By Paul Gregoire. Sydney Criminal Lawyers Blog.

The judge presiding over Julian Assange’s extradition case, Judge Vanessa Baraitser, indicated last week that she wouldn’t be making a decision on whether the Australian journalist and publisher will be sent to the United States, until after the November election.

Currently, the fourth week of extradition hearings are underway, which marks the close of evidence.

Having been held on remand in the UK on behalf of the US since last September, if the Wikileaks founder is extradited, he will face 18 espionage charges with a combined maximum of 175 years.

And if our fellow Australian citizen is sent to the US and found guilty on the Trumped up charges, he’s to be held under a correctional regime known as special administrative measures, which entails being imprisoned in a supermax facility and denied contact with the outside world.

Meanwhile, the Morrison government is simply looking the other way. This is in marked contrast to the approach the Coalition took in helping journalists Peter Greste in Egypt and James Ricketson in Cambodia, as well as how it’s currently assisting news anchor Cheng Lei incarcerated in China.

A list as long as the injustice

As the extradition trial moved into its third week, 167 politicians from 27 nations around the globe endorsed an open letter, calling out the UK government for acting in violation of both domestic and international laws in relation to its part in the extradition case.

Lawyers for Assange released the letter in mid-August, when it was initially signed by 189 independent international lawyers, judges, legal academics and lawyers’ associations, as they collectively condemned the Kafkaesque nature of the trial and the ongoing torture of Assange.

The politicians endorsing the letter include 13 current and former heads of state. And on the Australian side, the list includes Independent federal MP Andrew Wilkie, Australian Greens leader Adam Bandt and Senator Nick McKim.

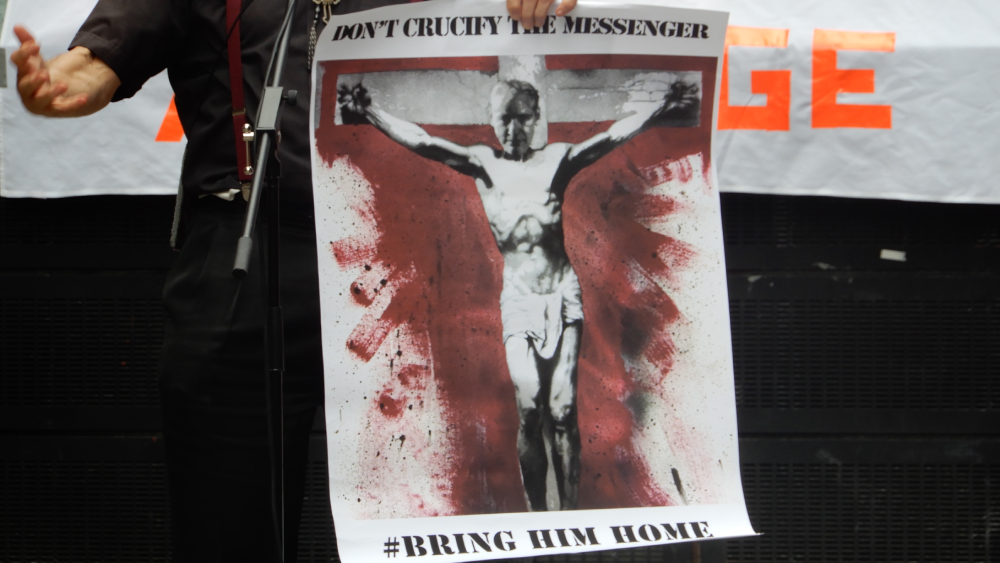

Co-chair of the Bring Julian Assange Home Parliamentary Group Wilkie has made clear that the fact that Julian is being “politically persecuted” for exposing the war crimes of the US, which is now seeking to extradite him, is “unjust in the extreme and arguably illegal under British law”.

Truth-telling

Independent Member for Clark Andrew Wilkie flew to London last February to visit Assange in Belmarsh Prison.

Following the visit, the MP remarked, “at the end of the day, no one should be punished for doing the right thing”.

And Wilkie should know. Back in 2003, he resigned his position as a senior intelligence officer at the now defunct Office of National Assessments, so he could speak out against the false pretences the Howard government was employing to justify entering into war with Iraq.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Mr Wilkie about the treatment Julian has had to bear during his time in Belmarsh Prison, why the prime minister is shirking his responsibilities on this matter, and how Morrison could quite probably save Assange from the injustices he’s now facing.

Firstly, Judge Baraitser has indicated that an extradition decision on Assange won’t be made until after the 3 November US election. Mr Wilkie, could this be his saving grace?

It’s a very curious decision by the judge to delay it until after the election result. That would seem to be at odds with my understanding of the law: that it should run its course regardless of politics.

The fact that the judge has made that decision highlights how intensely political this whole matter is: that it’s not about justice being served, it’s about politicians wanting a political outcome.

Having said all that, maybe after the election whoever is the president will be more favourably disposed to Assange and have the good sense to drop the whole matter.

One of the extraordinary aspects to the Assange case is that the United States has been able to reach out across international borders and arrest him for alleged espionage crimes committed on the soil of other nations.

In your opinion, what are the implications of this unprecedented move by the US government?

A lot of people are very concerned about this claim to extraterritoriality. That’s basically what’s going on here. The US is claiming that it has jurisdiction globally, which, of course, it doesn’t.

This is a remarkable turn of events, and it will be a chilling precedent if Assange is extradited.

It should put all Australians on notice that if any of us offend a foreign government in any way that our government is open to a foreign government getting their hands on us.

It should be especially chilling for journalists. If this precedent is set, does that mean if an Australian journalist writing in Australia offends the Saudi or the Chinese or the Russian regime, and the government wants to maintain good relations with that country, that it hands over our citizens?

Well, of course, it shouldn’t, but this Assange matter really does risk establishing that precedent.

Last week, you joined 166 other prominent politicians from around the globe in signing an open letter condemning the illegality of the extradition proceedings and calling for the immediate release of Assange.

In your opinion, how do the extradition hearings and the continued detainment of Julian contravene domestic and international law?

Talking about the technical aspects, the extradition agreement between the UK and the US specifically rules out extradition on political grounds, and this is an intensely political matter.

So, this should have been thrown out of court on the first day, because the US is attempting to extradite someone on political grounds, and the treaty simply doesn’t allow that.

From a technical point of view, I see no basis for the extradition.

From a philosophical point of view, Julian Assange and Wikileaks are basically journalists and publishers publishing information in the public interest. This is a terrible attack on the free press.

The hypocrisy is writ large by the US, because freedom of the media is guaranteed in their constitution.

So, they’re saying that the constitution of the US doesn’t apply to Julian Assange and Wikileaks. But, at the same time, they’re claiming extraterritoriality over him.

This whole matter is riddled with inconsistency and hypocrisy.

In February this year, you took yourself to London to visit Julian in Belmarsh Prison. What did you see? And how was he holding up?

He was putting on a brave face. But he’s clearly in a very fragile state. He is clearly a broken man.

The UK authorities say he hasn’t been in solitary confinement, but that is nonsense. He’s been confined to his cell for almost every hour of every day for over 18 months now. And before that, he was almost in solitary confinement in the Ecuadorian embassy for many years.

By any reasonable definition that’s psychological torture – the 18 months in Belmarsh in virtual solitary. So, it’s entirely understandable that he is broken, fragile and vulnerable.

He’s not in the best of health. He has a history of respiratory ailments. And I would have said that Belmarsh is the last place someone like that should be now.

George Christensen and I have made the case to the British government that, if nothing else, allow him to go into the community.

He is not a hardened criminal. He hasn’t been convicted of anything. He hasn’t been charged with anything in the UK. He’s not a flight risk, because his family is in the UK.

He should be in the community. Put a bracelet on him, or whatever is required. But he should not be in Belmarsh.

The Morrison government has done next to nothing to help an Australian journalist being prosecuted for doing his job. It stands in marked contrast to how the Coalition responded to the situations of journalists Greste and Ricketson.

What do you think about the way the Morrison government is dealing with Assange’s case?

The Australian government’s conduct has been appalling. They don’t give two hoots about Julian Assange. They don’t care one bit about the principles at stake and the precedents that will be set.

For the Australian government, it’s almost entirely about Australia’s relationship with Washington, kowtowing to whoever is in the White House, and being prepared to line up with people like Mike Pompeo, who, being the former head of the CIA, just wants to get even.

It’s been dreadful behaviour. There has been a general reluctance for politicians to weigh in on this, because of the range of views in the community about Julian Assange personally.

But that’s also been dreadful to watch, because the public’s view of Julian Assange is largely based on misinformation and disinformation.

It’s up to politicians like me, and including the prime minister, to educate the public about the substantive facts of the matter.

This isn’t about Julian Assange’s personality. It is nothing to do with the historic and now dropped allegation of rape.

In fact, if you look at the very narrow timeframe that the US action is based on – from late 2009 to early 2011 – the substantive matter is that the US is guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and Wikileaks and Julian Assange published hard evidence of that.

That is what Morrison, his government and my colleagues should be explaining to the community.

Sure, I probably lost a bit of skin weighing in on this initially, but whenever I explain the substantive facts to people, they almost always come onside.

And lastly, Mr Wilkie, you’re saying that the government should set out the facts for the community.

But how else should the Morrison government be acting in regard to one of its own citizens? And if the Coalition did take those steps, would they be effective?

The obvious thing for Morrison to do is to pick up the phone to Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, and say to both of them that this has become a circus that’s gone on too long, so cut Australia some slack and let Assange return to Australia.

That’s what Morrison should do. He makes much of his relationships with these world leaders. Well, there’s no point having such relationships if you don’t use them.

They are relationships built at public expense only because Scott Morrison is the prime minister. They’re Australia’s relationships with these world leaders, not Scott Morrison’s personal relationships.

So, he should get on the phone. And would it work? Well, I don’t know for sure. But if he gave it a red-hot go, there would be a real chance of breakthrough.

AUTHOR

PAUL GREGOIRE

Paul Gregoire is a Sydney-based journalist and writer. This piece was originally published in the blog for Sydney Criminal Lawyers. Gregoire has a focus on human rights issues, encroachments on civil liberties, drug law reform, gender diversity and First Nations rights. Prior to Sydney Criminal Lawyers®, he wrote for VICE and was the news editor at Sydney’s City Hub.

1 Pingback