A Sense of Place Publishing’s author Dr Stephen Edwards is once again front page news in his home state of Tasmania.

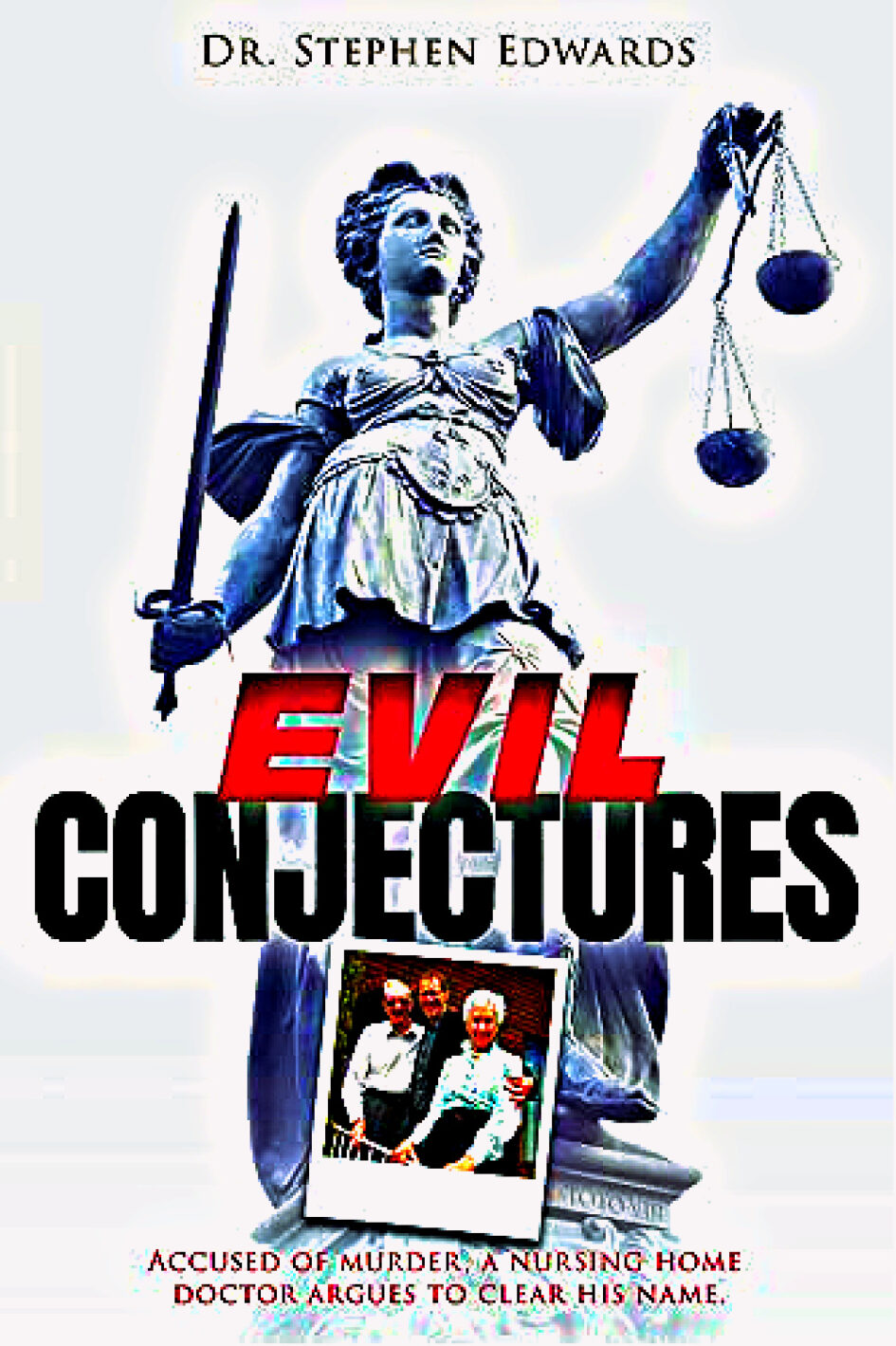

Arguably as a result of the widespread publicity surrounding our publication of his moving book Evil Conjectures, which delves behind the scenes of his being charged with murdering his mother and his time in jail, the Tasmanian coroner has opened an inquest into the death of his parents.

One of the first steps in the extremely muddy case has been the request by Dr Stephen Edward’s lawyers to separate the case of his elderly father and his elderly mother’s deaths, which became conjoined in a case which provoked considerable gossip and “tittle tale” evidence.

The terminally-ill former Hobart doctor says an upcoming inquest into the controversial death of his elderly Sandy Bay mother should not be bundled together with his father’s death.

No one, least of all Stephen Edwards himself, who has terminal cancer, expected to see him alive in April, 2023, able to attend last November’s launch of Evil Conjectures, and now a long overdue coroner’s inquest.

If you Google ‘Dr Stephen Edwards’ you will find news stories of him allegedly murdering his elderly mother, being sent to jail for three months and then on bail for four years until the case was dropped.

Edwards, a former general practitioner who specialised in nursing home patients and palliative care, was deregistered after the charge of murder of his mother was brought against him. The case was closed after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer and given six to thirteen months to live in January 2020.

The story of how Edwards was charged with conspiring with his brother to murder his mother confronts the most fundamental questions of life and death, magnified by his own diagnosis of terminal cancer, which he stubbornly refuses to accept.

Remarkably, as of November 2022 he remains alive.

His incarceration in Tasmania’s most notorious high-security jail brought him into direct contact with mass murderer Martin Bryant as well as the inequities and perverse injustices of the prison system.

Dubbed ‘Dr Death’ by his fellow inmates, he nevertheless earned their respect. He was only the second person in Australia to be granted bail for murder, and his treatment highlights the lottery that is the justice system. Perversely, the dropping of the charges against him makes it impossible to clear his name. His narrative of the events that led to his murder charge and his fight for justice makes for compelling reading.

Here is an extract from Chapter Four: Jail Time.

This is the latest book from A Sense of Place Publishing.

What was it like in prison? ‘Did I get bashed or abused?’ people ask, in hushed voices. Not knowing if or when my release was coming was the hardest thing. Would it ever end? My legal team were suitably optimistic.

All the big and little ways that prisons work to dehumanise the inmates belongs to a Dickensian world long overdue for radical reform. What percentage of the jail population was like me, awaiting judgement? On remand, if you don’t get bail, you’re presumed guilty. The court backlog means that cases may not be heard for two years or more. By the time the prisoner goes to court the term of incarceration in the sentence may have already been served. The official response? Tough.

I spent my first six weeks in the Mersey unit, a high suicide-risk, high-observation block, seventeen cells with a rolling population of the mentally unstable. It took three weeks for me to lose my pompous indignance. An old hand took me aside in the common area and paced with me in the exercise yard. Don’t rattle the bars, he would say. Play along. How are you today? Living the dream!

Although his neighbours hadn’t been fond of him mowing his suburban lawn in the middle of the night, he had somehow survived ice and was neither unhinged nor drug-fucked. Always with too much energy, he told me that when he was at school his teachers would give up and send him outside to help the gardener. He learned to read and write on his first stint inside playing Scrabble.

This time he was in prison accused of the murder of another ice dealer. The criminal he took out was much hated by the police, who were keen to protect my new friend from other inmates affiliated with his victim until the case went to court. The funny-bin was, for him, a safe refuge. He slept well.

The groans, screams and other anguished cries of the criminally insane locked in their small cages would echo around the bare walls of the barrack most nights. We would wake to animal howls, then the bashing and crashing noises, then more screams as the guards arrived, sounds of a quick scuffle, then a muffled exit to one of the three padded cells in the compound provided for their comfort. There were some guards who, it was clear, enjoyed these nightly rituals. When called to strong-arm a distressed resident by day, their laughter and bonhomie were disgusting. We all looked down.

Those who had not slept so well were given distance when the cell doors opened in the morning and we moved into the common area. Milling around the toaster and microwave when breakfasts arrived, wry comments would be made about whoever had gone off in the night. It was often ice addicts who needed a week after arriving in prison to withdraw from the drug and find whatever level of brain function remained. Fourteen days, my friend advised. After not sleeping for over fourteen days your brains are permanently fried.

The revolving door of Risdon Prison does nothing to prevent this cycle of self-destruction. Perhaps a prison farm would be more helpful than incarceration? Then there are all the victimless crimes. Marijuana cultivators, known as croppers, are a good example. How much does it cost to lock them up to do hospital laundry? I heard between four and five hundred dollars a day. Perhaps a prison farm would be more appropriate?

During my stay in the loony-bin I had regular meetings with the mental health team when I would rage against the system, the lack of access to the prison library, a two-week delay before my partner Jamie could be approved for phone calls, having a torch shone in my eyes every hour overnight through the cell door to ensure I hadn’t topped myself. I ranted at them in high dudgeon, outraged, innocent, frustrated and furious.

Hearing the personal stories of my (erstwhile) companions made me feel less self-important. Although I protested my innocence, my fellow inmates assumed my guilt which gave me unexpected kudos. Murderers sits at the top of the criminal hierarchy. At the bottom are the paedophiles, who have to be housed separately in their own barracks for protection from the other inmates and known as tamps (those who tamper).

The first question to newcomers is, ‘What are you in for?’ My story spread quickly. Soon, people were addressing me as Doc or The Doc. I played along and would do crazy faces. It would get a laugh. I had been handed an easy persona to maintain which, as an older and much affected man, saved me from any other abuse when moved to the general prison. My friend would say in company, in a way I found charming and disarming, that I couldn’t kill anyone without a script pad. When a young inmate informed me with a snigger that I was a sick cunt, it took me a moment to realise he was complimenting me.

13 May 2016: Random acts of injustice reduced us to insolent animals.

A new prison director had been appointed, a reformer from the UK who produced an agenda to lead the jail into a bright new future. The guards objected, the system groaned and each item of reform was stymied by the this-is-how-we-do-it-here attitude, the keep-your-smart ideas-to-yourself response. If it kind of works, leave it alone. It’s a Tasmanian thing, our ball and chain.

At unlock time a few mornings ago one of the guards said to me, ‘How are you today?’ To which I replied, ‘Well, I’ve got no newspaper, no books and I’m surrounded by brain damage.’ To which another guard laughed, ‘Yeah, you’re in jail now.’

‘That’s about it,’ I snapped back, trying not to spin on my heel or storm off.

Checkers and chess were popular and, yes, I did play checkers with Martin Bryant, where again I was trounced despite the high levels of medication he was on. A docile animal who often had to be coaxed from his cell in the mornings, he had a history of repeated self-harm. Time spent in the prison hospital resulted in a stultifying drug cocktail which removed his ability to commit suicide and rendered him almost mute.

Still, new inmates would get him excited with questions about where to buy guns and which ones he liked. He was not tall. The drugs and prison diet had increased his weight. Recent recognition in the visitors’ centre with his mother on his birthday led to abuse and food-throwing from other inmates. Since then, he has shaved his long, curling, blond locks and now looks like a stumbling Tweedledee who could still wipe the floor with me at checkers.

Diary Entry: 18 June 2016: I keep my face closed, my voice low and expressionless. I do not exist. I am no-one. Twelve days till hearing …

Smoking was banned in the prison to protect the health and wellbeing of both inmates and the guards, who were ruled by the same regulations regarding nicotine as other government employees. The prisoners strongly opposed the ‘No Smoking’ edict, but were unsuccessful – a great blow to many chain smokers. So, necessity is the mother …

Grass from the lawns, or fruit and vegetables, or the lettuce from my salads were initially in high demand – until I got wiser. The grass or food scraps were dried in the microwave or sandwich maker to provide a vehicle to absorb the liquid extracted from soaking used nicotine patches. Wrapped in paper and lit with a spark from batteries, these prison cigarettes were popular, and newbies would be encouraged to go on the patch to ensure a continuing supply. Often in the afternoons, a tired guard’s voice would explode from the intercom:

‘Will the prisoners on the back lawn please stop picking the grass.’

The question people don’t ask about my time in jail is this. Did it change you?

The answer is yes. Oh yes. Yes. YES.

But how?

Don’t fuckin’ ask!