By Gordon Weiss

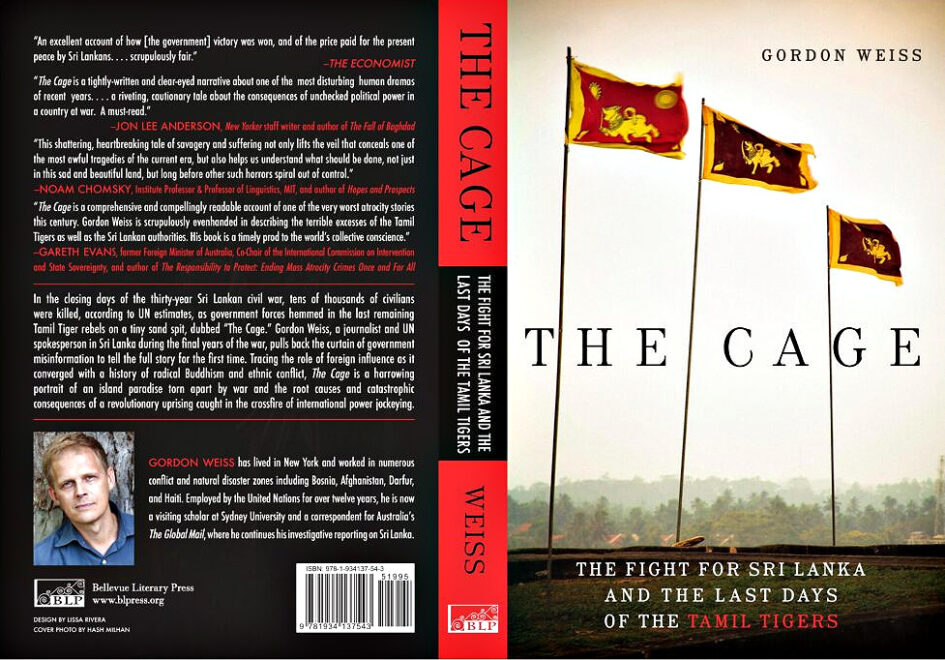

As the country is once again enveloped by social and political chaos, here with the kind permission of the author is an extract from the Preface for the American edition of The Cage, acclaimed as one of the best books ever written about Sri Lanka and an essential text in understanding the chaos now enveloping the island nation.

If I was browsing through a table of books, I would surely ask myself what on earth could tempt me to read a volume dedicated to a distant war fought on a small Asian island.

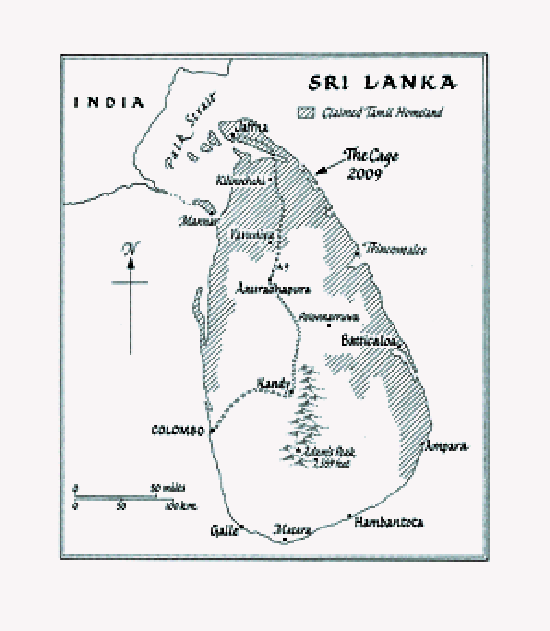

When the civil war ended in Sri Lanka on May 18, 2009, few knew what had transpired. To those outside the Sri Lankan circle of knowledge, the news sounded like a cause for celebration: the end of a 27-year-long civil war, the destruction of a ruthless terrorist organisation, and the return of a legendary island paradise to a state of peace. In our Age of Terrorism, this was surely a good thing. Weren’t we in the West engaged in the same kind of struggle?

Just a month after the war, the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva resolved to praise the government of the island nation. But in March 2012, a very different US-initiated resolution was negotiated through the same body.

This time, prompted by public outrage over evidence of war crimes, the US and 23 other nations resolved to discover what had really happened in the months leading up to the final day of fighting. Between these two resolutions much had changed.

For years, the government of Sri Lanka had promoted their version of events. It was, they told their people and the outside world, an unprecedented “historic victory.”

Their freeing of almost 300,000 Tamils from the control of the Tamil Tiger rebels had been “bloodless”; moreover, it was “the world’s largest hostage rescue.”

They touted a set of anti-insurgency principles that had governed the campaign, and even offered to train the US military, struggling in Afghanistan.

Then, inevitably, contradictions began to emerge. There had always been rumours coming from the vanquished Tamils. Stories of mass executions; government forces targeting civilians, hospitals, and schools; prisoners taken in the dead of night from refugee camps after the war, whose silent removal became permanent disappearances. But now there was fresh, compelling evidence that ran roughshod over government claims.

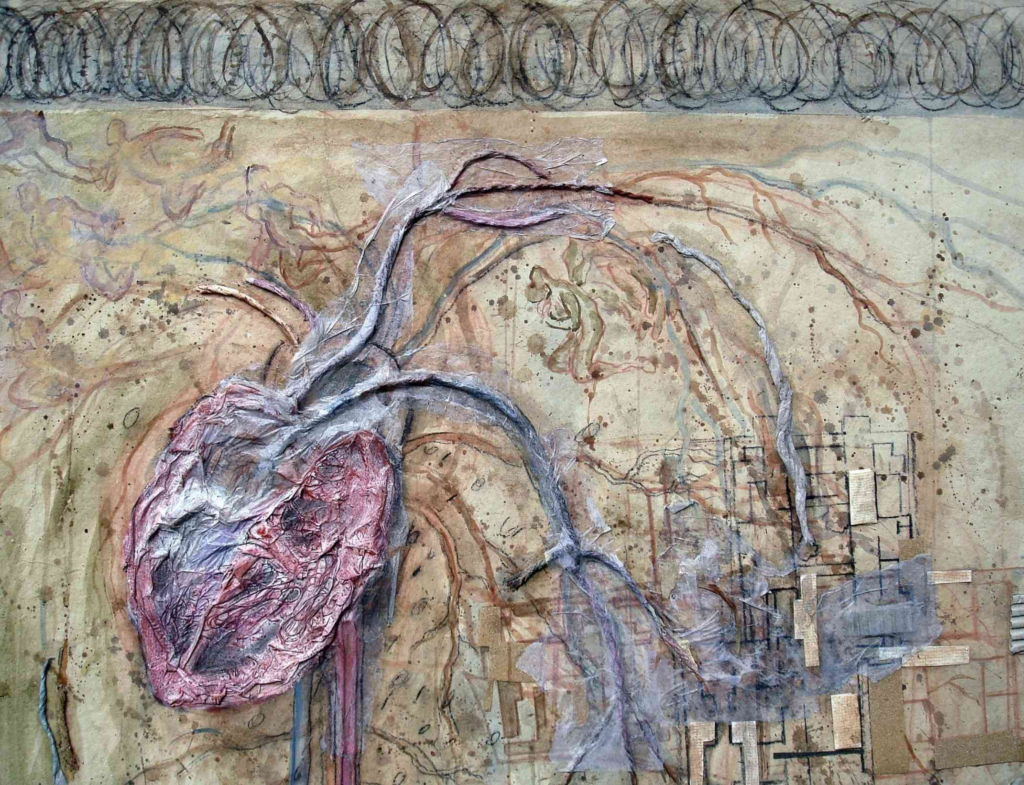

Tamil artist Sanathanan Thamotharampillai is recording memories of survivors of Lanka’s civil war

Young Sri Lankan soldiers had unwittingly documented their crimes. These troops did what is increasingly common among today’s soldiers: they had used their cell phones to film scenes of civilian and combatant executions. These trophy videos were passed from phone to phone until, inevitably, they reached the hands of journalists. A series of US diplomatic cables revealed during the Wikileaks scandal added to the evidence.

The government of Sri Lanka responded with well-rehearsed bluster. After all, during the war its President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, had personally assured US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that his government had done all it could to protect civilian life. If there had been any civilian deaths (a point the government did not concede for a long time), it was the doing of the Tamil Tigers.

Indeed, with a well-established record for ruthlessness, as well as solid evidence, it was conceivable that the Tigers had killed many of their own.

The government claimed that the videos and photographs had been faked, the tricks of a global Tamil conspiracy. They pointed to Sri Lanka’s well established democratic institutions, such as its highly developed judiciary and police force, and to a long series of judicial inquiries, as evidence of a sovereign nation fully equipped to investigate and punish any wrongdoing. In doing so, however, they pointed to the very cracks in Sri Lanka’s modern nation-state edifice that had led to the bloody outcome of 2009.

The Cage tells this story. It lifts the veil of deception that enveloped the fighting, reconstructs just how the war and alleged war crimes unfolded, and argues that the body of available evidence will compel the international community—led by the US—to act. It delves into Sri Lanka’s ancient past to explain the present, describes democratic institutions that no longer function, and shows that under the Rajapakse brothers, the island today is governed by fear.

It is a government that is so cocksure of the efficacy of its thuggish rule that it seems blind. When it arrived in Geneva prior to the March vote this year, its 71-member delegation included intelligence operatives who harassed Sri Lankan human rights activists under the noses of other international delegates. This crass display of contempt for due process influenced India, hitherto a rock solid opponent of action against Sri Lanka, to vote in favour of the US-led resolution.

One reason the UN Human Rights Council passed Resolution 19/2 is because few now believe the Rajapaksa government is willing to account for the past. Not only had Sri Lanka demonstrably deceived international leaders, it continued to do so. In late 2011 it produced a seemingly erudite investigative report that whitewashed possible chain-of-command responsibility. Now, in early 2013, the government must return to the same UN body to argue, in effect, why there should not be an independent international criminal investigation.

Beyond the political interest to a US reader, however, lies the vast human tragedy that is Sri Lanka. The story of the island nation is inherently interesting because it is set within an ancient island civilization, recommended to modern travellers in its post-war era as the 2010 go-to vacation destination by no less than The New York Times. Yet the smiling face of Paradise Island conceals an excruciating story of bloody mayhem—a story that the conscious and purposeful traveller ought to be aware of.

Sri Lanka has much to teach us about our past and present. Violence has been cyclical on the island nation for more than four decades, when the first of a series of great civil bloodlettings began. There are literally many tens of thousands of murders for which nobody has ever been held to account. Millions of Sri Lankans alive today—Tamils and Sinhalese—have direct experience of the terrible phenomenon of “disappearance,” and an abiding sense of injustice and unreconciled grievance.

Peace, and peaceableness, so central to Buddhist practice, does not sit easily at the heart of the island’s polity. Nor does reconciliation. Yet since the end of the war, the government and its supporters have consistently maintained that they should not have to account for allegations of criminality.

Its postwar PR blitz has included a documentary called Lies Agreed Upon; a comprehensive report issued by the Sri Lankan military; a full commission of inquiry report; and most recently, a book authored by a Sri Lankan journalist titled Gota’s War. All these devices are calculated to obscure consideration of civilian deaths.

In this regard the last, which confirms beyond doubt the command responsibility of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and provides a useful account of the disciplined and clever campaign fought against the LTTE, is better read for what it omits than what it includes. Rather, the government has branded international pressure to provide a plausible account in answer to allegations of war crimes as both a plot by the rump LTTE (whose political interests any investigation, as a by-product, might unfortunately also serve), and an attack on the government’s sovereignty, an argument that instinctively appeals to postcolonial nations that form a majority in forums like the UN Human Rights Council.

Furthermore, the Sri Lankan government has insisted that scrutiny of the past threatens efforts to promote reconciliation. The Rajapksa government has been particularly adept at deploying the pleasing notion of reconciliation in service of its political and personal agenda.

Under the guise of development, the Sri Lankan government is using its army to control the economy of Tamil-majority areas, and to change the demography. Rather than justifiable security precautions and policing, its writ is characterised by disappearances, sexual violence, and a menacing presence to enforce a programme of exploitation. Under such conditions reconciliation remains, at best, notional.

As convincing evidence of criminality has continued to emerge, and reconciliation has been stymied by the army’s unhappy occupation of Tamil-majority areas, many Sinhalese—good, humane, and conscientious people—who supported the war, have grown uneasy. Quite simply, they did not ask that crimes be committed in their name. Most Sri Lankans will not want a war crimes process but are left wondering how to move forward, particularly given the state of reconciliation.

After Resolution 19/2 was passed, T. Aruna wrote in the respected online Sri Lankan journal Groundviews: “It’s not a stretch to say that there is blood on all of our hands…We all bear some degree of responsibility for the commission of atrocities, even in our failure to oppose them in deed or thought. Each of us has sustained the war machine in some way—I know that I have…it is not a defence now simply to say that we did not know. If we wish for others to atone for their sins and omissions, then so must we.”

Originally published 15 July, 2022.