The pain of America’s endless wars linger long after the generals and opportunists and political grifters depart the battlefield.

Vietnam is the classic example.

No one even bothers to pretend that the war was morally or strategically justified in any sense; that it was not built on a lie, that it did not do enormous damage to America’s reputation, or that the suffering inflicted on millions of people was not the result of the corruption of the American military establishment, its so-called military industrial complex.

More than 58,000 American soldiers died in that terrible war; and 523 Australians. Many other Vietnamese veterans suffer to this very day.

They died for what?

These days Vietnam’s population displays far more national pride, and the country is more socially cohesive, economically prosperous, and better respected on the world stage than either America or Australia.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the last American soldier to leave Vietnam. A terrible sorrow; and a triumph of the human spirit.

The Long Reckoning

The moving story of how a small group of people—including two Vietnam veterans—forced the U.S. government to take responsibility for the ongoing horrors—agent orange and unexploded munitions—inflicted on the Vietnamese.

“Fifty years after the last U.S. service member left Vietnam, the scars of that war remain…This [is the] remarkable story of a group of individuals determined to heal those enduring wounds.”—Elliot Ackerman, author of The Fifth Act and 2034

The American war in Vietnam has left many long-lasting scars that have not yet been sufficiently examined. The worst of them were inflicted in a tiny area bounded by the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail in neighboring Laos. That small region saw the most intense aerial bombing campaign in history, the massive use of toxic chemicals, and the heaviest casualties on both sides.

In The Long Reckoning, George Black recounts the inspirational story of the small cast of characters—veterans, scientists, and Quaker-inspired pacifists, and their Vietnamese partners—who used their moral authority, scientific and political ingenuity, and sheer persistence to attempt to heal the horrors that were left in the wake of the military engagement in Southeast Asia.

Below is an extract from the essay Agent Orange: The Cleanup Begins by John Stapleton. It was originally written in 2012.

On the morning of the 9 August 2012, Americans in particular but people around the world were astonished to observe an historic event occurring at busy Da Nang airport in Vietnam. The lingering impacts of the infamous herbicide Agent Orange were finally to be addressed, 37 years after the end of the Vietnam War.

Da Nang was one of the three worst spots for dioxin contamination in the whole of Vietnam. It was one of the major sites where American soldiers decanted, mixed and re-loaded ton after ton of the herbicide transported to Vietnam during the early 1970s.

Agent Orange was then sprayed across the country’s lush valleys, fields and forests.

The former American military base at Da Nang was in a sparsely populated rural area outside a village at the time of the Vietnam War, which ended amidst chaotic scenes in 1975.

Now in the heart of an urban area, Da Nang is extremely popular with both Vietnamese and foreign tourists.

The generation which grew up with peace demonstrations dividing their country now has the money to pursue their fascination with the first war to be played out on television before an audience of millions.

Many former Vietnam veterans travel to Vietnam to seek out the places where they served. By the end of the war American forces had utilized a total of 2,735 bases, although the remains of these for the most part can no longer to be seen.

Between 2012 and 2016 some 77,400 cubic metres of soil, 2.7 million cubic feet, are scheduled to be dug up from the Da Nang Airport and treated.

The treatment involves heating the contaminated soil to a minimum temperature of 325 degrees centigrade, the temperature at which dioxin breaks down into harmless compounds.

The soil is then repeatedly tested until dioxin levels are negligible and it is then re-interred.

Dioxin is regarded as one of the most toxic, if not the single most toxic, of all the compounds ever synthesized by man.

It is dangerous at even “vanishing levels” – 10 parts per trillion or more. It is tested for in parts per quadrillion, an exercise compared to finding a coffee cup in Canada.

The technical capacity to do this accurately did not exist for some 20 years after the Vietnam War.

Seven parts per trillion, that is seven molecules of dioxin in an Olympic sized swimming pool, are believed to be the threshold level above which the probability of shortened life spans and birth defects increases.

The Vietnamese Red Cross estimates that around three million of their countrymen are suffering from the impacts of Agent Orange, with around 150,000 children born with birth defects.

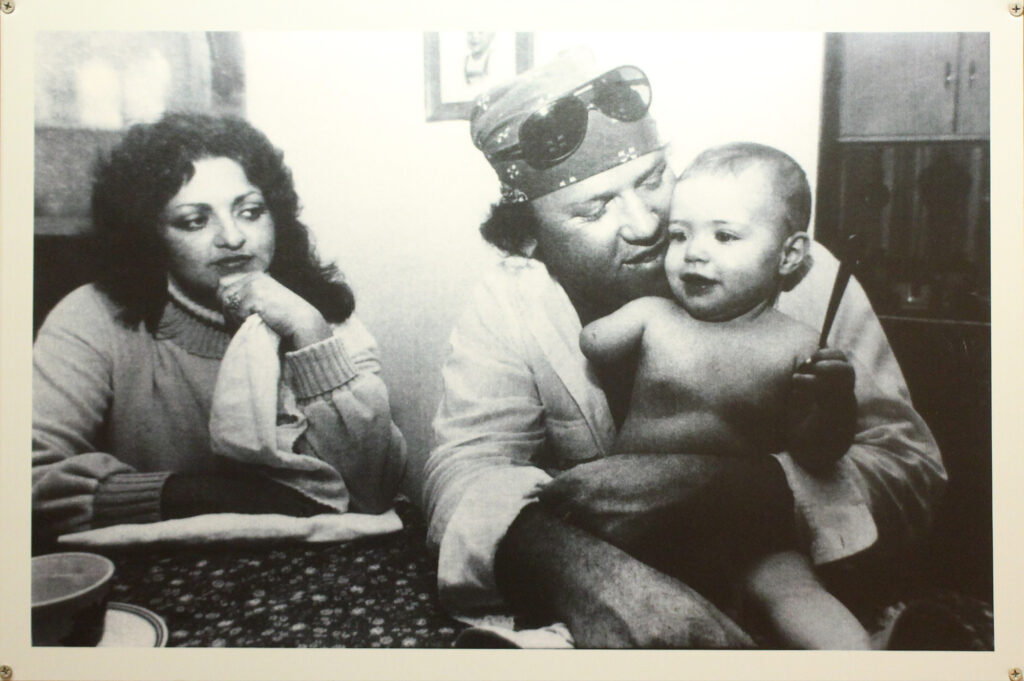

As well thousands of American veterans and their families have been affected, as well as veterans from other countries which participated in the Vietnam War, including Australia.

While the science remains disputed, Dioxin is widely believed to have inter-generational effects.

Although dioxin is not water soluble, it can persist in soil for decades and this persistence increases the probability it will at some point move into nearby streambeds and pond bottoms and from there be taken up by fish, ducks, snails and thereby enter the food chain.

Many of those born with birth defects were born well after the close of the Vietnam War. Their parents were not participants in the conflict nor were they in the direct path of the spraying. Instead both mothers and fathers came to have high dioxin levels in their bloodstreams by consuming contaminated foods or by working in areas where there were high residue levels. Or by swimming in lakes and canals where the toxin had settled into silt.

Transporting the soil from Da Nang Airport to be buried in another location was dismissed as an unviable option.

Its transportation would have endangered workers and its burial imperilled future generations if it were ever exposed by seismic or mining activity.

As Da Nang Airport is operational, gaping holes in the tarmac would have also invoked additional costs.

Among the 18 commercially available technologies to destroy dioxin a number use heating soil as the means to break down the dioxin molecules. The particular technology the American and Vietnamese governments agreed to use at Da Nang is known as In-pile Thermal Desorption.

In front of a gathering of dignitaries from both America and Vietnam, the amelioration efforts to destroy the dioxin remaining in the Vietnamese environment and to treat those suffering from disabilities began.

The project is being run under the auspices of the Vietnamese Ministry of Defence and the United States Agency for International Development.

The U.S. Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange/Dioxin is a bi-national advocacy committee of private citizens, scientists and policy-makers working to draw greater attention to the issues and to mobilise resources in both countries. The Group has estimated the cost of cleaning up all the Agent Orange hotspots in Vietnam and providing substantial health and disability programs at $450 million.

The United States Government had not, as of October 2012, agreed to do more on than the environmental remediation than what they plan to do at Da Nang, costing $43 million over the four year operation, and an Environmental Impact Assessment at Bien Hoa north of Ho Chi Minh City. The U.S. has also announced plans for a three year $9 million health and disabilities program mainly directed to Da Nang.

Three studies conducted between 2004 and 2010 have confirmed high levels of contamination of dioxins in soils and sediments at a number of locations on Bien Hoa Airbase, making the site a significant dioxin hotspot.

In 1970 a 7,500 US gallon spill of Agent Orange occurred at the air base.

The clean-up of dioxin at Bien Hoa is estimated to cost $US85 million, almost twice the cost of Da Nang.

Bien Hoa was the largest site in Vietnam in terms of the number of C-123 aircraft sorties and volume of herbicides used.

Dioxin contamination at Bien Hoa Airbase is the result of the storage, loading, spillage, and handling of Agent Orange and other herbicides, especially between 1965 and 1971.

Interim mitigation measures are currently being implemented at Bien Hoa to protect the local population from continued exposure to dioxins from the Airbase. Approximately 43,000 cubic metres of contaminated soils have been excavated and placed in a secure landfill by the Vietnamese Ministry of Defence. This work was completed in 2009.

A third serious dioxin hotspot lies at the coastal city of Phu Cat. The Ministry of Defence, UNDP and the Global Environmental Fund have collaborated on moving the 7,500 cubic meters of contaminated soil into a long term passive landfill on the base. The landfill will be monitored and maintained by the Ministry with technical support from the Czech Republic. The Government of Vietnam in August removed Phu Cat from the list of dioxin hotspots.

With the passage of time the former American military base of Bien Hoa is now located in a heavily populated district.

Over 900,000 people reside in the Bien Hoa area. Many of these local people have the potential to be exposed to dioxin residues.

Another $410 million needs to be raised to resolve Vietnam’s Agent Orange issues.

The Dialogue Group estimates that a total of $US107 million will be required for the cleanup of dioxin hotspots, including $US17 million to evaluate and clean up as needed about two dozen smaller known or suspected dioxin hotspots.

A further $US303 million is required for the provision of social and disability services.

But after decades of painfully slow progress developments have sped up significantly.

On June 16, 2010 the Dialogue Group published a ten year Declaration and Plan of Action to address the continuing environmental and human consequences of Agent Orange. In May 2012 the U.S. Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange released its Second Year Report simultaneously in Washington and Hanoi.

The introduction noted: “It should not surprise us that only now, nearly 40 years after the end of hostilities, are we on the cusp of resolving one of the troubling legacies of the war between the US and Vietnam — the lasting effects of Agent Orange and other dioxin-contaminated defoliants on people, communities and ecosystems in Vietnam.

Wars leave raw political and emotional wounds.

Enduring concerns are poorly understood, and by definition, former enemies lack the trust and experience of collaboration on which a new strategic partnership can be built. The Vietnam-US relationship illustrates this truth all too clearly. It most likely holds lessons for other wars about the time that must pass before painful legacies can be fully resolved.

“And indeed, for decades little could be done about Agent Orange/dioxin. The science about its biological and ecological impacts was poorly understood. So was the extent of the problem; dioxin’s impact on US military personnel was contentious in the United States. And litigation in US courts on behalf of those in Vietnam who believed themselves to be victims brought fresh legal battles, controversy and wariness.

“But in the last five years, much has changed, in significant measure because of creative and compassionate interventions by public and private agencies. The concerns of US veterans are being addressed far more comprehensively than in past decades – though continued attention is needed.

“Lawsuits have slowed. The geography of the dioxin ‘hot spots’ in Vietnam is clear, along with estimates of clean-up costs. A remarkable start has been made towards cleaning up the first of the three major hot spots at the Da Nang airport. Rough estimates of the number of people with disabilities that may be linked to dioxin are available. Their needs – and those of their caregivers – are better understood. The cost and complexity of clean-up and care can now be estimated based on real lived experience.”

The Vietnamese Government has set the year 2020 as the target for completion of the work on cleaning up Agent Orange under a National Action Plan.

As it is impossible to determine which people are suffering disability as a direct result of Agent Orange or to differentiate them from those disabled through other causes, the money would be spent in a broadcast way by addressing the needs of all people with disabilities living in the vicinity of identified hot spots and in areas heavily sprayed during the war.

The Da Nang phase of the cleanup is not expected to be complete until 2016.

Da Nang is the starting point, not the end point.

There are some 25 to 27 further locations to be assessed, where dioxin is known or suspected to exist, albeit at significantly lower levels than at Da Nang, Phu Cat or Bien Hoa.

Vietnamese experts suspect that there are a few areas in Vietnam where the dioxin has pooled in the sediment of upland ponds and reservoirs in heavily sprayed regions. According to the Forestry Inventory and Planning Institute (FIPI) analysis conducted in 2010, Bien Phuoc, Dong Nai, Quang Nam, Thua Thien Hue and Tay Ninh all have reservoirs in the sprayed regions.

Some of the regions sprayed had large areas of rivers and ponds.Proponents for resolving the Agent Orange legacy are hopeful USAID will now step in with funding and expertise to help complete the assessment of all suspected hotspots and the clean-up of dioxin in those remaining locations where dioxin exceeds acceptable levels.

The infamous Agent Orange was named after the colour of the striped 55 US gallon barrels in which the herbicide was shipped.

It was the most widely used of the so-called “Rainbow Herbicides” or defoliants sprayed across Vietnam. There were also Agents Pink, Blue, Purple, Green and White.

Agents Pink, Green and Purple were all contaminated with dioxin.

A team of scientists at Columbia University have estimated that at least 366 kilograms of dioxin were sprayed across Vietnam, with some estimates placing it at 600 kilograms.

A large bull is led to the stadium at the Buffalo Fighting Festival in Do Son, Vietnam.

Nobody at the time realised just how dangerous the herbicide Agent Orange, or more precisely its contaminant dioxin, was. In a rush to meet the demands of the war effort in South East Asia, there was little if any concern by manufacturers or the soldiers doing the spraying of the danger Agent Orange represented.

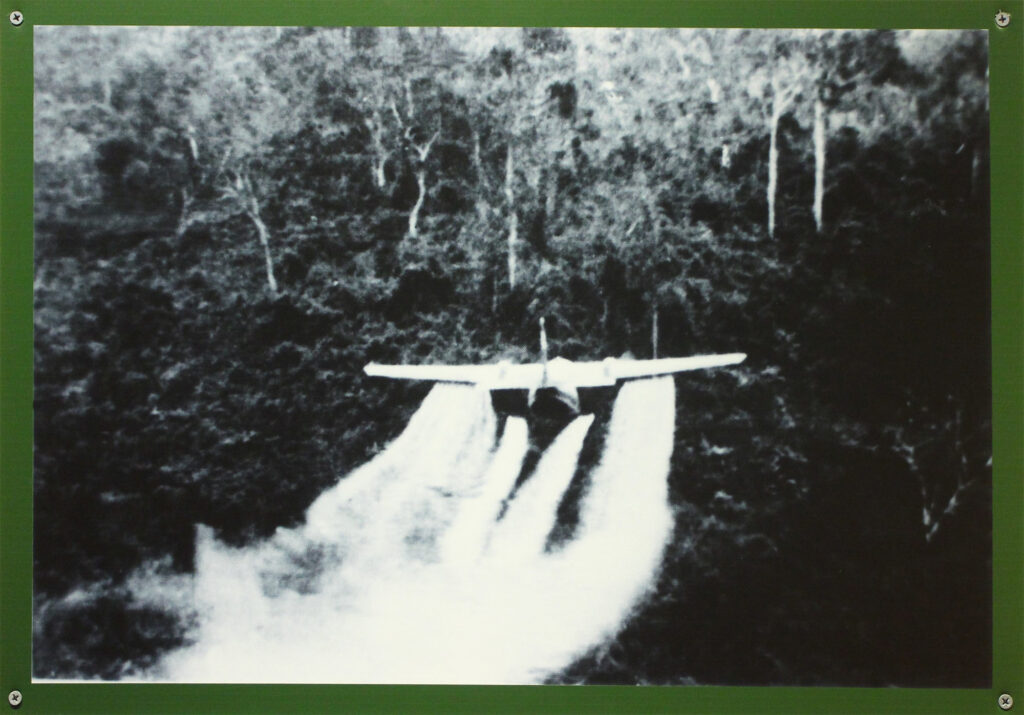

Agent Orange was conducted under a program called Operation Ranch Hand, which in turn was part of the broader spraying program called Operation Trail Dust. The program took place from January 1962 until February 1971.

In total, some 20 million US gallons of defoliant were sprayed from some 20,000 sorties.

The motto of Ranch Handers was: “Only you can prevent a forest”.

This was a play on the anti-bushfire slogans plastered across the US Forestry’s Smokey Bear posters of the time.

Some 95 per cent of the herbicides were sprayed from the giant US cargo planes known as C-123s. Their call sign was “Hades” from the Greek word for hell or the underworld, the abode of the dead. The U.S. Chemical Corps and other allied forces sprayed the remaining five per cent of the herbicides from helicopters, trucks and by hand, mainly to clear brush around the perimeter of military bases.

The painful story of neglect and obfuscation surrounding the impacts of the herbicide Agent Orange begins in 1961.

In the long lead up to the War, the first test spraying of Agent Orange occurred on August 10 of that year, well before the Vietnam War’s official beginning with the deployment of combat troops in 1965.

In Vietnam August 10 has now been declared Agent Orange Day.

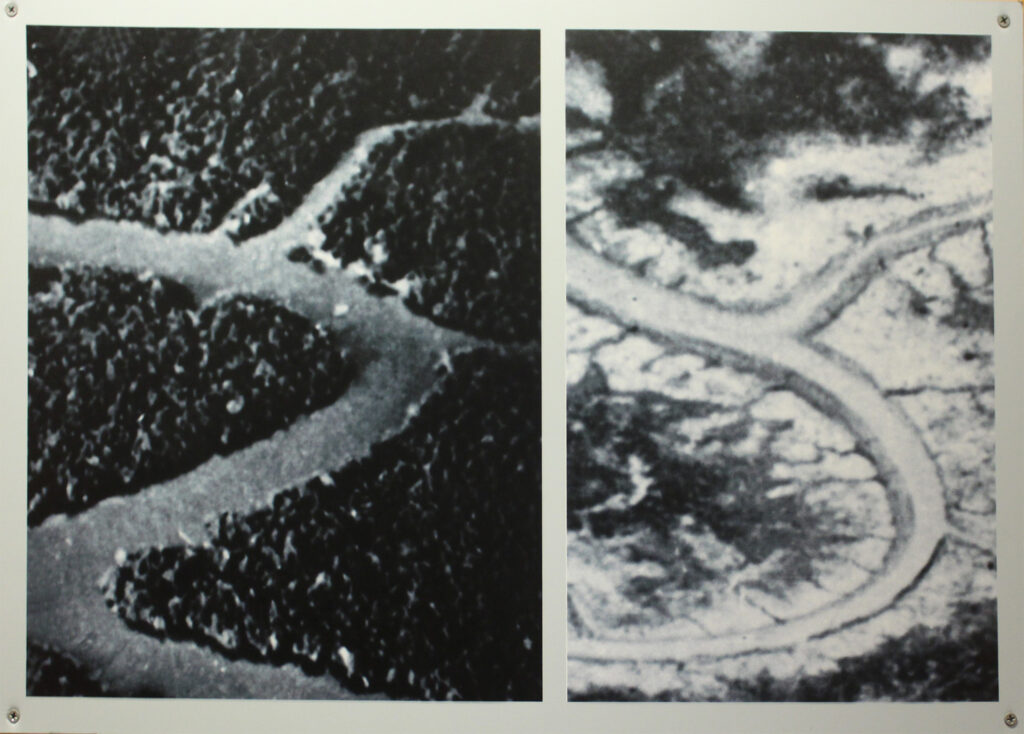

In the years following 1962 more than 43 million litres of Agent Orange was sprayed at up to 50 times the manufacturer’s recommended levels across 24 percent of southern Vietnam. Some five million acres of upland and mangrove forests and about 500,000 acres of crops were destroyed.

Of this area, 34 percent were sprayed more than once; some of the upland-forests were sprayed more than four times. The aim was to deny the enemy both cover and food sources.

One studied found that 3,138 villages were in the path of the spray.

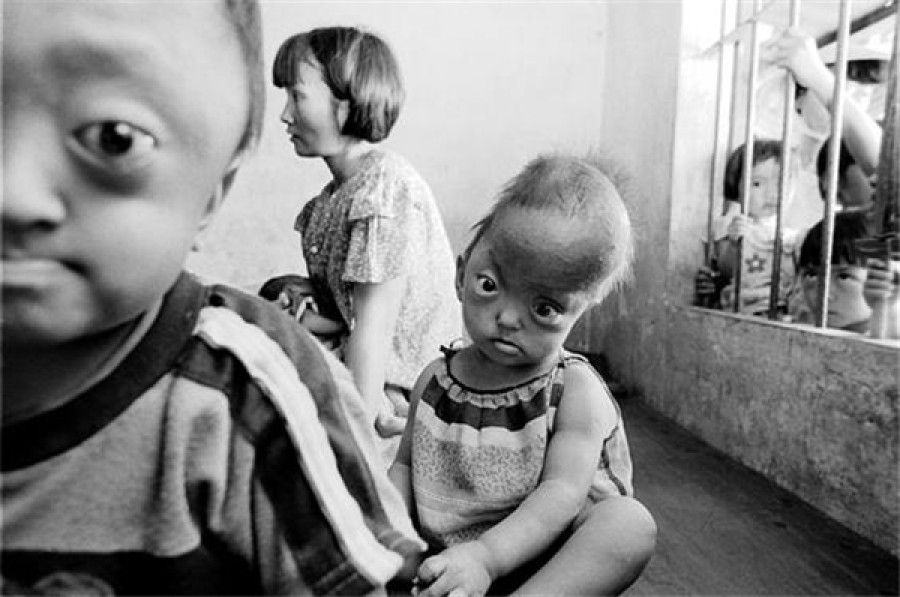

Severely disabled and abandoned at birth, 124 children live at the Ba Vi Orphanage and Elderly Home near Hanoi, Vietnam. They are believed to be third-generation victims of Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War.

Nothing is known about these children’s family histories and the center lacks the resources to conduct medical tests to prove such a link. To care for them, there is one doctor, two nurses, and six caretakers. Eighty percent of them are mentally disabled. Most of the children who live here have no recreation, education or physical therapy; they spend the majority of their days in wooden chairs or in mass beds. Some children are prone to wandering off at night or harming the other children so they are locked in iron cages overnight and during afternoon naps. For the majority of these children, this is the only home they will ever know.

Parts of Laos and Cambodia near the Vietnam border were also sprayed.

The Americans ceased spraying Agent Orange in October, 1971, following concern over its side effects on the environment and studies demonstrating its carcinogenic effects. But the South Vietnamese military continued spraying various herbicides until 1972.

All the remaining barrels of the herbicide were shipped out of the country and destroyed. The production of Agent Orange was ended in the 1970s and remaining stockpiles incinerated. It is no longer produced.