aloud in a police station practically shook the walls with the spirits it summoned. The last time either of us had been in a room full of cops was at the funeral, among a sea of blue uniforms. I’d been tall enough to coil myself around my mother’s forearm, but young enough to stay glued there all day. I briefly imagined what Audrey would think of us now, huddled in the freezing morning arguing over someone’s life, but pushed the thought away.

‘He’s not dead because I hit him. Someone shot him, then I hit him.’

‘Uh-huh.’ I tried to sound like I believed him, but there’s a reason my dramatic résumé consisted mostly of non-speaking roles in school plays: farm animals; murder victims; shrubbery. I went for the door handle again, but Michael kept it blocked.

‘I just grabbed him. I thought – I don’t know, it was better than leaving him in the street. And then I couldn’t think what to do next, and I wound up here.’

I didn’t say anything, just nodded. Family is gravity.

Michael rubbed his hands across his mouth and spoke through them. The steering wheel had left a small red dent on his forehead. ‘It’s not going to matter where we take him,’ he said at last.

‘Okay.’

‘We should bury him.’

‘Okay.’

‘Stop saying that.’

‘All right.’

‘I meant stop agreeing with me.’

‘We should take him to the hospital then.’

‘Are you on my side or not?’ Michael glanced towards the back seat, got back in the car and turned the engine on. ‘I’ll fix things. Get in.’

I already knew I’d get in the car. I don’t really know why. Part of me figured that if I was in the car I could talk some sense in to him, I guess. But all I really knew was that my older brother was standing in front of me, telling me it would all be all right, and it doesn’t matter how old you get – five or thirty-five – if your older brother tells you he’s going to fix things, you believe him. Gravity.

Just quickly: I’m actually thirty-eight in this bit, forty-one when we catch up to the present day, but I thought if I shaved a couple of years off it might help my publisher pitch this to a big-name actor.

I got in. There was a Nike sports bag, unzipped, in the footwell of the passenger seat. It was stuffed with cash, not tied together with neat little elastic bands or paper belts like in the movies, but jumbled up, vomiting onto the floor. It felt strange to simply rest my feet on it, because there was so much of it and, assumedly, the man in the back seat had died for it. I didn’t look in the rear-view mirror. Okay, I shot a few glances, but I only saw a black lump of a shadow that looked more like a hole in the world than an actual body, and I wussed out every time it threatened to come into focus.

Michael backed out of the drive. A shot glass or something rattled across the dash, fell and rolled under the seat. There was a faint waft of whiskey. For once, I was glad my brother was into hotboxing, because the weed smoke lingering in the upholstery masked the smell of death. The boot clanged, latch broken, as we bounced over the kerb.

A horrible thought shot through me. He had a shattered headlight and a busted trunk: like he’d hit something twice.

‘Where are we going?’ I asked.

‘Huh?’

‘Do you know where you’re going?’

‘Oh. The national park. Forest.’ Michael looked across at me, but couldn’t hold my gaze, so he threw a furtive look to the back seat, apparently regretted it, and settled on staring forwards. He’d started to shake. ‘I don’t really know. I’ve never buried a body before.’

We’d driven for over two hours by the time Michael decided he’d taken enough dirt roads and pulled his rumbling cyclops of a car into a clearing. We’d hopped off a fire trail a few kilometres back and wound our way off road since. The sun was threatening to rise. The ground was covered in glittering, soft snow.

‘Here’ll do,’ said Michael. ‘You okay?’

I nodded. Or at least I thought I did. I mustn’t have moved at all, because Michael snapped his fingers in front of my face, forcing me to focus. I summoned the weakest nod in human history, as if my vertebrae were rusted shackles. It was enough for Michael.

‘Don’t get out,’ he said.

I stared straight ahead. I heard him open the back passenger door and shuffle around, dragging the man – a hole in the world – out of the car. My brain was screaming at me to do something, but my body was a traitor. I couldn’t move.

After a few minutes Michael came back, sweating, dirt on his forehead, and leaned in over the steering wheel. ‘Come help me dig.’

My limbs unlocked at his bidding. I expected the ground to be cold, to hear the crunch of morning ice, but my foot instead went straight through the white cover, up to my ankle. I looked closely. The ground wasn’t snow coated, it was blanketed in spider webs. The webs were strung between high stiff grass, maybe a foot off the ground, crossing over each other in such a thickness and with such a pure white, it looked solid. What I had thought was glittering ice was the twinkle of fine threads in the light. Michael’s footsteps had punched through the net like holes in powder. The webs covered the entire clearing. It was majestic, serene. I tried to ignore the lumpy shape in the middle of the webbed clearing, where Michael’s footprints ended. I followed Michael, and it was like wading through a levitating fog. He led me away from the body, presumably so I wouldn’t have a breakdown.

Michael had a small trowel but he made me use my hands. I don’t know why I agreed to dig. The whole drive, I’d thought that Michael’s fear, that small dose of shakes he’d shown when we’d left, would settle in. There was supposed to be a moment when he would realise what he was up to his neck in and turn the car around. But instead he went the other way. Driving out of the city, into the dawn, he’d become calmer, stoic.

Michael had laid an old towel over most of the body, but I could see a white elbow, sticking out like a fallen branch above the webs.

‘Don’t look,’ Michael would say whenever I glanced over.

We kept going for another fifteen minutes in silence until I stopped.

‘Keep digging,’ Michael said.

‘He’s moving.’

‘What?’

‘He’s moving! Look. Wait.’

Sure enough, the webbed surface was twitching. More significant than wind through the clearing. The impression had changed from solid snow to a rippling white ocean. I could almost feel it through the threads, like I was the spider that spun it, the central nerve.

Michael stopped digging and looked up. ‘Go back to the car.’

‘No.’

Michael walked over and peeled off the towel. I followed, and saw the body in full for the first time. There was a dark glistening stain above one hip. Someone shot him, then I hit him, Michael had said. I wasn’t sure; I’d only seen gunshots in the movies. The man’s neck had a lump in it as if he’d swallowed a golf ball. He was wearing a black balaclava, but it wasn’t quite the right shape. The fabric was bulbous in the wrong places. When I was a kid, a bully at my school used to put two cricket balls in a sock and swing it at me. That’s what the balaclava looked like. I got the feeling the fabric was the only thing holding his head together. It had three holes, two for the eyes, which were closed, and one for the mouth. There were small red bubbles pooled on his lips, pulsing. The froth of bubbles was growing, spilling onto his chin. I couldn’t see any of his features, but I could tell from his mottled, sun-damaged arms and the engorged veins across the backs of his hands that he was at least twenty years older than Michael.

I knelt, interlocked my hands, and gave a couple of rudimentary compressions. The man’s chest caved in a way I knew it shouldn’t, right down the sternum, and for a moment all I could think of was that his chest was like the bag of money, unzipped down the middle.

‘You’re hurting him,’ Michael said, putting his hand under my arm and pulling me up, before guiding me away.

‘We have to take him to the hospital.’ I made one last, pleading stand.

‘He won’t make it.’

‘He might.’

‘He won’t.’

‘We have to try.’

‘I can’t go to the hospital.’

‘Lucy will understand.’

‘No.’

‘You must have sobered up by now.’

‘Maybe.’

‘You didn’t kill him – you said he was shot. Is the money his?’

Michael grunted.

‘He clearly stole it. This makes sense. You’ll be okay.’

‘It’s two hundred and sixty grand.’

Reader, you and I already know it’s actually two hundred and sixty-seven grand, but it still struck me that while he hadn’t had time to call an ambulance, he’d had time to roughly count the cash. Otherwise he’d have said two-fifty, a round figure, if he was guessing. He’d also said it like an appeal. I couldn’t tell from his tone if he was offering me any, or if he was just stating a fact that he thought was important to the decision.

‘Listen, Ern, it’s our money . . .’ he started to beg. So he was offering.

‘We can’t just leave him here like this.’ And then as firmly as I’d ever spoken to him in my life, ‘I won’t.’

Michael thought for a minute. Nodded. ‘I’ll go check on him,’ he said.

He walked over and crouched by the body. He was there a couple of minutes. I was glad I’d come; I still believe it was a good thing to do. An older brother doesn’t listen too easily to his younger brother, but he’d needed me here. And I’d made it okay. The man had been alive the whole time, and we’d get him to the hospital. I couldn’t see much, Michael being tall, but I could see his squatted back and his arms, stretched out towards the man’s head because he knew to cradle the neck in case of a spinal injury. Michael’s thin shoulders moved up and down. CPR, kick-starting the man like a lawnmower. I could see the man’s legs. I noticed one of his shoes was missing. Michael had been there a long time now. Something was wrong. We’re on page 14.

Michael stood and walked back over to me. ‘We can bury him now.’

That wasn’t what he was supposed to say. No. No. That was all wrong. I stumbled back and thumped onto my arse. Sticky threads snaked my arms.

‘What happened?’

‘He just stopped breathing.’

‘He just stopped breathing?’

‘He just stopped.’

‘He’s dead?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘How?’

‘He just stopped breathing. Go wait in the car.’