By Fergus Ryan, Audrey Fritz and Daria Impiombato

While most major international social media networks remain banned from the Chinese market in the People’s Republic of China, Chinese social media companies are expanding overseas and building up large global audiences. Some of those networks—including WeChat and TikTok—pose challenges, including to freedom of expression, that governments around the world are struggling to deal with.

The Chinese ‘super-app’ WeChat, which is indispensable in China, has approximately 1.2 billion monthly active users worldwide, including 100 million installations outside of China.

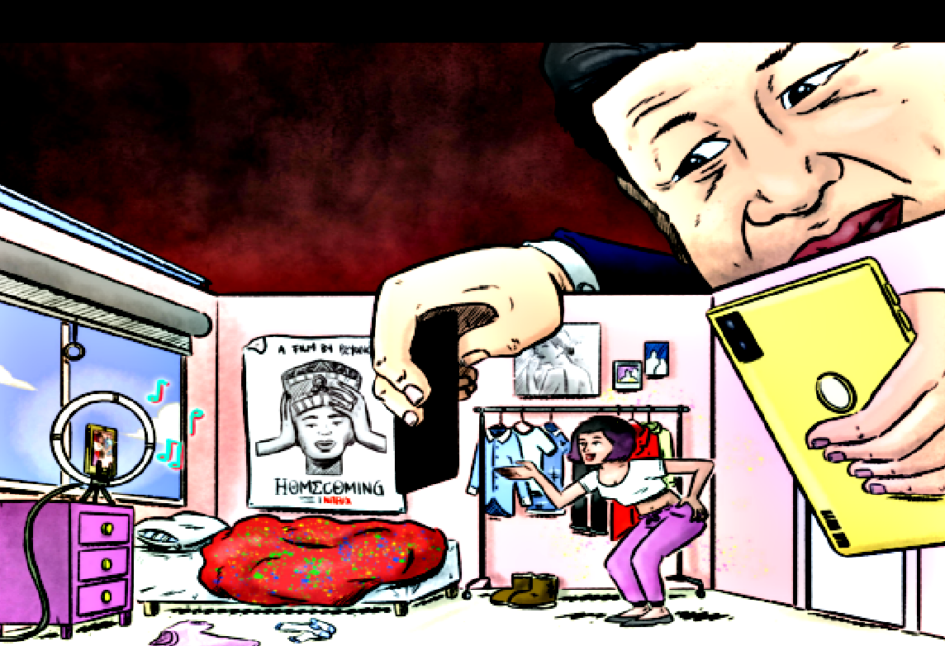

The app has become the long arm of the Chinese regime, extending the PRC’s techno-authoritarian reach into the lives of its citizens and non-citizens in the diaspora. WeChat users outside of China are increasingly finding themselves trapped in a mobile extension of the Great Firewall of China through which they’re subjected to surveillance, censorship and propaganda.

Covid-19 has ushered in an expanded effort to covertly censor and control the public diplomacy communications of foreign governments on WeChat.

Newcomer TikTok, through its unparalleled growth in both Asian and Western markets, has a vastly larger and broader global audience of nearly 700 million as of July 2020.

This report finds that TikTok engages in censorship on a range of political and social topics, while also demoting and suppressing content.

Case studies in this report show how discussions related to LGBTQ+ issues, Xinjiang and protests currently occurring in the US, for example, are being affected by censorship and the curation and control of information. Leaked content moderation documents have previously revealed that TikTok has instructed “its moderators to censor videos that mention Tiananmen Square, Tibetan independence, or the banned religious group Falun Gong,” among other censorship rules.5

Both Tencent and ByteDance, the companies that own and operate WeChat and TikTok, respectively, are subject to China’s security, intelligence, counter-espionage and cybersecurity laws. Internal Chinese Communist Party (CCP) committees at both companies are in place to ensure that the party’s political goals are pursued alongside the companies’ commercial goals. ByteDance CEO Zhang Yiming has stated on the record that he will ensure his products serve to promote the CCP’s propaganda agenda.

While most major international social media platforms have traditionally taken a cautious and public approach to content moderation, TikTok is the first globally popular social media network to take a heavy-handed approach to content moderation. Possessing and deploying the capability to covertly control information flows, across geographical regions, topics and languages, positions TikTok as a powerful political actor with a global reach.

TikTok’s rapid expansion around the world has been punctuated by a string of censorship controversies that it has struggled to explain away.

Initial instances of censorship, were the result of a ‘blunt approach’ to content moderation that TikTok spokespeople admit they deployed in the app’s ‘early days’.

More recent examples of apparent censorship—including posts tagged with #BlackLivesMatter and #GeorgeFloyd—have been explained away by TikTok as the result of a ‘technical glitch’.

Our research suggests that many of these cases were most likely not aberrations, but the side effects of an approach that ByteDance, TikTok’s owner and operator, has used in an attempt to avoid controversy and maintain what it considers to be an apolitical stance as it grows a worldwide audience.

But the very nature of TikTok’s targeted global censorship isn’t apolitical; in fact, it makes the app a politically powerful actor. Our research shows, for example, that hashtags related to LGBTQ+ issues are suppressed on the platform in at least 8 languages. This blunt approach to censorship affects not only citizens of a particular country, but all users speaking those languages, no matter where in the world they live.

TikTok users posting videos with these hashtags are given the impression their posts are just as searchable as posts by other users, but in fact they aren’t. In practice, most of these hashtags are categorised in TikTok’s code10 in the same way that terrorist groups, illicit substances and swear words are treated on the platform.

On some occasions, hashtags are categorised as non-existent, when in fact they’re tagged on videos across the platform. TikTok spokespeople have repeatedly stated that the platform is not ‘influenced by any foreign government, including the Chinese Government’, and that ‘TikTok does not moderate content due to political sensitivities.’

But the censorship techniques outlined below disprove some of those claims and, instead, suggest a preference for protecting and entrenching the sensitivities, and even prejudices, of some governments, including through censoring content that might upset established social views.

On 6 and 7 September ASPI contacted TikTok and provided them with hashtags our research discovered were being shadowbanned and asked for comment on these research findings.

These hashtags were:

• #acab – English, acronym for “all cops are bastards,” use of which began during the George Floyd protests in the United States

• #путинвор – “Putin Is A Thief” in Russian

• #Jokowi – nickname for Joko Widodo, President of Indonesia

• #GayArab – English

• #гей – “Gay” in Russian

• #الجنس_مثلي” – Gay” in Arabic •

#ялесбиянка – “I am a lesbian” in Russian

• #ягей – “I am gay” in Russian

• #gei – “Gay” in Estonian • #gej – “Gay” in Bosnian

• #สมเด็จพระเจา้ลกู เธอเจา้ฟ้าสริวิณั ณวรนี ารรีตันราชกญั ญา – #Princess Sirivannavari Nariratana Rajakanya in Thai

• #กษัตริย์มีไว้ท าไม – “Why Do We Need A King” in Thai

• #ไม่รับปริญญาจากสถาบันกษัตริย์– “I won’t graduate with the monarchy” in Thai

• #جنسي المتحول” – Transgender” in Arabic

• # الجنسي _التحول” – Transgender/transitioning” in Arabic

The response by a TikTok spokesperson was: “As part of our localised approach to moderation, some terms that the ASPI provided were partially restricted due to relevant local laws. Other terms were restricted because they were primarily used when looking for pornographic content, while the Thai phrases the ASPI supplied are either readily found when searched or do not appear to be hashtags that any TikTok users have added to their posts.”

Leaked content moderation guidelines seen by The Guardian in March 2020 barred content related to a specific list of 20 ‘foreign leaders or sensitive figures’ including Kim Jong-il, Kim Il-sung, Mahatma Gandhi, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Kim Jong-un, Shinzo Abe, Park Geun-Hee, Joko Widodo and Narendra Modi.

ByteDance said those rules were retired in May 2019, but our research has found that hashtags related to criticism of the leaders continue to be censored. The censorship ranges from #путинвор (‘Putin Is A Thief’) to even seemingly innocuous hashtags, such as #Jokowi—the politically neutral nickname for Indonesian President Joko Widodo.

These hashtags have been shadow banned by TikTok, meaning that content tagged with them has been suppressed and often totally hidden from public view; posts are made much more difficult to find on the platform though they’re not necessarily deleted.

It’s a more insidious form of censorship in that users are being censored, but often don’t know it because they can still see their own content.

This is an extract from the report TikTok and WeChat: Curating and controlling global information flows from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. This work was funded in part by the US State Department.

The full report can be downloaded from here.