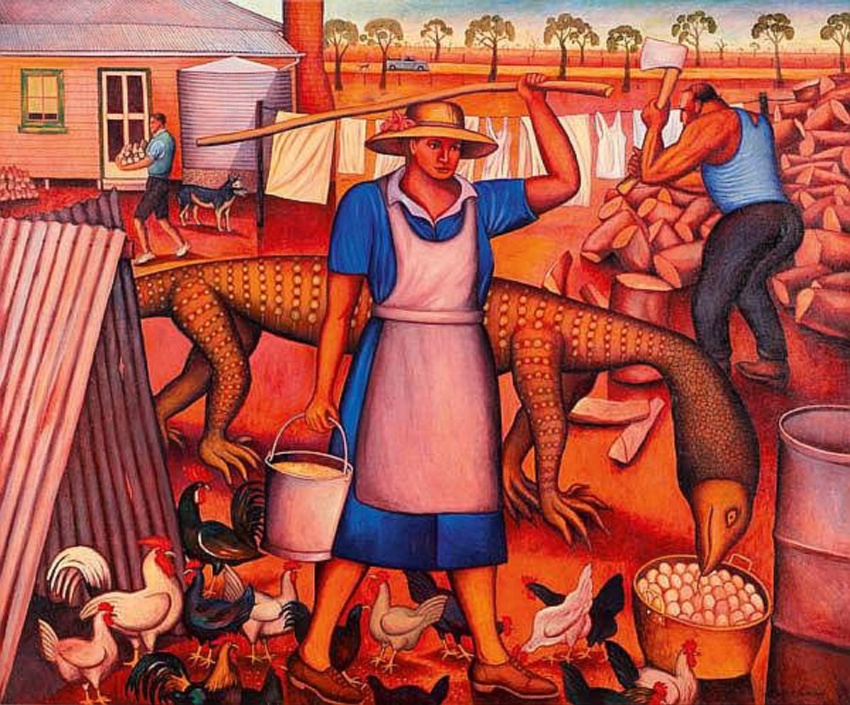

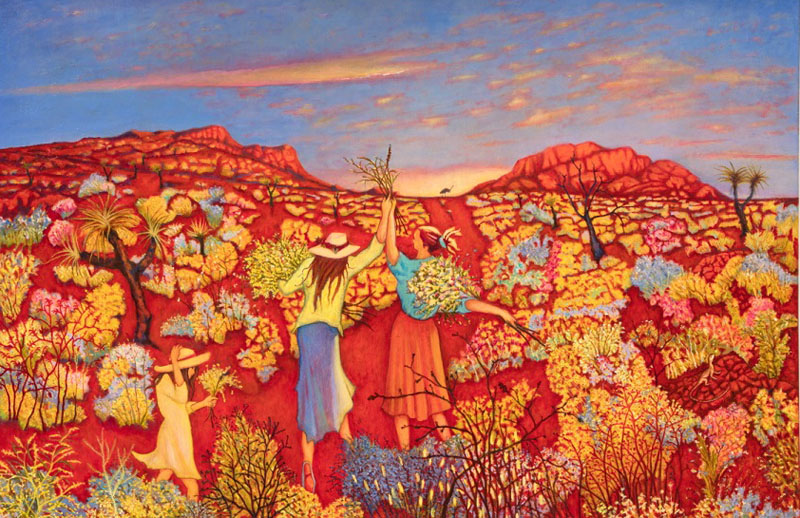

By Fred Pawle: Spiked. Artwork by Bob Marchant.

This once happy and freedom-loving nation is being crushed by its pro-lockdown elites.

People who once thought they’d won the lottery of life by being born in Australia now wake in fright every day to the sudden realisation that they are living in a 21st-century penal colony. The country they once loved has been replaced by something they barely recognise.

The restrictions imposed in response to the pandemic are just the start of it. People have been confined to their houses, prevented from going to school or work, denied the freedom to cross state borders even to see a dying relative, and coerced to take a vaccine in order hopefully to regain the freedoms that were once their birthright.

Worse, these restrictions are being imposed by authoritarians who have seemingly come from nowhere and now dominate all of Australia’s positions of power, from the government to big business. These people are unlike any ruling elite Australia has ever known.

There were, to be sure, harsh authoritarians in middle levels of power during the nation’s initial 19th-century incarnation as a penal colony, especially at Port Arthur and Norfolk Island. But they never actually ran Australia.

From the moment Arthur Phillip hoisted the Union flag at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788, Australia has pursued, with a level of success almost unparalleled anywhere in history, the ideas that all people are equal and that freedom begets prosperity.

These founding principles were a combination of the European Enlightenment as well as necessity. Whatever class divide was felt by the marines and convicts as they boarded the 11 ships of the First Fleet, which Phillip commanded, was greatly diminished by the close confines they endured during the six-month journey and the inhospitably harsh continent on to which they disembarked together at the end of it.

Francis Grose, who replaced Phillip as colonial governor in 1792, kickstarted the Australian economy by granting land to soldiers and freed convicts, encouraging them to fend for themselves without government interference.

There wasn’t time to sit around pondering the risks, benefits and limitations of freedom, let alone the virtues of men. It was a matter of survival in a land of harsh extremes, and the only way to do so was to encourage independence, from which a sense of rugged individualism evolved and a culture of unspoken optimism and egalitarianism was born.

Since then, Australians have, like the original settlers, never felt the need to explain the ideas on which their nation was founded. They have simply believed their version of Enlightenment truths to be self-evident in the standard of living they enjoyed and the audacious disrespect they showed for other, older cultures.

I grew up in a country where such confidence was ubiquitous. A lack of academic achievement was never an impediment as long as you worked hard. Obstacles that were insurmountable to people from other countries were mere challenges to us. And we approached it all with a fatalistic humour that seemed all our own.

When Alan Bond, a former signwriter who became a very wealthy property developer, won the America’s Cup yacht race in 1983, the then prime minister, Bob Hawke, said, ‘Any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up today is a bum’.

Hawke wasn’t encouraging the nation to chuck a collective sickie. He was simply revelling in the rewards of Bond’s hard work. We all laughed at Hawke’s irreverent enthusiasm and went to work anyway, knowing how lucky we were to live in a nation where such opportunities abounded. They were unbelievably happy times.

Now, we are being ordered by the government not only to stay away from work, but also to stay away from each other.

New South Wales chief health officer Kerry Chant became world famous recently when a video of her went viral. In it, she said, in the patronising tone of a school matron:

‘It is human nature to engage in conversation with others, to be friendly. Unfortunately, this is not the time to do that. So even if you run into your nextdoor neighbour, in the shopping centre, at Coles, Woolworths or Aldi or any other grocery shop, don’t start up a conversation.’

kerry chant

Some of us thought: who the bloody hell is this sheila? Not only had I never heard of her, I hadn’t listened to anything anyone like her had said since I’d been kicked out of high school. My robust upbringing among ratbags and larrikins in the Australian suburbs had instilled in me an instinctive and entirely rational distrust of anyone who, like her, placed an undue significance on obedience above personal freedom and responsibility. My life has been, and continues to be, all the better for it.

New South Wales residents were surprised to learn they had been paying Chant’s wages since she joined the public service in 1991. Like many of her fellow neo-authoritarians, she had spent her entire career cloistered away from the freely enterprising general population, biding her time until the opportunity arose to exercise the powers none of us knew she had.

Now she and her type are all around us, telling us what to do every minute of the day. She is emblematic of Australia’s new elite, from the cops who told me to ‘move on’ when I was enjoying the sunshine by myself at Bondi Beach recently, to prime minister Scott Morrison, who peppers his updates on the latest panicking policies with reminders that ‘we are all in this together’.

No, we’re not. The elite in government and the bureaucracy, some of whom have even been granted pay rises since these lockdowns began, are laughing all the way to the bank while the nation’s middle-class, small-business entrepreneurs – the cultural descendants of the emancipated landowners of the 19th century – are driven to despair and bankruptcy. These elitists might evoke the Australian traditions of ‘mateship’ and the ‘fair go’, but they advocate nothing of the kind. Instead, they impose rules that are only possible under their newly created ’emergency powers’, and which would have been comprehensively ridiculed and rejected in any state or federal parliament at any other time in our history.

Sadly, there are few signs of dissent, let alone rebellion, among the populace. Polling companies are finding that modern Australians approve of being locked down by the government and even admire the grim, tough-talking leaders who impose these restrictions on them.

The mystery is, how did we get here? What happened to the culture that built this thriving nation on a harsh continent from scratch, that encouraged young men to fight so gallantly in other people’s wars, and that cherished freedom with such unbridled vigour? In short, and in the traditional vernacular, how did Australians go from being deadset champions to a nation of piss-weak wimps?

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly where it went wrong. I grew up among surfers, and can testify that in my lifetime the surfing subculture has been completely consumed by the woke mainstream. What was once a culture for dangerously drug-abusing, sexually promiscuous, nomadic adventurers is now a hobby pursued by dreary environmentalists and conformists. It’s also an Olympic sport.

Our football codes have made a similar transition. The Australian Rules footy I grew up watching was essentially controlled violence, a cathartic outlet for players and fans alike, a weekly escape from the more polite conventions of a safe society. These days, footy is just another vehicle for woke causes, and the action has been reduced from a viscerally brutal theatre for working-class blokes to a safe demonstration of athleticism and skill.

These are microcosms of the wider culture. Where once we were independent and resilient, we are now a nation that looks to its government for moral guidance and economic protection.

My late friend Bill Leak was Australia’s greatest ever cartoonist. He died in 2017 after being hounded by woke mobs and the Australian Human Rights Commission for drawing cartoons that were deliberately misread as racist. Although he was a smoker and had been a heavy drinker, I believe the anguish the mobs and the AHRC caused him contributed to the heart condition that killed him.

My biography of him, Die Laughing, will soon be published. I wrote it not only as a tribute to a life well lived, but also as a reminder of an Australia that is rapidly disappearing.

Bill spent his early twenties pursuing a career as an artist in Britain and Europe, visiting all the great galleries and observing the pros and cons of cultures much older than his own. While he was impressed with Europe’s enormous artistic heritage, he also saw it as a burden. ‘The glorious traditions of European culture don’t only enrich the lives of the people, they also weigh them down’, he wrote to his sister Lynne from London in 1978. ‘I think one of the great strengths of Australia’, he continued, ‘is expressed in the way people say, “Oh, bullshit!” to everything. As long as people keep recognising and condemning bullshit over there, everything will be all right, I think.’

Bill lived his entire life by this imperative – he was simply incapable of not calling ‘bullshit’ whenever he saw it. Ordinary Australians loved him for it, regardless of the criticism he provoked from censorious, humourless scolds. He was the epitome of all that was wonderful about this naturally optimistic, unabashed, funny and happy country.

He would weep with despair at what it’s becoming.

Fred Pawle is one of Austalia’s most experienced journalists and the author of Die Laughing: The Biography of Bill Leak, which is available at Dielaughing.org.au.

Bob Marchant was born and raised in the Wimmera district of country Victoria. His experiences during these early, formative years in the Australian outback are often depicted in his paintings. Bob studied at the Royal Melbourne Technical Collage (now known as RMIT), however he only began painting full-time at the age of forty when he returned to Australia after living in London for almost twenty years. Bob burst onto the Australian art scene, winning two consecutive Sulman Prizes in 1988 and 1989, and the Mosman Art Prize in 1992. Bob has had solo exhibitions in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, France and the USA, and his work is represented in both private and public collections, nationally and internationally.

This piece was originally published in Spiked.

It has been republished in A Sense of Place Magazine with their kind permission.

September 14, 2021 at 7:48 pm

Awkwardly apt. Accurate too ✅