By Melissa Sweet, Editor of Croakey

Immense disruption to societies, and people’s lives and work will be necessary over many months if there is to be any hope of preventing large numbers of deaths from COVID-19.

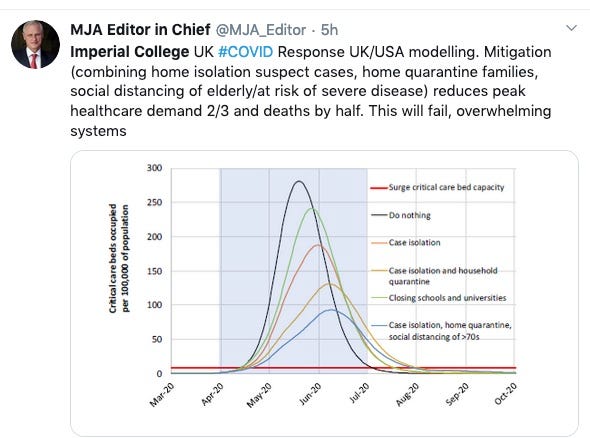

That is the suggestion from modelling by researchers at Imperial College in London whose report, published on 16 March, examined a range of scenarios for Great Britain and the United States. They said their findings “are equally applicable to most high-income countries”.

They explored the potential impact of two approaches:

(a) mitigation, which focuses on slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread — reducing peak healthcare demand while protecting those most at risk of severe disease from infection, and

(b) suppression, which aims to reverse epidemic growth, reducing case numbers to low levels and maintaining that situation indefinitely.

The researchers concluded that suppression is “the only viable strategy at the current time”, but warned that “the social and economic effects of the measures which are needed to achieve this policy goal will be profound”.

They also stressed that it is not certain suppression will succeed long-term, and said that “no public health intervention with such disruptive effects on society has been previously attempted for such a long duration of time. How populations and societies will respond remains unclear.”

The researchers said each approach had major challenges.

They found that that optimal mitigation policies (combining home isolation of suspect cases, home quarantine of those living in the same household as suspect cases, and social distancing of the elderly and others at most risk of severe disease) might reduce peak healthcare demand by two-thirds, and deaths by half.

However, the resulting mitigated epidemic would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (especially intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over.

Preferred option

For countries able to achieve it, this left suppression as the preferred policy option:

We show that in the UK and US context, suppression will minimally require a combination of social distancing of the entire population, home isolation of cases and household quarantine of their family members.

This may need to be supplemented by school and university closures, though it should be recognised that such closures may have negative impacts on health systems due to increased absenteeism.

The major challenge of suppression is that this type of intensive intervention package — or something equivalently effective at reducing transmission — will need to be maintained until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more) — given that we predict that transmission will quickly rebound if interventions are relaxed.”

The researchers also cautioned that while the experience in China and South Korea showed that suppression is possible in the short term, it remained to be seen whether it was possible long-term.

For epidemic mitigation, the combination of case isolation, household quarantine and social distancing of those at higher risk of severe outcomes (older people and those with other underlying health conditions) were the most effective policy combination.

However, even in the best-case mitigation scenario, the surge limits for both general ward and intensive care unit beds would be exceeded by at least eight-fold. Even if all patients were able to be treated under this approach, the researchers predicted there would still be in the order of 250,000 deaths in Great Britain, and 1.1–1.2 million deaths in the US.

Policy switches

The Guardian reports these new modelling estimates are why the UK Government has switched its policy away from mitigation to suppression, including a shift to population-wide social distancing, in the hope of greatly reducing the number of anticipated deaths.

The modelling is also understood to have informed new White House guidelines urging Americans to avoid gatherings of more than 10 people, according to The New York Times.

Testing times

Meanwhile, as the Australian Government comes under pressure to step up its testing regime, the World Health Organization has urged countries to do much more around testing, isolation and contact tracing.

Describing the pandemic as “the defining global health crisis of our time,” Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said:

You cannot fight a fire blindfolded. And we cannot stop this pandemic if we don’t know who is infected.

We have a simple message for all countries: test, test, test.

Test every suspected case.

If they test positive, isolate them and find out who they have been in close contact with up to two days before they developed symptoms, and test those people too. [NOTE: WHO recommends testing contacts of confirmed cases only if they show symptoms of COVID-19].”

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) today released a communiqué calling for better communications to the public and for a greater effort to slow the pace of the outbreak’s spread:

Consistent, succinct and contemporaneous communication across all media from a single trusted source must be provided.

The public has been receiving conflicting and inaccurate information about when they need to be tested, and how they should approach testing, and what comprises effective prevention and mitigation strategies.

The messaging has been improving, but this confusion is causing undue community distress and system inefficiency.”

The AMA also said Australia must act to prevent community transmission by effectively implementing the announced ban on mass public gatherings; encouraging social distancing; and, minimising social contact where alternatives are readily available (such as working from home, virtual meetings).

Public education on effective and sensitive public distancing measures should focus on individual as well as institutional responsibilities, and planning should be undertaken for potential advanced education centre closures, workplace restrictions, and the possibility of school closures.

Focus on social determinants

Community groups are also calling for action on the social determinants of health at play with the pandemic.

The national peak body for homelessness has urged the Federal Government to immediately deliver emergency payments to cover the rent for casual and contract workers who lose their income during the pandemic to prevent a “tsunami of homelessness”.

“Tens of thousands of Australian households have lost the wages they need to pay their rent because of the mass cancellation of events, and requirement on growing numbers of people to self-isolate or quarantine,” says Jenny Smith, Chair, Homelessness Australia.

“To avoid this crisis of lost wages quickly translating into a tsunami of homelessness, the Federal Government must immediately provide people with emergency payments, so they can keep a roof over their head and food on the table.”

A pre-print article in the Medical Journal of Australia has also highlighted the challenges for homeless people at this time:

Implementation of advice to the public and general practitioners on minimising risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission is immensely difficult for people experiencing homelessness and the health services working with them. Yet this is a population group more vulnerable to infection than most.

… as new precautionary measures are being announced daily, it is critical that further marginalisation for this group is not an unintended consequence.”

The Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) has written to the Prime Minister with 31 calls for action, including asking the Government to urgently convene a community sector round-table in partnership with ACOSS to engage with peaks and large service providers about the impacts of COVID-19 on the community, and communication needs, particularly for people on low incomes and with vulnerability.

ACOSS also called on the Government to ensure that Personal Protective Equipment is available for support workers who provide support in the home, both NDIS workers and Homecare workers.

Meanwhile, the Alliance for Gambling Reform has issued a statement supporting calls from leading public health and addictive behaviour researchers to temporarily shut down poker machines during the pandemic.

Alliance Chief Advocate, the Rev Tim Costello, said a temporary shutdown of all electronic gaming machines, along with casinos, was a sensible public health measure to prevent further spread of the virus, and to prevent gambling venues from profiting from people experiencing high levels of stress.

“Poker machines by their very nature involve the repeated touching of buttons and screens on surfaces that are known to retain the virus for some time,” he said.

This story was originally published in leading Australian health policy journal Croakey.

Melissa Sweet is one of the nation’s most experienced health reporters, with a long and distinguished career in newspapers before going on to found and edit her own journal Croakey.