Michael Gray Griffith: Café Locked out

The station was so vast and remote that chances are the bull had never seen a fence or a house. Now in his prime, he was the king of this harsh terrain—a king who took his freedom for granted, unaware that, somewhere, he was known by another species, us, as livestock.

When he finally met man, he was fighting three four-wheel-drive buggies, each wrapped in bull bars, all striving for the trophy of running him over.

The buggy I was in was the winner. Still holding my camera, and full of the adrenaline my ancestors must have felt on a hunt, I filmed the cattle muster roping his legs together. He, with most of his great shoulders and head pinned under the buggy, in rage and confusion, trying to make sense of what was happening.

The last time I saw him, he was lying on his side, struggling to get up—a fight he would never win. As the cowboys returned to mustering other cattle, he would lay there under the full, unforgiving sun, a gift to the flies and the ants, until the stars returned to look at him one more time.

In the morning, they would return with a truck and, after dragging him into the rear, he’d be off to the meatworks, en route to your plate.

Luke, the musterer, was a man working these remote stations because he was required to be jabbed to work elsewhere. He explained that the station owner wanted these scrub bulls removed to prevent them from breeding with his cows. If the king did, the resulting bulls and cows would be too hard to handle. They would inherit the seeds of hope so precious to them that they’d have the audacity to fight for their freedom.

Instead, the owner brought in a beautiful Brahma bull. Despite his noble appearance, he had been bred to be passive. His offspring would walk into their final pen, where the trucks waited, without so much as a whimper.

I witnessed this.

Back at the farmhouse, I watched these cowboys being tender with the farm cats. Why? Were these bad men pretending, via a purring cat, to be good men? Or were they good men with a job to do—men who had bills to pay?

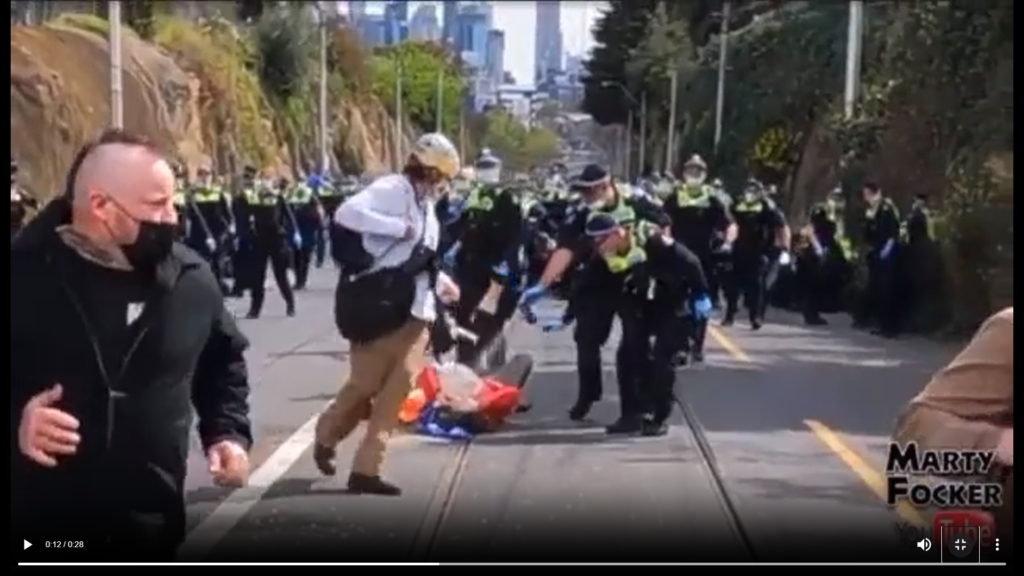

Mary was in her seventies. Despite being born in communist Croatia, she wore the flag of her adopted nation—our flag—like a cape. She had come to the protest in Richmond to see what was going on. What she didn’t know was that, by defending freedom in her own way, she was seen by the state, and its police force, as a scrub bull—a spreader of hope that had to be dealt with.

She became famous when a Victorian police officer shoved her to the ground and pepper-sprayed her. His colleague, another officer, sprayed her too.

As I write this, I wonder: Do these officers have pets? Maybe a dog? Did they pat them or take them for a run that evening as we all waited to hear if she had survived?

The state would go on to lie, claiming Mary was a man dressed in disguise. To our knowledge, neither police officer ever faced charges. Why should they? They had completed their mission: to scare all the other cows back into their Victorian abodes and keep them locked down.

For the last few days, I’ve been in Mildura, and there are scrub bulls here—people who defied the mandates. They’ve learned the lessons of the last few years and now talk online, in chat groups, or quietly to with each other.

A few brave ones spoke to us, but most shyed away from the camera. “Cowed” is the correct word.

Instead, they told me stories of the carnage: friends and family dying of sudden heart attacks and turbo cancers. Friends who, nearing death, would only admit they suspected the jabs were to blame.

But we are not scrub bulls, for we are not livestock—unless we volunteer to act as though we are. What we are is unique slivers of the divine, each a possible hope for all of humanity. But that hope can only be seen if we allow it to shine. The best way for it to shine is to speak.

Michael Gray Griffith of Café Locked out is one of Australia’s leading social documenters of this remarkable period in our history.

He faced a ten year ban on Facebook, no doubt in collaboration with the Australian government, as a direct result of telling the truth.

You can follow his exceptional work on his Substack page here.

You can follow the Marty Focker’s footage of one of the most disgraceful moments of authoritarian abuse in Australian history on YouTube here.