By Alice Gorman, Flinders University

Sixty years ago, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to travel in space when he completed his historic orbit of Earth on April 12, 1961.

It was an extraordinary achievement, but created a dilemma for a world embroiled in the Cold War. Gagarin’s spaceflight heralded a vision of a unified planet.

However, in the battle between communism and capitalism, space technology was also a weapon to demonstrate the superiority of one political system over the other.

The Soviet Union was winning the battle. In 1957, it orbited the first satellite with Sputnik 1. Two years later, the Luna 2 probe was the first human artefact to make contact with the Moon. In February 1961 the Russians launched the Venera 1 probe towards Venus.

As congratulations for Gagarin’s feat poured in from around the world, the vehemently anti-communist Australian prime minister Robert Menzies stayed silent.

His views were echoed by members of the Australian scientific establishment. Sir John Eccles, president of the Australian Academy of Science, said the flight was of little value to humanity. Nuclear scientist Sir Mark Oliphant described it as a stunt.

Physicist Harry Messel said:

Scientifically I am happy, but from the cold-war perspective I am sad … it could very well threaten the freedom of the world if Russia continues to triumph in space.

Sputniks and vodka at the Sydney Trade Fair

The Australian public had other ideas. In August 1961, Sydney hosted an international trade fair with a large Russian pavilion.

Such was the buzz that Henry F. Jensen, the Labor Lord Mayor of Sydney, invited Gagarin to visit as part of his post-flight world tour. A request was sent through the Soviet embassy in Canberra, which passed it on to Moscow. Jensen said:

I am certain Sydney citizens will give him a very warm welcome if he comes here.

Throughout July and August, newspapers reported on whether the invitation had been answered. Anticipation was building.

The Russian pavilion had two life sized replicas of Soviet spacecraft and the public flocked to see them. It was the most popular pavilion at the trade fair (although the mini-bottles of vodka that were given away may have helped too).

Not everyone was happy about it. On August 12, an anonymous caller told police there was a bomb in the Russian pavilion. After evacuation, the bomb threat was proven to be a hoax.

It’s not known if the Lord Mayor’s invitation ever reached Gagarin. Over the next year the cosmonaut visited more than 25 countries on his world tour, but Australia was not among them.

The Space Boomerang

That said, Gagarin still had a close encounter with Australian culture. Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett and his British colleague Anthony Purdy were the first Western journalists invited to interview him privately.

Burchett was the first foreign war correspondent to enter Hiroshima in 1945, and had been hounded out of Australia by the government for his communist sympathies.

Burchett and Purdy met with Gagarin and his interpreters at the State Committee of Foreign Cultural Relations in Moscow, on July 9 1961. They wrote a book about it, contextualising the interview within the broader Soviet space program.

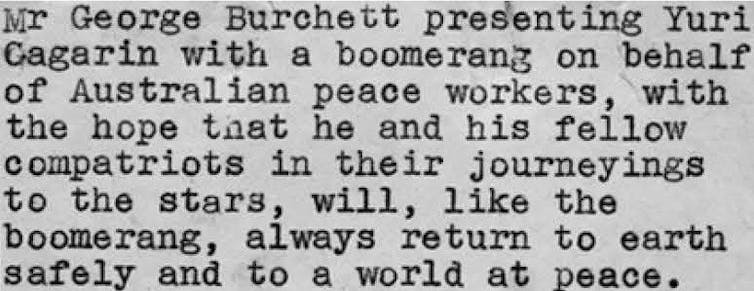

Burchett’s father George was on holidays in Moscow at the time. Just as Gagarin was leaving, George walked in with a boomerang he had in his luggage. He offered it to the cosmonaut, saying “please take this as a symbol of safe return”.

“It always comes back, and I hope you and your colleagues do too.”

Gagarin was delighted, examining the boomerang closely while the interpreters explained its use. They returned his thanks to George Burchett: “I shall treasure it. It’s a nice sort of symbol to have”.

The label on the back of the photograph, now in the National Library of Australia, says:

In January this year, nearly 60 years after Gagarin’s epic flight, a boomerang carved by Kaurna and Narungga man Jack Buckskin was taken onto the International Space Station by astronaut Shannon Walker.

Space politics in the global south

On one hand, Gagarin’s spaceflight was a symbol of unity and peace. On the other, it fostered the fear of Soviet aggression from space that started with Sputnik 1. The US also had to obscure its military objectives in space to create a public perception of peaceful intent.

The world tour was an important exercise in soft diplomacy, particularly when Gagarin visited countries such as Ghana and Brazil, which were not aligned with either the US or USSR.

Soviet technology’s promise of modernisation, as seen at the Sydney Trade Fair, was a powerful lure for nations in Africa, Latin America and Asia.

But many rejected the premise of the Cold War. In May 1961, a newspaper in Uruguay asked readers to imagine

the benefits to be gained if the American and Soviet scientists were to unite their efforts […] if these feats were intended to unite rather than divide.

The paradox is captured in one of the most famous photographs of Yuri Gagarin, where he holds a dove, an international symbol of peace, while wearing his military uniform and decorations.

This image is frequently displayed in the Russian segment of the International Space Station.

Gagarin never flew in space again. He was tragically killed in a jet crash in 1968. Around the world civil, revolutionary and international wars were being waged, the most well-known being the American War (also called the Vietnam War) which continued until 1975.

Perhaps no space traveller has ever returned to a world at peace.

Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ALSO BY ALICE GORMAN IN A SENSE OF PLACE MAGAZINE