By John Stapleton

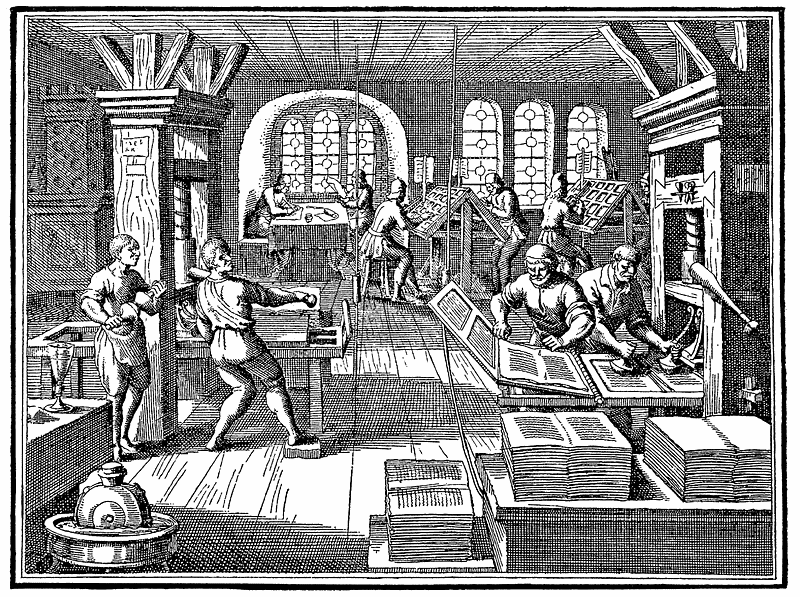

Since the beginning of literature technologies have shaped the written word.

And thereby publishing technologies have shaped history, culture, politics and war.

The adage history is written by the victors has transposed in this truly astonishing era into something else. In fact, in our current time, history is being written by the literate, by those who leave a record.

Across time most lives have gone undocumented, unrecorded, celebrated only in small circles of families and friends, their memory quickly washed away. The lives of farmers and miners and factory workers, soldiers and slaves all vanished with barely a trace.

Even today, despite the billions of words being poured out every day, many stories remain unwritten, and therefore unavailable to future historians — because they do not fall within the concerns of an educated cohort.

That was why books like J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, and in a former time Studs Terkel’s Working, were so striking.

Not because they were beautifully crafted, well written or contained numerous insights into the human condition, the usual leitmotifs of literary appreciation, but for the simple reason that they opened a window onto a world almost entirely undocumented.

History, or the eternal present, the one crowded hour in which we all now live, is written by those with a college degree and something to say.

Or nothing to say at all.

We live in a time when everybody wants to write and nobody wants to read; never mind whether you have anything to say, any talent or genuine vocation.

God Signs

The technologies have made everyone the star of their own show.

Yet we are all but one breath in an infinite future; a single strand in a very much larger story.

Once known as God signs, for they appeared so magical, written words are now everywhere, spurred by mass education and new forms of transmission.

Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, Socrates, not one of them put pen to paper. All of them distrusted the publishing technologies of their time.

Their words spread, their ideas became powerful, because their disciples did not feel the same.

Many of the other prophets, shamans and wise men dotted through history, those exceptional individuals whose disciples did not leave texts to transmit down the generations, remain to us unknown, and thereby unappreciated.

And now we have the internet, and some of the most sophisticated, stylish and easy to use publishing technologies ever created.

Within this transformation comes both liberation, a kind of massive cultural expansion of narrative and freedom of expression, and a motherlode of biases and the herd behavior of an educated, literate class.

Relying purely on clicks as a test of success leads straight to a race to the bottom.

All too often the old sayings are true: education equals indoctrination. Many educated people are incredibly stupid.

As youthful Harvard professor Martin Puchner’s lucid, easily read and most informative of books, The Written World, concludes:

No matter what future historians will find, they will understand better than we do just how transformative our current writing revolution will have been. What we can say for sure is that the world population has grown even as literacy rates have risen sharply, which means that infinitely more writing is being done by more people, and published and read more widely, than ever before. We stand on the verge of a second great explosion — the written world is poised to change yet again.

In The Beginning Was The Word

While old objects and buildings can give us access to the external habits of our ancestors, their stories, fixed and preserved by writing, give us access to their inner lives. The invention of writing divides human evolution into a time that is all but inaccessible to us, and one in which we have access to the minds of others.

Worlds, civilisations, entire traditions have been lost entirely as a result of technologies which did not survive the weathering of time.

The ever expanding amount of content on the internet could easily be lost in a new Dark Age. Many fear that what we are seeing now, liberation and creativity, enslavement to fashionable shibboleths, all the tumult and the shouting of the internet could be shut down. And our present, soon enough to be the past, could vanish as if it never existed.

To illustrate the point:

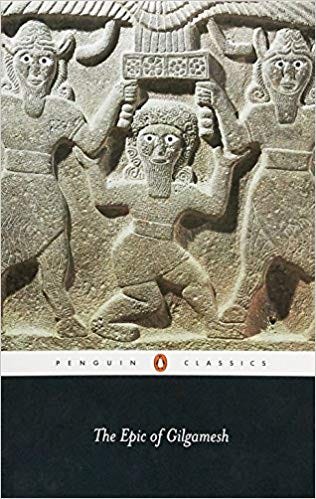

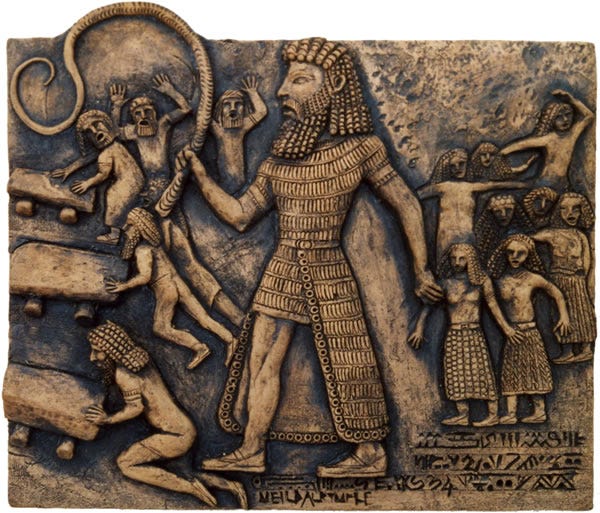

The oldest known example of a substantial literary text, The Epic of Gilgamesh, was lost to history for 2,000 years, buried under the sands of Mesopotamia.

The authors and the scribes of the Assyrian kings who painstakingly wrote on clay tablets clearly thought they were writing for posterity.

But even when it was rediscovered, nobody could read it, for it was written in cuneiform, a writing system designed for making wedge-shaped indentations or incisions into clay or stone. Individual bricks could be inscribed that way, as could bas-reliefs and statues — anything made of clay.

As The Written World records, Austen Henry Layard, an adventurous Englishman who found work with the British ambassador in Constantinople, cut a trench into a mound in Mosul in the 1840s. He hit something, ultimately helping to uncover the ancient city of Nineveh and the first great narrative ever written, The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Mosul is now best known for some of the worst scenes of urban destruction through allied bombs since Dresden, and the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives in a mass slaughter perpetrated by state actors and religious fundamentalists which has been horrifically echoed throughout the Middle East.

But in the 1840s it was the subject of world fascination, a writing obsessed Assyrian city whose libraries nobody could decipher.

Only slowly did Nineveh give up its secrets; including the story of Gilgamesh, a headstrong and unjust king who needed to be taught humility.

What, Martin Pulcher asks, would a world be like without literature, if stories were only told orally and had never been written down. Not just the cosiness of bookstores and libraries would be gone:

Our sense of history, of the rise and fall of empires and nations, would be completely different. Most philosophical and political ideas would never have come into existence, because the literature that gave rise to them wouldn’t have been written. Almost all religious beliefs would disappear along with the scriptures in which they were expressed.

Literature isn’t just for book lovers. Ever since it emerged four thousands years ago, it has shaped the lives of most humans on planet Earth.

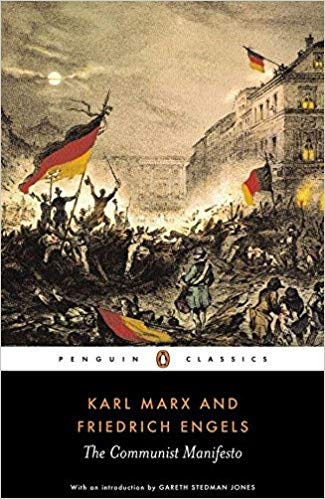

Foundational texts , including the Bible, the Koran and the Communist Manifesto, have accrued power and significance over time until they became source codes for entire cultures, telling people where they came from and how they should live their lives.

Foundational texts were often presided over by priests, who enshrined them at the center of empires and nations.

Kings promoted these texts because they realized that a story could justify conquests and provide cultural cohesion.

The increasing power of foundational texts put literature at the center of many conflicts, including most religious wars.

Writing was invented in Mesopotamia to record economic and political transactions, to centralise power and control the hinterland. It was only over centuries that it evolved into a vehicle for literature.

Humans had been telling stories orally ever since they learned how to communicate with symbolic sounds and use those sounds to tell tales of the past and of the future, of gods and demons, tales that gave communities a shared past and a common destiny. Stories also preserved human experience, telling listeners how to act in difficult situations and how to avoid common pitfalls. Important stories, of the creation of the world or the founding of cities, were sometimes sung by specially appointed bards who had learned these stories by heart and performed them on special occasions. But no one wrote them down.

Game Changer

Now, it seems, everything is written down.

The world of the written word, once restricted to priests and kings, to scribes and powerful elites, has been opened to everybody.

That, in itself, creates other issues.

The educated class, pouring out of colleges and universities, have their own concerns: ambition, progress, success. Regurgitating the theories of their professors.

A technology which places writing in the hands of every even moderately literate person can be the foundation for the greatest burst of creativity in human history, or demonstrate the worst of mob rule.

All the intellectual sleights of hand of the era are in play, the working class male as oppressor, diversity as tyranny.

The peddlers of fake news in the mainstream media condemn the rise of untrammeled, often opinion driven content in the blogosphere. Yet it is their own partisanship which has led to their loss of credibility and the rise of citizen journalists.

At one end of the spectrum, the multiple hurdles that aspiring writers once had to jump through in order to see their work in print have all vanished. All that is needed is the keyboard skills to peck out 220 words and the wherewithal to click on the button Ready to Publish?

Away You Go

Truckloads of juvenalia are dumped onto the internet every single day.

In the past, as the young struggled to find their vocation, many works remained exactly where they most likely should have been: unread and unlamented in a bottom drawer.

Now, everyone’s oft times embarrassing experiments, rather than lying forgotten, are there for all to see.

In the past, those drawn to the romantic notion of being a writer faced a harrowing process, winnowed out by multiple obstacles. Only those with skill, determination, talent and a well developed work ethic made it through.

Many worthy talents died in the struggle, uncelebrated, unrecognised, their specific stories unable to be transmitted to a future audience.

The classic story of the struggling artist remains Vincent van Gogh who, as his letters demonstrate, was as good a writer as he was a painter.

But he sold only one painting in his lifetime, and wrote his volumes of letters to his brother with no hope of publication.

He may have sensed he was writing for history, but the chances were far greater that he would disappear without a trace.

Imagine Vincent in the current era.

He could have his drawings and detailed lyricism blogged by lunchtime and and then be off out to the cafes drinking too much, as was his want.

Would he even be noticed in the flood of a million other voices?

All the more easily to identify you, my dear

As a platform open to everyone, Medium is a vehicle for the superb journalism of The Atlantic just as it is for the latest entry in the “It’s all about me and I feel so bad I haven’t blogged a thousand words today” genre.

American comedian and essayist Dorothy Parker might have got it right when she quipped:

“If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.”

At the other end of spectrum, people like myself, who have worked in newspapers for decades and spent a lifetime pestering editors and chiefs of staff with story ideas, many of which fell on stony ground, Medium is a liberation and a revelation.

Newspapers are insanely frustrating places to work. The corporate culture of media organisations crushes creativity. Far from celebrating ideas, they encourage conformity, herd behavior.

Because your stories don’t fit the corporate agendas or political orientation of the publication, they don’t even get as far as the cutting room floor. They aren’t born at all.

You can spend days trying to convince the Bureau Chief of the value of a particularly good story, only to be ignored or sent off on one idiot assignment or another.

There’s an old saying about journalism:

A young man’s sandpit, an old man’s quicksand.

In my final years as a staff reporter I became all too familiar with that stare from the Chief of Staff: “Just shut up and do it. The last thing we need around here is an artiste.”

In the end I gave up. I couldn’t leave because I had young children to take care of, but inside, I had given up.

In a world of top-down journalism, where stories all originate with government reports or from the mouths of politicians, there is no room to look at the way life is actually lived, out there in the factories and workshops of deep-heart suburbia. Whole swathes of experience just never make it onto the printed page.

But then along comes Medium, which offers everyone the opportunity to do their very best.

That, in itself, is a remarkable thing. Where it all ends those of us alive today will never know.

As the recent books Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow and Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence have both posited, humans are about to take the next great step in the evolution of the species.

Science fiction becomes fact every day of the week.

If a powerful AI was searching for the greatest intellects and shining talents of a generation for upload to a kind of expanding collective intelligence, it would invent a platform exactly like Medium — where emerging writers can chance their game next to those already established in their fields.

We think we’re so damn smart.

We don’t know the half of it.

And we have no idea what the future holds.

One Thing Remains True: The Power of Stories

The Written World:

The impulse to tell stories, to put events into a sequence, to form plots and bring them to a conclusion, is so fundamental that it is as if this impulse is biologically rooted in our species. We are driven to make connections, from A to B and from B to C. In the process, we develop ideas of how to get from one point to the next, what drives a story forward, whether the answer is cosmic fate, chair, social forces comma or the will of a protagonist.

Often characters harbour a secret they must not reveal, and yet we long to pry into it, and by the law of storytelling, their secret is forced out of them, if only to satisfy the king’s and our curiosity. No matter what forces drive these protagonists, we watched them make their way through hostile or friendly circumstances, and before we know it, a storyteller has created an entire world.

The worlds of our stories often obey different rules, some fantastic, some sober, set in the remote past or remote parts of the world, others more familiar and closer to home. This is what imagination and language allow us to do, to create scenes that are different from what we see right in front of our eyes, to make up a world with words. In this storytelling universe, anyone you meet on the street harbours a story, often full of marvels and coincidences; a beggar might have been born a king, and even a simple porter may have something to tell.

Everyone is a story.

John Stapleton is the editor of A Sense of Place Magazine. He worked as a journalist on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.

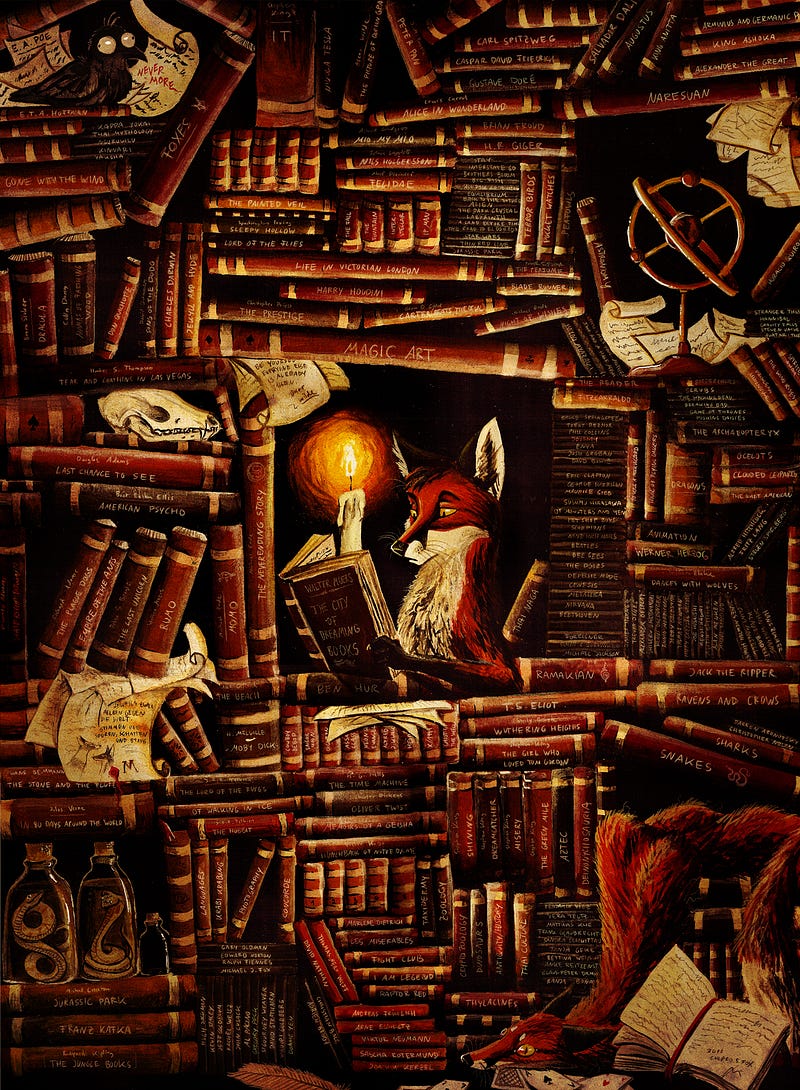

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS