By Paul Collits.

Australia’s ruling Coalition of the Liberal and National Parties is now mired in scandal so deep they are facing electoral oblivion. The tremulous leadership of current Prime Minister Scott Morrison is dragging down the conservative brand; and tensions are high.

When this period of Australian history is written, academics will pick over the detritus of the ruling elites in an attempt to understand how a party which was meant to stand for probity in public office and encourage independence and common decency in the population came to be captured by bureaucrats and their multiple tertiary acquired agendas, none of which resonated with the people they were elected to represent.

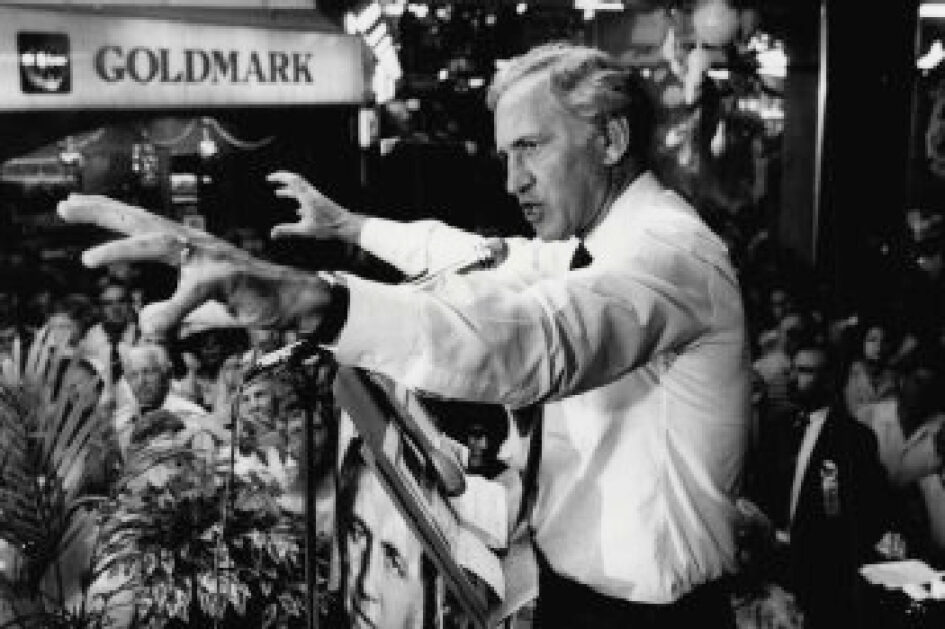

Former Liberal Party Leader and Australian Foreign Minister between 1885 and 1990 Andrew Peacock has passed away, aged 82, at his home in ,the US. The event was accompanied by glowing tributes, inevitably, “great Australian”, from the political class, present and past.

But how good was Peacock? And what, if any, were his achievements?

Will the souffle rise thrice? In death, the late Andrew Peacock has achieved much respectful praise.

It was Paul Keating who cruelly, but perhaps accurately, described Andrew Peacock’s second coming to the Liberal Party leadership in 1989, as proving that “a souffle can rise twice”. Well, knowing Keating’s own limitations, it was probably my late brother’s great cricket mate and Keating speech writer Don Watson who suggested the line.

Peacock’s passing has brought forth a range of eulogistic commentary, much of it delivered with, alas, rose-coloured glasses. All the usual suspects have had a go. Many of them aged warriors from another, twentieth century time when our politics were, like the past itself, a different country. Names that, for those under forty or so, will mean not very much.

The most immediately apparent and unstated characteristic of the eulogies has been that they amount to an unmistakable pitch – that Andrew was a “great Australian”, a wonderful “public servant”, a serious diplomatic player, and a gift to the development of the Liberal Party.

Really?

What is going on here? Leftie pollies, both within and outside the Liberal Party, see Andrew’s passing as an opportunity to stick it to conservatism. That battle never, ever ends.

They say, never speak ill of the dead. Fair enough. But our duty as analysts of these things is not to falsely praise the departed, just because they are departed. Perspective is indicated, I would think.

Andrew Peacock led the Liberal Party through one of its least successful periods. Perhaps through no fault of his own.

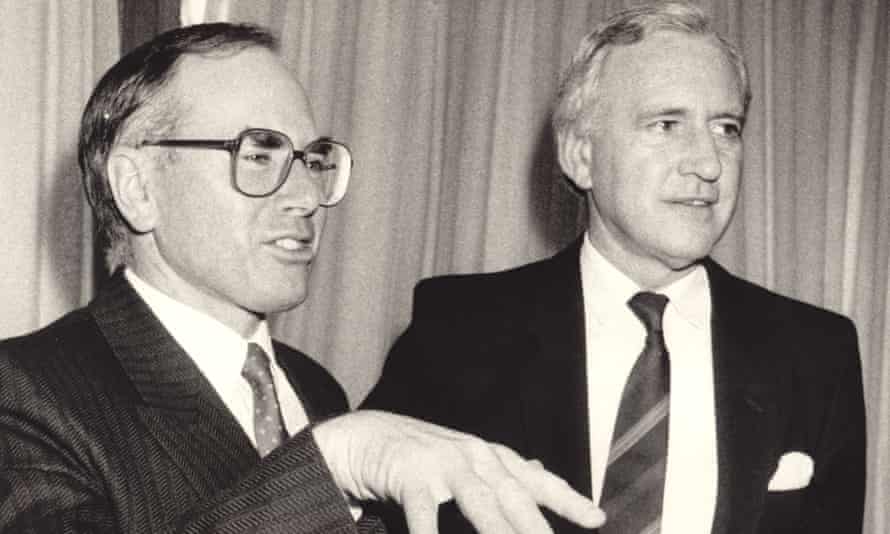

Peacock was not leaderly, nor was he much interested in policy development or economics. His (two, unsuccessful) tenures were associated with electoral failure and internal party animosity bordering on civil war. He lost elections. His Party’s progress during this period – for example the movement towards rational economics, a focus on policy reform, cleaning up the hideous corporatist industrial relations club and the acceptance by the Opposition of the Hawke Government’s economic reforms – was totally down to his then deputy, one John Howard. Howard provided pretty well the only headway that occurred over the decade or so of the Peacock wars.

Admittedly, Peacock’s occupation of the Liberal leadership coincided with the majesty of the populist Hawke, truly an outstanding leader and an unassailable political opponent in his pomp. This was Peacock’s fate. And Peacock’s tenure coincided with an ideological civil war within the Liberal Party. (Though, to be fair, has there ever been another state of the Liberal Party)? Again, not Peacock’s fault. But he was singularly inept at managing the rise of the Dries (neo-liberals) who had no particular argument with Peacock personally, but whose appearance and ideas demanded resolution.

It is easy to characterize Peacock as a Liberal “wet”. Not true, in fact. He was actually a pragmatist with wet leanings and instincts. Like Howard was a pragmatist with “dry” leanings and instincts.

But Peacock never worked out a way of resolving the internecine wars. That task remained for Howard, in government, to achieve. With considerable aplomb, as it happened. Howard never resolved the ideological war, of course, but he managed, at least, to run a government with success over many years in a way that Peacock, whatever his current champions may suggest, never could have.

The Adelaide Advertiser suggests that Peacock was the “best prime minister we never had”. On what basis they suggest this, I have no idea. Other candidates suggest themselves. Their claims outweigh Peacock’s by a fair stretch.

I was there in the mid-1980s, up close and personal, when the Howard-Peacock wars were taking place. It was not pretty. It was civil war.

One of Peacock’s lieutenants, the unlamented Chris Puplick, maintained a picture of Peacock on his office wall right the way through Howard’s initial tenure, until he and others – whose names would not mean much to current readers and whose contributions to Australian politics were meagre at best – decided on the regicide option in 1989. Alas, Peacock’s second coming at the expense of the ruthlessly dispensed John Howard led to nothing.

Zip.

No resolution of the Liberal Party’s civil war, and no electoral success. Peacock’s second failure led to the brief and disastrous tenure of John Hewson, the “visiting professor”, as Paul Keating (again) dubbed him. Then there was Alexander Downer … In terms of party leadership, enough said.

The Liberal Party’s endless internal wars are always about people-factions as well as ideas.

Peacock’s home base was Victoria, that bastion of “liberalism” – the jewel in the Liberal crown, as political scientists used to say. The Deakinite South. Deakin, like Peacock, was a moderate liberal hero. Ironically, moderate liberalism has found its twenty-first century home north of the Murray, in Macquarie Street.

I briefly encountered Andrew Peacock on the night of the 1984 election, where he took seats off the then apparently unassailable Hawke Government. I was an Electoral Commission official. Up close, Peacock was tense and grumpy, and not especially personable. His performance at that election was actually his best performance.

After that, it was all downhill. He was gone within twelve months, defeated in a bizarre leadership standoff with an ascendant John Howard. Peacock was hopelessly out-classed and out-flanked by an opponent who wasn’t even running for the top job.

Peacock’s supporters were not at all honourable in defeat, in 1985. They proceeded to undermine Howard at every turn. Again, it was not pretty. Whether Peacock himself personally orchestrated all these seedy shenanigans, who knows? Four years later, the relentless campaign had achieved its objective. Absent this vicious subterfuge, we might have got Howard as prime minister much earlier, and more effectively, than we did.

Peacock had sought to attain the highest office much earlier (1981). He was one of those, like Malcolm the Second, who seems to have seen himself as “born to be prime minister”, without knowing why this mattered, to him or to anyone else. He took on Malcolm Fraser, the incumbent prime minister. He was over-ambitious, even then. The leadership challenge was without much ideological intent, typical of Peacock, then described with some prescience as a dilettante. Malcolm Fraser was himself by then a pretty rabid leftie, after all.

Despite what Fraser’s then Labor opponents said of him, back in the day of the Whitlam Government. It was a challenge without meaning or purpose, other than to aggrandise Peacock personally. The colt from Kooyong, the prime minister in waiting.

Peacock’s Liberal Party daughter, (philosophically speaking), must be Maryse Payne, another Foreign Affairs Minister of indeterminate skills and a still-to-be-ascertained contribution to the national interest. Peacock with a dress. One who cherishes relations across the aisle, the soft inconsequential plays of diplomacy and international relations. Policy as process. Endless process. Without end, amen.

Liberal wets cherish reaching across the aisle above all else. Peacock’s ideological successors, like the man himself, have not the remotest sense of participating in an ideological culture war, or, indeed, their role in it.

Andrew Peacock’s story does not end, though, with his confused and much debated contribution to the Liberal Party during his tenure. There is a much happier postscript. He has been an exemplary ex-leader, in serene retirement. He has said little. He moved on, with grace and blissful silence, living in another country.

He was, it seems, a successful and certainly a well-informed Ambassador to the USA, a fact much acknowledged by John Howard and others. He found a way to be an ex-Liberal leader, a way that others, including some of his admiring successors, might have emulated (but didn’t).

Perhaps we should leave the last word to the man who Peacock replaced as the Member for Kooyong. Upon hearing Peacock’s maiden speech, Menzies is reported to have remarked that the speech was both brilliant and original. Unfortunately, he said, the original bits weren’t brilliant. And the brilliant bits weren’t original. Oh dear.

In the face of a tsunami of glowing tributes and rose-coloured memories from all manner of friend and foe, we might reflect on whether Peacock’s career ever rose higher than that underwhelming (to Menzies) initial effort. Or perhaps one might be tempted to paraphrase the fictional Sir Humphrey Appleby, who wondered whether one of his colleagues was indeed a high flier as reputed, or merely a low flier supported by occasional gusts of wind.

Rest in peace, Andrew Peacock. But, please, with realistic memories.