From Michael Gray Griffith: Café Locked Out

In the Kimberleys, I saw the broken backbone of a mountain range—time had spent millions of years pruning it down to here.

Its rocks were cracked and angry, too hot to touch, for the sun was using the entire landscape as an anvil to cook everything into submission.

I saw a thin line of trees bent into a dry creek bed as though time had frozen them in their last, desperate search for water.

I saw crows, like the living shadows of the birds they chose to escape from, overlooking it all, like Princes waiting for their Cook, Death to serve up today’s meal.

There were broken ballerinas, dressed as kangaroos laying on the side of the highways, with more ants and flies dining upon them, than there were stars forever flooding this endless sky with questions.

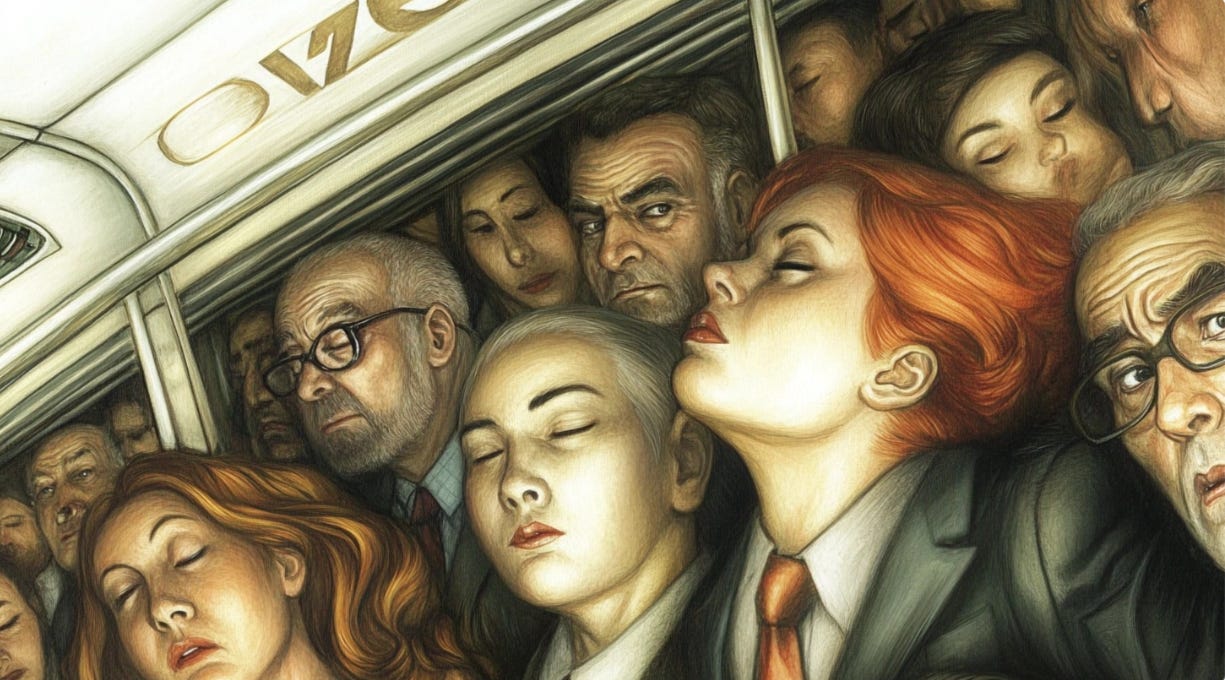

This land will kill you. Suburban man. This land, which is your land, Australia. It’s waiting out there for you. And you know it. Every time you’re squashed into a bus, heading to a job that you know is killing you, you can feel it. And you want to go too, for dangerous or not, you know she wants you, whereas this concrete jungle has, as yet, not even realised you are here.

The first white people to come out here built churches from the cracked stones.

Fringe fortresses for God, where they taught the black people how to be ashamed of themselves.

Because shame is how you defeat a people.

Rather than rising up, they’ll stay silent, trying to hide their regrets and pain in the grog or the drugs, until the rage escapes and sees them break the houses they live in, the cars they drive, and the people they love, until…

Too often, their lonely souls suggest a more permanent escape.

Same for the other races now, as the corporations make it clear—

With their policies that, despite all the freedom this harsh land has to offer the brave, you are a slave.

If you say something or post something they don’t like, they’ll sack you.

And then, even if, in an effort to show them you are a dedicated and valued employee, you keep everything offensive inside your mouth, they will discard you—

With all the pomp and circumstance a road train offered that kangaroo.

I once sat at a public table, near a trio of painted silos, and watched for a few hours as these discarded men, in their shorts, t-shirts, and obese bellies, parked their four-wheel drives and caravans.

As their bored wives watched, they took pictures of the silos.

For who?

Would they look at them again? Would they show their grown kids?

Would they even wonder, why am I taking this?

Or is it for those they left behind at work—evidence that they were free?

Many of them were born here, some are several generations old.

Yet if they parked out here, near the last of this mountain, and walked off into the desert, the land would take them.

But the black man lived out here.

He saw the land, for it was—is—his mother.

He can read the hard ground for the clues to where life, where food, is hiding, as his woman dug up sustenance from the baking earth.

But not our tourist.

That’s why he spent his life in the city, hunting for sustenance in fast food venues and shopping aisles.

Why he spent the best part of his life paying off bricked-up air—

Creating a cave from a shed, filling it with the greatest discoveries he’d found, his best kills—

A fish.

A signed jersey.

Within the concrete forest we built ourselves—

Only to become its seasons.

We are the weak ones.

We are the ones who take the abuse—who whine if our abuse is not recognised.

We are the ones who scan our own groceries so the supermarkets can make more obscene profits, as our kids look for work.

We are the generation that future generations will curse—

If they ever talk about us at all.

The generation whose most famous battle was for toilet paper.

The generation that forgave those who violated them by stating, it’s all over now.

It’s gone back to normal.

Except in this new normal—

You can die of cancer in a week.

A baby can be aborted within sight of birth.

And if it survives—this gift from the gods—

We’ll leave it to die, without painkillers, on a bench in a hospital room most would avoid.

We use the word safety as though it meant bravery, and we rarely use that word anymore.

We are the ones that, if God could, He would reread His blueprints and ponder—

How did a generation I gifted with so many virtues lead such inconsequential existences?

Then wonder why their suicide rate is so high.

We are the generation that stayed silent as they built the prison around us that we knew would be used to imprison them and their children. We could have been Humanity’s Liberators.

A face in a future, famous mural, a homage to love and courage and freedom.

Did you reach this far?

Are you pissed off?

Do you want to find me, tell me off?

Maybe punch, or hurt me?

I hope so.

I hope that somewhere inside of you, the stallion, you helped them break—

So you could get a job as a pony—

Is snorting.

Attempting to blow out all these years of bridles and saddles and ropes—

Until, with fresh free air in your lungs—

You’ll realise your soul has been waiting to perform its one trick…

Redemption.

You are not a number in a corporate system.

That is your chain.

A chain you are voluntarily locked in.

You are, instead, the most remarkable of creatures.

A child of the gods—able to create new people or kill them.

It’s your choice.

For if you put all your liberties into one pan, you could reduce all of them down to the core freedom you were born with.

Choice.

And currently, our society is slipping into a world where the powers that be are determined to steal that core freedom from you.

And these last few years have shown them that it’s possible.

What need of a God then, huh?

What need of a God when you have already chosen a master?

Greatness is not a destiny

It’s a choice

And even deciding to strive towards greatness

Is greatness in itself.

Currently humanity is under attack

And the meek can’t save us.

What we need is an army of greatness

So choose well.