It’s not every day you get to interview one of the world’s most famous authors, someone who created an expression which entered the English language.

Catch 22.

The Oxford dictionary defines a Catch 22 as:

A dilemma or difficult circumstance from which there is no escape because of mutually conflicting or dependent conditions.

as modifier ‘a catch-22 situation’

Origin

1970s: title of a novel by Joseph Heller (1961), in which the main character feigns madness in order to avoid dangerous combat missions, but his desire to avoid them is taken to prove his sanity.

Personally, having a whimsical dose of dyslexia, I could never get my head around all the conundrums, contradictions and double traps of Catch 22.

Retired American journalist James Donahue puts it more simply than I ever could when he writes that the term Catch-22 was defined by the fictional character Doc Daneeka, an army psychiatrist who understood the paradox.

“The term for the paradox and the book title was randomly chosen by author Heller and has since become commonly used.

“That is because the dilemmas described in his book are among the most common paradoxes most people, especially military and government service personnel, are forced to deal with.”

The term Catch-22 refers to the various absurd bureaucratic constraints placed on military personnel that cannot be resolved without breaking the rules.

The pivotal Catch-22 is a bomber pilot who attempts to prove his own insanity in order to escape increasingly dangerous missions. But this very attempt to stay alive proves his sanity.

But there are many others.

The novel contains numerous examples of Catch-22s.

There was the case of the prostitute that refused to accept a marriage proposal from one of the soldiers. She explained that he had to be crazy to want to marry a non-virgin and she would never marry a crazy man. By her logic then, all men that refuse to marry her are sane and those that wish to marry her are crazy. Thus she will never be married because she is not a virgin. The woman is clearly caught in a Catch-22 of her own making.

He’s From One of Our Ghastly Colonies Darling

Many authors feign a certain reluctance to flog their wares, as if as artistes their creative purity should not be sullied by grubby commerciality.

But when there’s a new book out, that is product to sell, all the living legends do the centres of the English speaking world, New York and London — where I was living in the 1980s.

These same legends rarely, of course, made it as far as Sydney, where I was from.

Despite having crossed the first bridge and joined the queue of journalists lining up to interview whichever celebrity was in London that week, there were other obstacles to overcome.

Being from some notoriously remote, uncultured, illiterate colony like Australia, God forbid, was one of those.

The English were born snobs.

But if you were selling a new book and your writer was in contracted interview mode, a public relations person was happy enough to slot in an aspirant from bumfucknowheresville.

The more crowded their schedule, the better the PR person looked.

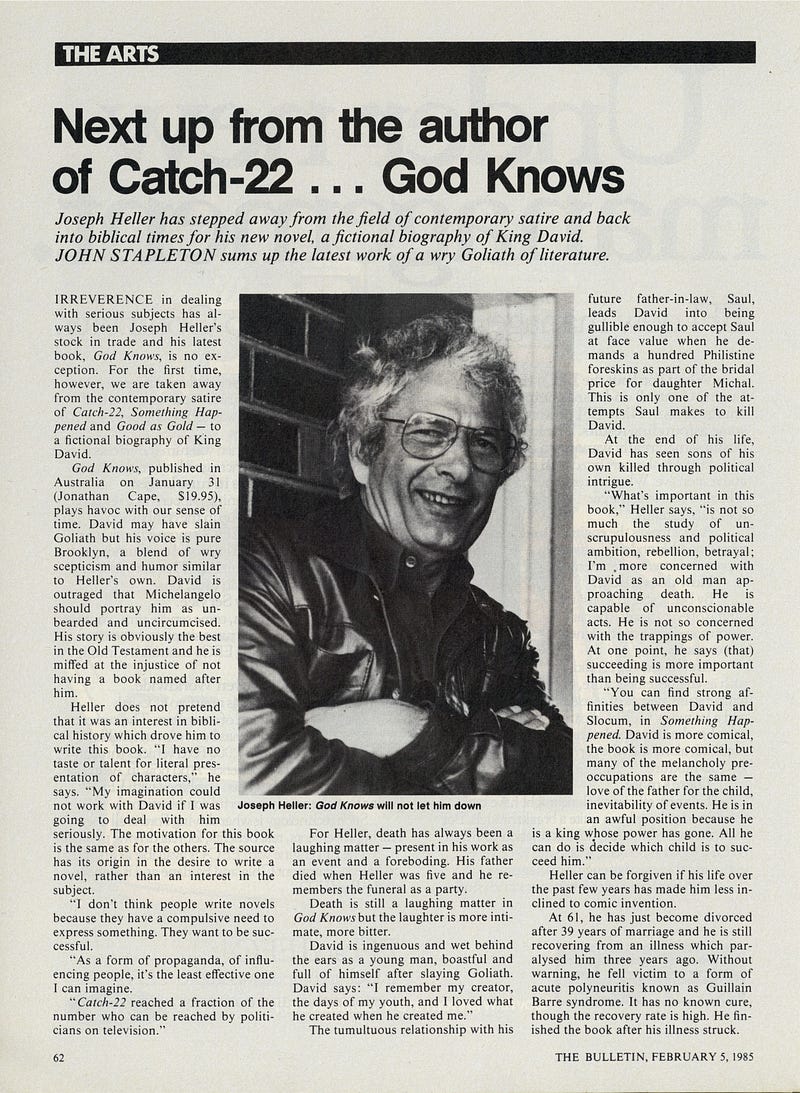

Would you like an interview with Joseph Heller, author of Catch-22, about his latest book God Knows, went down a treat with the now defunct then historic news magazine The Bulletin.

Back in the early part of the 20th century The Bulletin had pioneered and championed Australian authors, including bush balladeers such as Banjo Patterson and that most poignant of Australia’s poet-alcoholics, Henry Lawson:

For the Southern Land is the Poet’s Home, and over the world’s wide roam,

There was never till now a binjied bard that lived in a poet’s home, old man;

For the poet’s home was a hell on earth, and I want you to understand,

That it isn’t exactly a paradise down here in the Southern Land,

Old chap,

Down here in the Southern Land.

For Money and For Love

Living in London in the 1980s and pursuing famous authors, as the months passed it became obvious why I was being slotted in at 9 am to interview people like Anthony Burgess.

I was low down the pecking order.

In crowded days of radio, television, newspaper and magazine interviews, of being feted at book signings and literary luncheons, the morning slots were the least prestigious.

As I was doing many of the interviews for the Friday review section of Australia’s well regarded Financial Review, at the time known for its rigorous journalism, I soon worked out the trick words to get the public relations person onside.

My standard line was: “It’s for The Financial Review, the Australian equivalent of The Financial Times.”

The Financial Times, then published distinctively on pale pink newsprint, was one of England’s most prestigious newspapers and an organ any PR hack would like their subject to be showcased in.

Unlike the left wing Guardian at least the readership of stockbrokers, investors and companydirectors had enough money to buy whatever was being promoted.

I sometimes heard the almost invariably young female public relations person who was shepherding around the author repeating my phraseology word for word as she explained to the interview subject who I was.

In those days, going through another phase of drinking and partying in the London clubs, I wasn’t always at my best at 9 am. But then neither were the authors.

So when it came to Joseph Heller I reacted with mock horror when the public relations woman tried to slot me in at the allotted hour.

“Who wants to be interviewed at 9 am in the morning?” I demanded to know. “Not me. Don’t be ridiculous.”

“But he’s got interviews scheduled for every hour of the day,” the PR woman protested. “There’s nothing I can do.”

I held my ground.

And thus it was that I came to have lunch in London’s famous Covent Garden with Joseph Heller, the author of Catch 22, one of the most famous novels of the 20th Century.

Something Happened

Well actually, not a lot happened.

Joseph Heller never repeated the success of Catch 22, the war book which inspired movies, theatrical productions and whose name adorned everything from garages to bars.

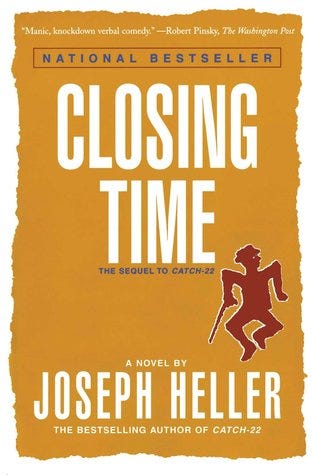

In fact many of Heller’s books were excruciatingly long and rather dull.

Well I found them so, as I waded through volume after volume in preparation for the interview.

I arrived at the trendy little French restaurant near Covent Garden nominated by the public relations woman ahead of time and sat a little uncomfortably amongst the starched white linen tablecloths, the restaurant yet to fill with the lunchtime crowd. The crowd I hung with at the time was a tad more bohemian.

I was uncharacteristically nervous. I had come to expect that life would plunge from one fascinating, exhilarating, wildly exuberant moment to the next. Interviewing one of the world’s most famous authors was just another incident in an already very crowded life.

Or so I told myself.

Nothing to be afraid of.

Finally, a little later than the appointed hour, the PR woman with Joseph Heller in tow arrived, and I rose from the table to greet them.

They were full of the news that they had just passed an employment agency called Catch-22.

Which of course provoked the obvious question: what it was like to have written a novel whose title had literally entered the English language.

The PR woman didn’t get much of a look in after that; as the conversation sailed across seemingly everything and the hour and a bit disappeared as rapidly as the meal in front of us.

Perhaps he was more reflective than he might otherwise have been: he had just broken up from a 39-year marriage and survived a life threatening illness.

Some of his later books, such as Something Happened, have essentially disappeared from public view and might have been a tad on the long side, but in person Heller was charm personified.

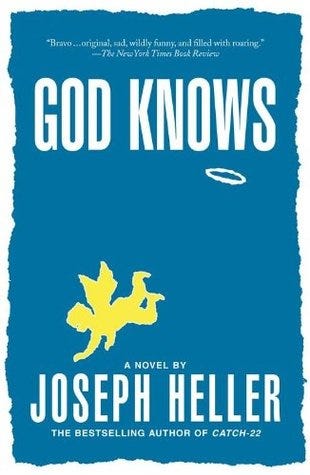

God Knows

We talked about everything, even the product being flogged at the time, God Knows, a fictional biography of King David which plays havoc with time.

David may have slain Goliath but his voice was pure Brooklyn, a blend of wry scepticism and humour similar to Heller’s own.

Heller does not pretend that it was an interest in Biblical history which drove him to write this book.

I have no taste or talent for literal presentation of characters. My imagination could not work with David if I was going to deal with him seriously. The motivation for this book is the same as for the others. The source has its origin in the desire to write a novel, rather than an interest in the subject.

I don’t think people write novels because they have a compulsive need to express something. They want to be successful.

As a form of propaganda, of influencing people, it’s the least effective one I can imagine.

Catch-22 reached a fraction of the number who can be reached by politicians on television.

Denouement

Joseph Heller was 61 when I interviewed him and found him so very personable indeed. He died in 1999 at the age of 76.

In 2011 the 50th anniversary of the publication of Catch-22 was widely remarked.

Speaking to the BBC to mark the occasion, Paul Bates, 42, a lieutenant colonel with the British army’s Royal Artillery regiment deployed to Afghanistan, said Heller was spot on in his descriptions of military life.

Many observers say that the character of conflict changes because of such things as technological advances. But the nature of conflict, the brutal, chaotic nature of it and the associated emotions — fear, exhilaration, anxiety, courage — remain the same.

I see that in the book and have experienced it throughout my time in the Army. I myself am a fatalist. If it’s your time, it’s your time.

Adapted for A Sense of Place Magazine from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as a journalist on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOK: