By Stafford Sanders. The latest from A Sense of Place Publishing.

“Halloran!” barked Bascombe as we drew up in front of the stables. There was no immediate response to this, so he repeated more loudly:

“Halloran!” And for good measure, “Get your lazy bog-Irish arse out here at once!”

At this pleasant imprecation, a rather pot-bellied fellow of indeterminately middle age, dressed in shabby arrow-headed garb, emerged from the stables – prattling in an almost theatrical Irish brogue like some captured pantomime leprechaun about to grant a wish: “Here I am, sir, at your service. Sure an’ it’s a lovely mornin’! What can I be doin’ for you two good gentlemen?”

“Cut the paddy palaver, Halloran,” snapped the Major. “Dr Quayle here” (with a perfunctory nod at me) “is our new colonial surgeon. He’ll be needing a horse. A good one, mind, not your usual nags.”

“Ah, delighted to meet you, doctor,” said the smiling stablehand, turning towards me. At once I felt that the crinkled, weatherworn visage and the jovial Irish accent were somewhat familiar. I looked at him more closely as he grinned and gestured, his pupils darting about like deranged mosquitoes trying to escape from his head, his genial patter rattling onward:

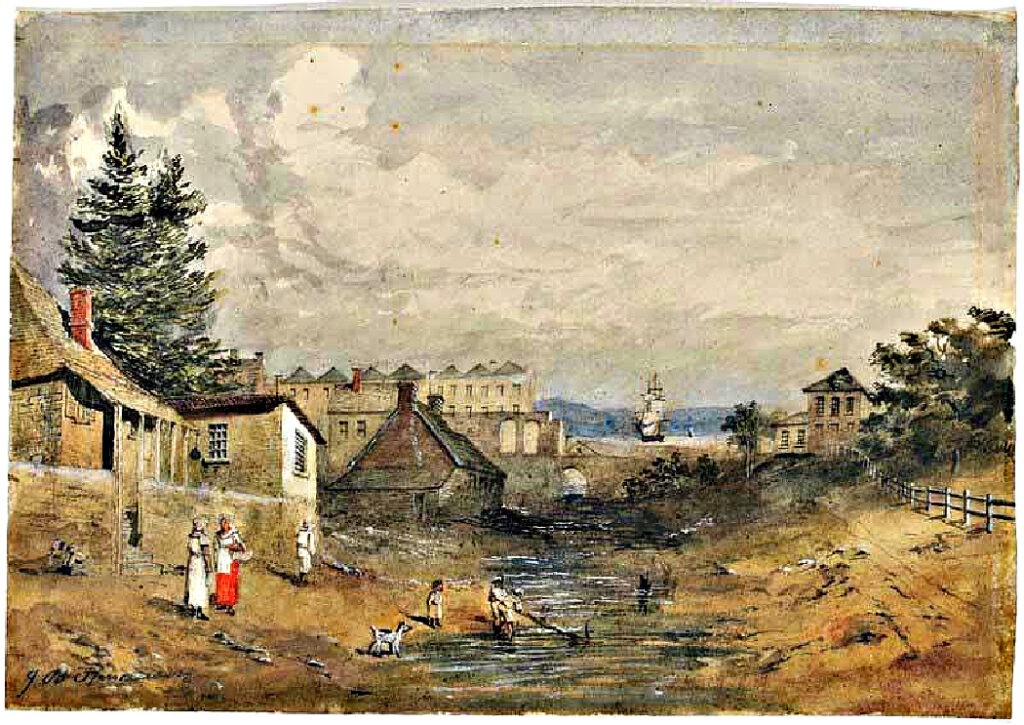

“Welcome to Port Fortitude. I’ll be gettin’ you saddled up then, sir – since I am as you might say, saddled with that responsibility (ha ha)!” His mobile, fleshy face creased readily into an enormous grin as he chuckled at his own rather weak jape.

Bascombe, clearly at the end of his patience – which, it could be assumed, did not extend far at the best of times with regard to this Irishman – rolled his eyes and snarled icily at him: “Shut up and get on with it.”

“Right you are, sir.” The stablehand, having decided he had pushed the cheery prattle as far as he dared, bowed his head and turned to obey – but I stopped him, now remembering more definitely the moment of my arrival upon the beach and the encounter with the arrowhead-garbed fellow under the straw hat.

“I say… haven’t we already met?”

He turned to me with a look of convincing bewilderment, blinking like a startled animal caught in the beam of a lantern. “I… don’t believe I’ve had the pleasure, sir.”

“I left my trunk in your care, didn’t I?”

His response came like lightning, the eyes barely flickering. “Us convicts all look the same, sir. It’s the tailorin’.” A wink and another chuckle at this – but it was immediately transformed into a startled cry and a gasp for breath, as Bascombe stepped forward, seized him roughly by the shirt collar and twisted it, raising the poor fellow onto his tip-toes.

“You thieving scoundrel!” growled the Major. “What have you done with the doctor’s trunk?”

“It wasn’t me, sir,” squawked the convict, dangling like a portly marionette, his feet scraping dustily for purchase. “I was never down at the beach this mornin’.”

“We’ll soon find out,” snarled Bascombe with venom. “A good flogging ought to get the truth out of him.” At this, the Major released his hold on the stablehand, who slumped wheezing and gasping to the ground. “I’ll have it arranged right away. Nothing a few strokes of the lash won’t….”

Perhaps it was the prospect of having to witness another of those dreadful spectacles, and worse, to attend to its gory aftermath. In any case, the immediate churning in my vitals propelled me toward immediate interruption. Certainly there was more gut than brains in the decision.

“No!” I blurted.

There was a moment’s pause. Bascombe turned to me, teeth clenched. “What?”

“It… wasn’t him,” I said, less than convincingly. The Major certainly did not appear convinced – indeed he stood with mouth agape, apparently unable to believe his ears, merely repeating: “What are you saying?”

“I was… mistaken”, I persisted. “The man on the beach was… was much taller. And…” I was thinking quickly now, “… he, er… walked with a pronounced limp.”

Bascombe considered this for an instant, eyes narrowed. “From what you told me, he never moved. Standing against a post, you said.”

“Well, he er…he… stood with a limp.” I smiled weakly at him, appalled that this was the best I could come up with.

The Major took a deep breath, then grasped my arm firmly and led me aside, growling in a stage whisper: “Listen, don’t let these people get the better of you, Doctor. I keep telling the Governor – too much of this soft treatment, this ‘rehabilitation’ he goes on about, and they’ll be murdering us in our beds…”

“This isn’t the man,” I repeated simply and stubbornly, meeting his gaze as directly as I could manage.

Bascombe looked positively fierce, his prominent chin quivering intensely. I almost imagined he was about to seize me by the scruff of the neck and dangle me aloft in the same brutal manner as he had manhandled the hated Irishman. After a moment, however, he appeared to suppress his rage, released my arm with a contemptuous sniff, and said very quietly:

“As you wish, doctor. Be it on your own head. I’ll see you back at the barracks.” And after a last hateful grimace at the still-seated ticket-of-leaver who had so heinously escaped his just punishment for yet another undetected crime, the Major turned on his heel and strode grimly off towards the barracks compound, a cloud of dust trailing behind him.

I turned and extended my hand towards the half-prostrate Halloran, who took it and allowed me to assist him shakily to his feet.

“Thank you very kindly, Your Doctorship,” he said meekly, making a rudimentary effort at dusting himself off while rubbing his chafed neck. “I’m most grateful to you.”

“Well,” I responded, not wishing to appear too easy a mark, “I’d be grateful to get my trunk back.” I looked at him sternly.

He appeared chastened, responding earnestly: “I’ll move heaven and earth to see that it… er, turns up, sir.”

“As long as it ‘turns up’ by no later than tomorrow, I shall say no more.”

May 31, 2021 at 12:20 am

Very inspired ! Bravo My friend! this is the best post I’ve ever read, may I know you better?

July 14, 2021 at 7:18 pm

Nice Article.

Thank you

Visit Us

http://www.ittelkom-sby.ac.id