Text by John Stapleton. Photography by Dean Sewell.

Perpetrator of the Christchurch massacre Brenton Tarrant, 29, was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole on 51 charges of murder, 40 charges of attempted murder and a charge of committing a terrorist act.

On March 15, 2019, Tarrant carried out mass shootings at the Masjid An-Nur (Al Noor) and Linwood mosques after spending months planning the attack.

It was the first time anyone has been sentenced to life without parole in New Zealand. Tarrant is an Australian citizen from Grafton in New South Wales who moved to New Zealand about two years before the attack.

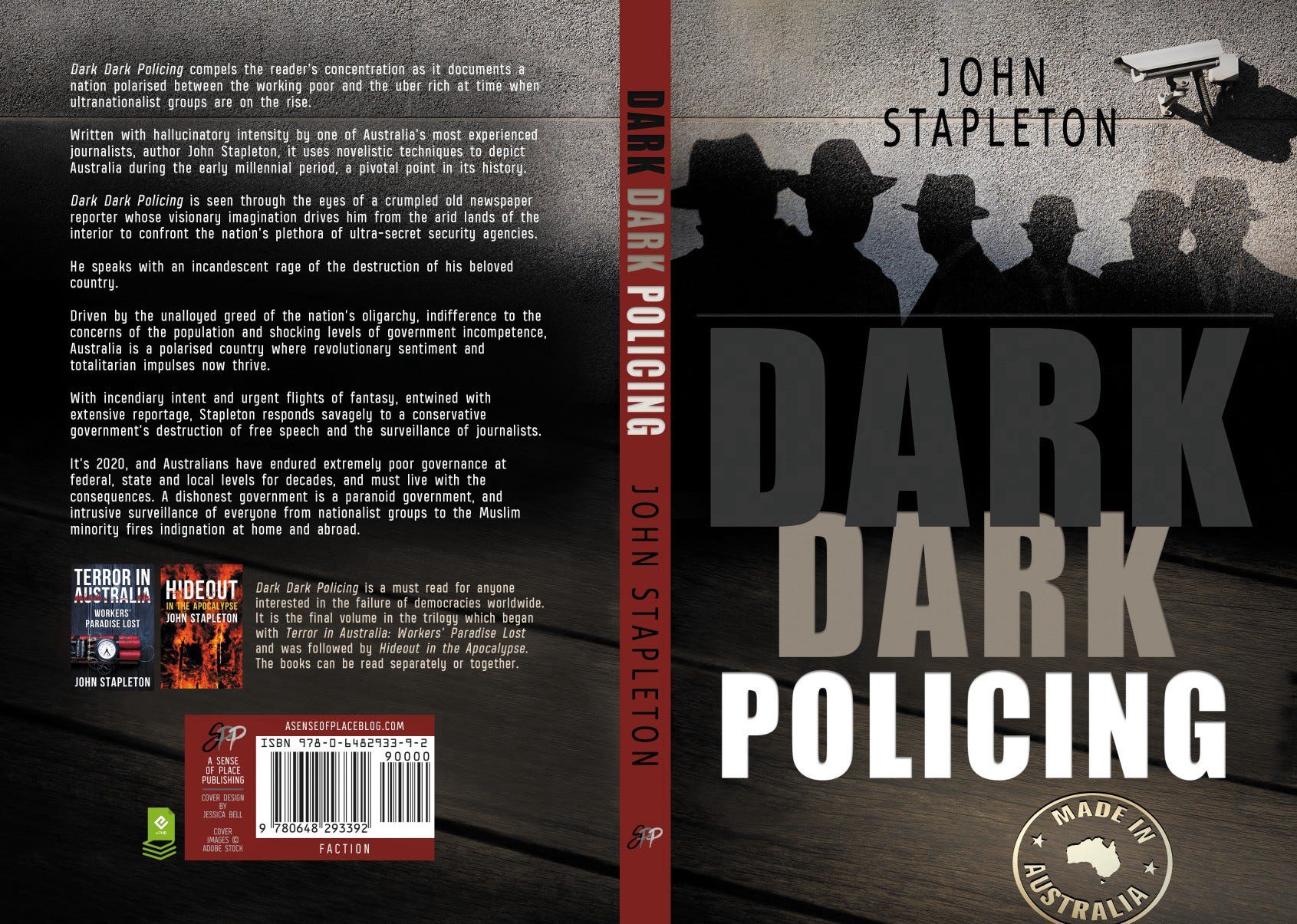

This piece is adapted from veteran journalist John Stapleton’s book Dark Dark Policing. It is a work uncannily appropriate for the current situation in Australian — an overwhelming sense of powerlessness within what is meant to be a democracy and the strong fear of an impending recession.

Nothing could be more volatile. Some stories are long in the cooking. Some turn on a single day. Some are erupting moments of long internal struggle.

Arguably one of the worst consequences of the widespread disillusionment in government that has flowed from the Abbott/Turnbull/Morrison era has been the rise of ultranationalism in Australia, the loss of a national identity and the splintering of any democratic consensus. With millions now being thrown onto the dole queues as a result of the Australian government’s panicked and inappropriate response to Covid-19, that situation is about to get a damn sight worse.

The live streaming of the Christchurch massacre to Facebook, perpetrated by an Australian citizen, 28-year-old Brenton Tarrant, broke new ground in online slaughter.

Terror, a kind of reactionary terror, had evolved.

As the New York Times recorded:

Mr. Tarrant now appears to have become the first accused mass murderer to conceive of the killing itself as a meme; it seems he was both inspired by the world of social media and performing for it, hoping his video, images and text would go viral.

“Just a ordinary White man” from “a working class, low income family,” Mr. Tarrant wrote in his manifesto. “I had a regular childhood, without any great issues. I had little interest in education during my schooling, barely achieving a passing grade. I did not attend University as I had no great interest in anything offered.”

Tarrant thought long and hard about the effective use of social media.

He wrote that in some ways his attack was specifically aimed at an American audience. In his Manifesto he recorded: “I chose firearms for the affect it would have on social discourse, the extra media coverage they would provide and the affect it could have on the politics of the United States and thereby the political situation of the world,”

And then came New Zealand. Facebook removed or blocked 1.5 million copies of the shooting video in a single day.

In the sea of analysis post New Zealand The New York Times noted that one surprising thing was how unmistakably online the violence was, and how aware the shooter was about how his act would be viewed and interpreted by distinct internet subcultures.

In some ways, it felt like a first — an internet-native mass shooting, conceived and produced entirely within the irony-soaked discourse of modern extremism.

The attack was teased on Twitter, announced on the online message board 8chan and broadcast live on Facebook. The footage was then replayed endlessly on YouTube, Twitter and Reddit, as the platforms scrambled to take down the clips nearly as fast as new copies popped up to replace them.

In a statement on Twitter, Facebook said it had “quickly removed both the shooter’s Facebook and Instagram accounts and the video,” and was taking down instances of praise or support for the shooting.

YouTube said it was “working vigilantly to remove any violent footage” of the attack. Reddit said in a statement that it was taking down “content containing links to the video stream”.

In its analysis NYT, fitting perhaps into its often orthodox left interpretation of the world, argued that online extremism was just regular extremism on steroids. The august news outlet argued that the only surprise was that anyone would still be surprised that social media produce this tragic abyss, for this was what social media was designed to do: spread the images and messages that accelerate interest, without check, and absent concern for their consequences.

There is no offline equivalent of the experience of being algorithmically nudged toward a more strident version of your existing beliefs, or having an invisible hand steer you from gaming videos to neo-Nazism.

The internet is now the place where the seeds of extremism are planted and watered, where platform incentives guide creators toward the ideological poles, and where people with hateful and violent beliefs can find and feed off one another.

So the pattern continues. People become fluent in the culture of online extremism, they make and consume edgy memes, they cluster and harden. And once in a while, one of them erupts.

The most common response to the Christchurch massacre in the Deep Suburbia the author now found himself was: “It’s a miracle it hasn’t happened before.”

The concerns of Australian authorities bear no resemblance to the concerns of the population.

Nothing in the official version of events and the piled on moral outrage allowed for a population’s rational response to irrational circumstances, to a polity which had betrayed a citizenry now fighting back.

Many people profit from chaos, witness the Middle East. Quell dissent, you encourage backlash. In Australia, one could swear the authorities were deliberately fermenting revolution.

Veteran journalist Paul Toohey wrote that Tarrant’s “Great Replacement Manifesto”, written two weeks before the Christchurch attack and designed to be read in the aftermath, ran to 73 pages and was a study in intolerance, hatred and the profound overriding fear that whites are facing extinction.

Disturbingly, it was also a document of the utmost single-minded clarity.

“Mass immigration will disenfranchise us, subvert our nations, destroy our communities, destroy our ethnic binds, destroy our cultures, destroy our people,” Tarrant wrote. “We must crush immigration and deport those invaders living on our soil. It’s not just a matter of prosperity, but the very survival of our people.”

Paul Toohey reflected that Tarrant was not a young man trying to solve a local problem. Far from it, the delusion was so grandiose that he saw himself changing the world. And, unfortunately, he had transformed a small and peaceful New Zealand city into yet another terror central.

Tarrant’s writing features language often heard among young men who gather in groups on weekends across Australia for intense discussions on the collapse of Western society at the cost of the supposed Muslim invaders, who produce too many babies and will drown us out.

These young men, like Tarrant, have detailed knowledge of the politics and the wars of the world. The knowledge quickly transforms into hard-boiled strictures of hatred, where anyone who disagrees is seen as weak and disengaged.

One group I met in a Victorian pub several years ago were most despondent that Australians were ignorant to the invasion in their midst. Tarrant likewise describes his fellow Australians as “apathetic”, showing interest only in “animal rights, environmentalism and taxation”.

Politicians and members of the public of all persuasions used the event to peddle their own interests and display tolerance, progressiveness or prejudice; or ludicrously in Australia’s case, an opportunity to purport to take a tough line on online extremism, as if the internet hadn’t been flooded with ultraviolent videos for years.

The blood drenched videos of Islamic State throwing “infidels” off buildings, burning them alive, dragging them behind cars, crucifying and stoning to death non-believers in a reversion to medieval practices, the high quality videos of ritual mass beheadings and masterful use of social media were all factors in their cut-through presence.

Extreme violence works.

Australia’s internet was so bad you were lucky if you could get online, much less be extreme about it.

Why these people thought such a technologically backward country could contribute anything, who knows?

A typical scene growing up in the unhurried streets of Grafton

This was a story which ran every which way.

As the SITE Intelligence Group’s well respected Rita Katz records, white supremacists celebrated the attack across various venues, from community-specific forums like Stormfront and Vanguard News Network to alternative, free-speech-purposed social media platforms like Gab and Minds.

Equally on platforms like Telegram messenger and Facebook, jihadists from around the world disseminated news of the shooting and called for revenge.

The subsequent Easter Sunday attacks in Sri Lanka in which 259 people were killed was seen as payback for the Christchurch attacks. Islamic State claimed responsibility.

From Australia’s great unwashed the most common comment was that the only thing surprising about the Christchurch massacre was it had not happened sooner.

Reap what you sow. Flood the population with foreigners, preference them in everything from government jobs to public housing whilst ignoring the outraged voices of the host population, the disenfranchised and those whose politically incorrect beliefs were entirely excised from the public square, and you have a recipe for revolution.

Didn’t matter how much the nation’s social engineers preached to the unconverted about racism, tolerance, inclusivity and diversity as a strength.

The Tarrant family are well established in the area.

The author, roaming in his old car up and down the east coast of the country, turned off the main highway into Grafton, where Brenton Tarrant grew up and for a while had been a bodybuilder and a personal trainer.

There wasn’t anywhere much more ordinary than Grafton; stop and ask directions and you quickly realise you have been caught in a time eddy, a place where time has slowed down. Asking directions, which would lead to a 30 second response in the city, could easily lead to a 20 minute conversation.

“You go about three miles out, there’s a big tree on your right, you can’t miss it… “

Or as The New York Times recorded:

Grafton is a peaceful and quiet eastern Australian town along the Clarence River, surrounded by farms and filled with families and retirees, a place where people leave their homes unlocked and everyone knows someone.

The biggest event is the annual Jacaranda Festival, named for the blossoms of its indigo-flowered trees. The biggest construction projects are the new jail and the new bridge.

So it was a stunner on Saturday for Grafton’s 18,000 people when they were involuntarily vaulted into the center of notoriety, as the world learned that one of their own was the suspect in New Zealand’s worst mass killing.

Senior writer at The Australian Paul Maley recorded that Brenton Tarrant was born in Grafton in 1990, the son of Rod Tarrant, a garbage collector, and Sharon Tarrant, nee Fitzgerald. The townsfolk rallied around the Tarrants, who were well known and liked in the Clarence Valley.

In the aftermath of Christchurch there was incredulity that such a heinous act could have its roots in a place such as Grafton, as if monsters must come from ghettos or war zones or dank basements.

If not Grafton, then where?

The Tarrants are an old family in the Clarence Valley. Rod Tarrant’s forebears settled in the area and decades later the phone book abounds with Tarrants…

Photographer Dean Sewell, who was on assignment for The Wall Street Journal, recalls:

The one thing that I came away from this job was that the community itself was very protective. We struggled a lot to get anything out of anybody. They all clammed up. They were very protective of the Tarrant family. It was in some ways surprising, but in small country towns they are protective of their own. And here, they were very protective of their own.

I had been in Grafton nineteen years before, on the occasion of the Olympic Torch touring the cities, towns and hamlets of Australia prior to the 2000 Olympics.

With the splendid news photographer Renee Nowytarger, I had already been on the road for days, and would be on the road for many more. I would occasionally release a stale pair of socks into the wilds of the Outback before purchasing another at a local shop; it was that sort of trip. Of Grafton and the Olympic Torch I wrote:

The jacaranda town of Grafton draped itself in 40km of purple crepe yesterday in one of the most spectacular welcomes the torch has received so far.

The pastoral centre pulled out all the stops, with every shop, house, streetlight, tree and fence along the torch route covered in bright purple. The town’s central roundabout was planted with purple flowers, and purple-and-lilac balloons hung from verandas. Some locals even dyed their hair purple.

The real jacarandas, with nothing but a few autumnal leaves clinging to their bare branches, won’t start flowering until October.

The most frequent comment he heard from the countless excited locals he interviewed as they followed the torch from town to town was: “It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity.”

Already, two decades on, it spoke to an innocence entirely lost, an Australia of another time.

For a feature piece on the experience he recorded being flown with a photographer to the twin towns of Albury Wodonga on the Victorian border on the Monday in mid-August that the torch entered New South Wales, now rebadged as the “Olympic State”.

The assignment to cover the torch relay for its first fortnight in NSW seemed at first little more than an excuse to get out of the office. The enthusiasm with which it was apparently being received in the countryside had little resonance for jaded Sydneysiders, who were on the whole slow to warm to the Olympics.

Hours before the torch was due the crowds began to gather, first in their hundreds, then in their thousands. The weather was miserable, cold and wet, and the evening celebrations had been moved from a sodden park to a giant car park. But nothing was going to dampen Albury’s enthusiasm.

It was then, interviewing some of the waiting crowd, that I first heard the statement I was to hear hundreds of times. “It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity.” As they spoke, four excited children watched their mother and father talk to a journalist. Indeed it was the excitement of the children around the state that helped make the torch such a singular, unexpected success.

The next morning the rain was bucketing down, but sodden runners carried the torch as if it was the greatest thing that had ever happened to them, as if it really wasn’t raining at all.

Through the downpours we headed off down the Murray. It was then, in tiny riverside communities such as Corowa, Yarrawonga and Tocumwal, that I started to get a sense of what it meant to these people.

For despite the rotten weather everybody had turned out in droves. And not just those in the towns, but everybody a hundred kilometres either side of the highway, and all their friends and relatives as well.

While in Sydney all you got was sneers about ticketing fiascos and the unappealing personality of Olympic Minister Michael Knight, here everybody wanted to be a part of it.

And almost everyone who carried the torch said much the same thing: “I am honoured and proud to represent my family and my community. It is one of the most exciting things I have ever done.”

Fast forward to 2019 and Australia was a very different place.

And Grafton had the world’s media crawling all over it.

As The New York Times recorded, members of the international news media poured into Grafton, 380 miles north of Sydney, rushing to find anyone who knew or remembered the suspect.

As Tarrant was charged in a Christchurch courtroom, many Grafton townspeople were stupefied.

“The town has gone into silence,” said Ola Williamson, the owner of a restaurant in Grafton. People had lined up to buy newspapers that morning looking at one another with shock. “I hope we don’t get tarred with the same brush,” he said.

As I started up the car and drove back to the main highway south there were young mothers playing with their children in a park nearby. The place seemed totally harmless. It was the ordinariness of it all that was the killer.

All photographs by Dean Sewell of Oculi collective.

This piece is adapted from the book by veteran Australian journalist John Stapleton called Dark Dark Policing. The book is the third in a series which began in 2015 with Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost and was followed by Hideout in the Apocalypse.