By Nicolas Rothwell. Extract from Quicksilver.

Nicolas Rothwell is one of Australia’s most exceptionally beautiful writers; his lyrical prose and depth of intelligence making him a unique figure in Australia’s literary landscape.

He was the child of Czech and Australian parents. His father Bruce Rothwell was a prominent journalist, and the family resided in Australia, Washington DC, and New York among other places. Rothwell attended boarding school in Switzerland and France, and graduated from the University of Oxford.

In the 1980s and early 1990s he was a foreign correspondent for The Australian, a paper owned by his godfather Rupert Murdoch, and reported from the Americas, the Pacific and Western and Eastern Europe, latterly during the Yugoslav conflict.

Burned out by the latter upheaval, in the 1990s he sought out a posting in Australia, again for The Australian newspaper.

His extraordinary coverage of aboriginal Australia and his deep and abiding affection for the country, his penetrating analysis of the entire troubled and complex field of indigenous affairs, won him Australia’s highest journalistic gong a Walkley Award in 2006.

It is unfortunate that much of this body of work is hidden behind The Australian‘s paywall and little known to the current generation.

His books include Most recently Red Heaven, Quicksilver, which won him the Prime Minister’s Literary Award, The Red Highway, Another Country, Wings of the Kite-Hawk and Journeys to the Interior.

This extract has been produced with the kind permission of the author.

The primal order of the world has been shattered, it lies in fragments; the sparks of the divine are spread over the expanses of the earth, and it is essential to gather them up, each last scintilla; to go down into the darkness where they are disseminated, down into the furthest reaches of the world, and there embrace sin and falsity. Such paradoxes had a natural appeal, in a time when the adherents of the faith were constantly persecuted; when established rituals brought nothing; when God’s protection had so manifestly failed. It was this climate of ideas that paved the way for the religious cataclysms ahead.

***

In the summer months of 1937 Captain Leo Frobenius, the great impresario of German imperial ethnography, was on holiday at his villa on the shore of Lago Maggiore, planning his last expedition.

Frobenius, whose chief interests in life were espionage, absinthe and black women, had conceived the idea that the Kimberley region of North-West Australia could serve him as a window onto the fast-vanishing primeval past of man. Its corpus of rock art of varying styles, which was then being described for the first time by missionary researchers, was the focus of his attention.

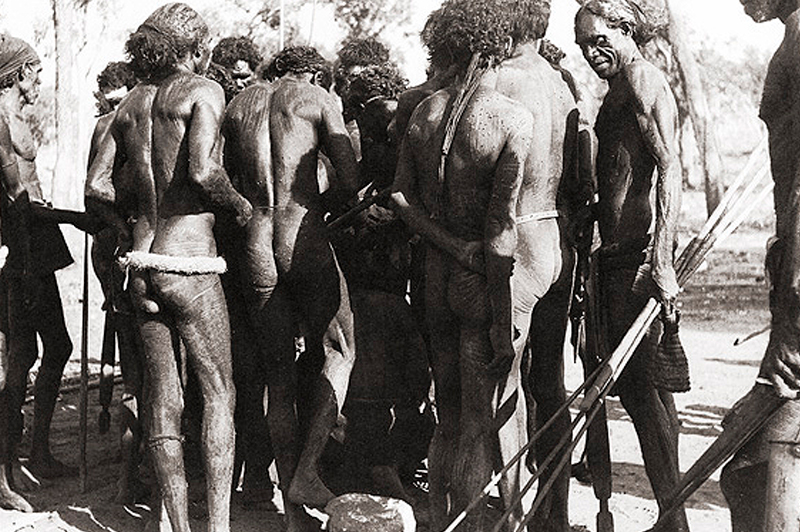

The relevant permits were obtained. The Frobenius Institute expedition arrived in Broome by circuitous route early the next year. Under the leadership of a young specialist in Aboriginal and Oceanic societies named Helmut Petri the team then travelled from Walcott Inlet deep inland through the territories of the Worora and the Ngarinyin.

Their discoveries were spectacular; their timing was poor.

They had only just returned to Germany after their lengthy field investigations when war broke out. The frayed ties of academic co-operation between Germany and the English-speaking world were promptly severed.

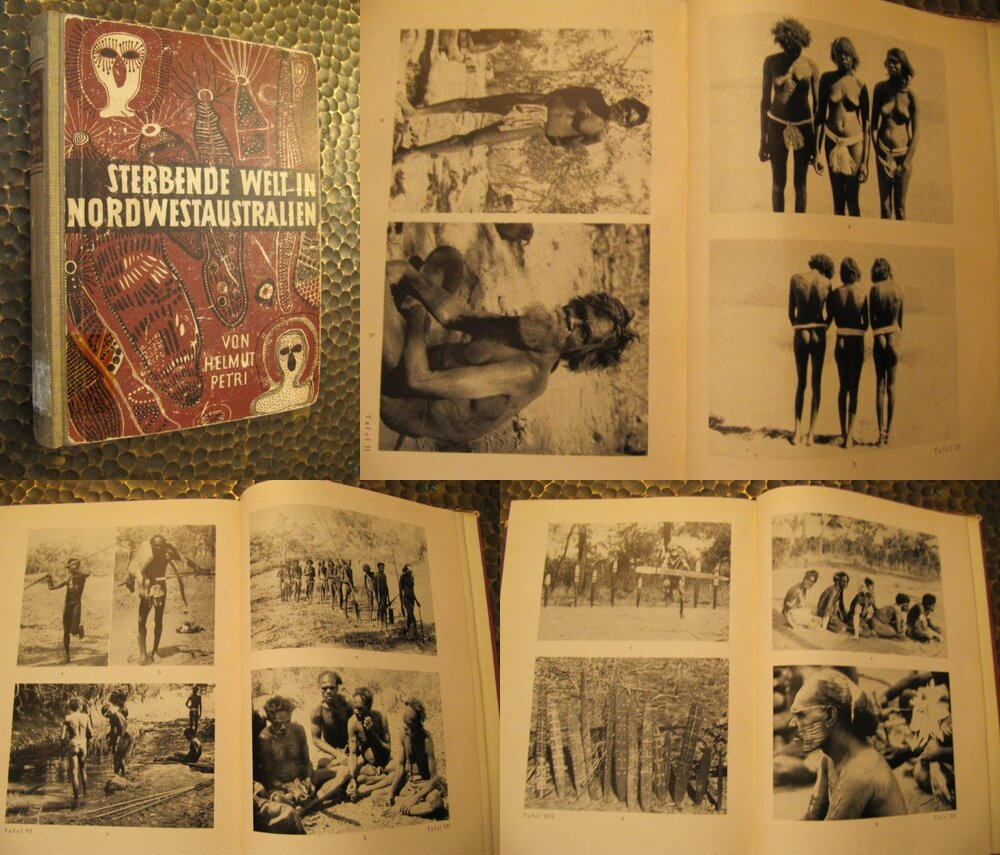

Much of the material Petri and his team had gathered up was destroyed in the allied bombing raids that levelled Frankfurt-am-Main to the ground. It was only nine years after the end of World War II that Petri was able at last to publish an abbreviated account of his findings.

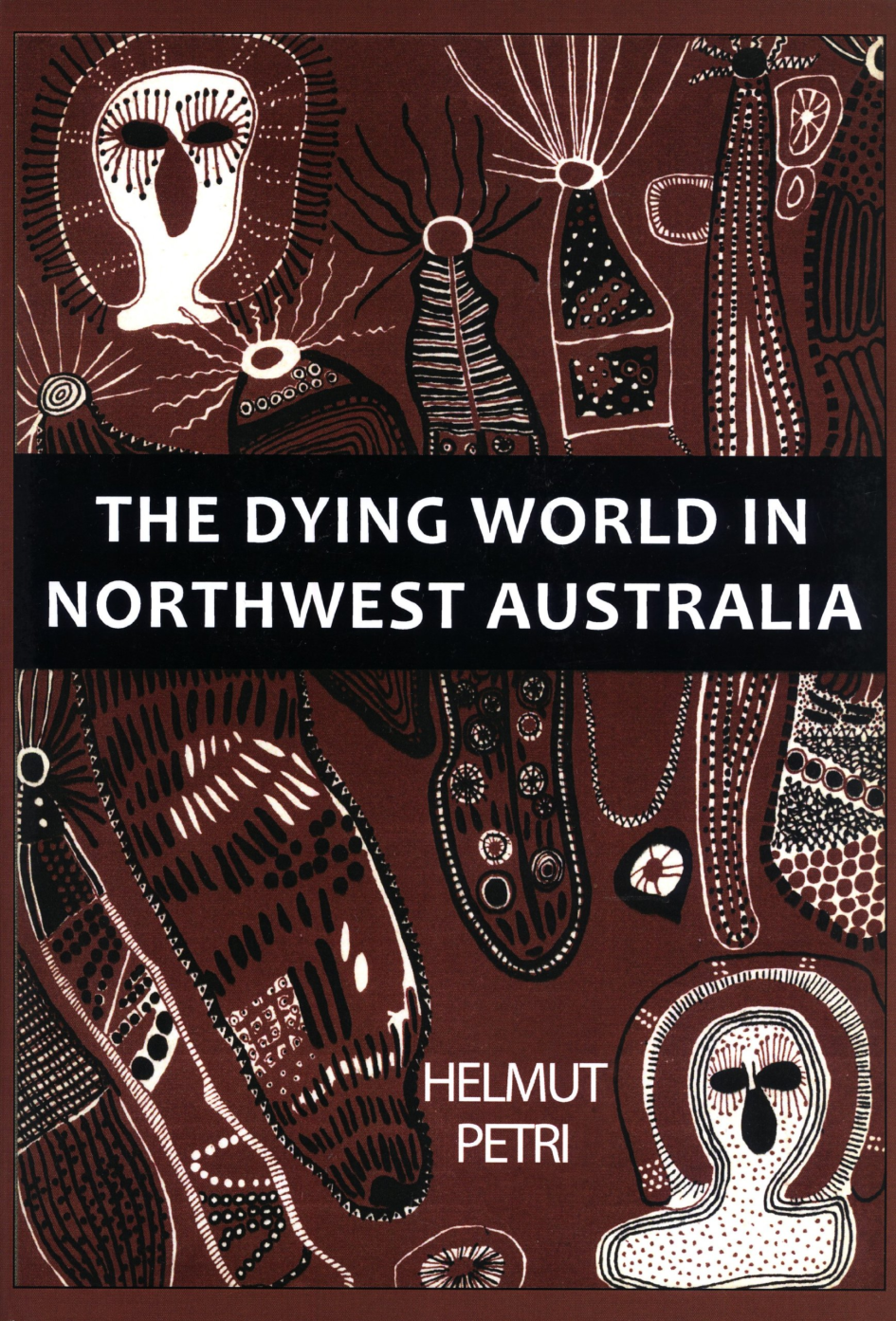

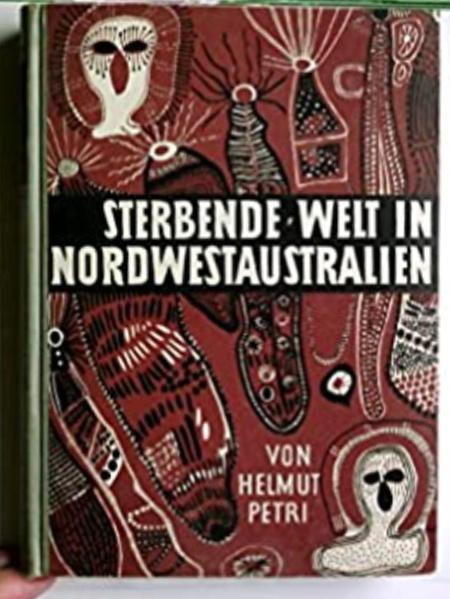

“Sterbende Welt in Nordwest Australien” is a production of great beauty, shot through with overtones of mourning and grief. Petri regarded it as no more than a damaged torso, a fragment of the book he planned to write – but that fragmentary quality gives the work much of its force.

Although it is ostensibly concerned purely with ethnographic description of remote tribes and their social adaptations, it is in fact a study of a culture under stress and in collapse, and when I first came across it and made my way though its pages I at once felt it held the key to any truthful understanding of north Australia’s first civilizations and their fate.

“Sterbende Welt” is written in a smooth and understated German. It was translated at the insistence of the rock art scholar Grahame Walsh, who entrusted the task to a notable specialist, Ian Campbell, of the University of New England. That translation offers to an anglophone readership the unsparing details of what Petri learned and saw: things so disquieting they drew him back to the Kimberley and the desert fringe repeatedly, and made him into a kind of nomad, or pilgrim, constantly haunting the mission settlement of Lagrange on the north-west coastline, where the large Aboriginal community of Bidyadanga stands today.

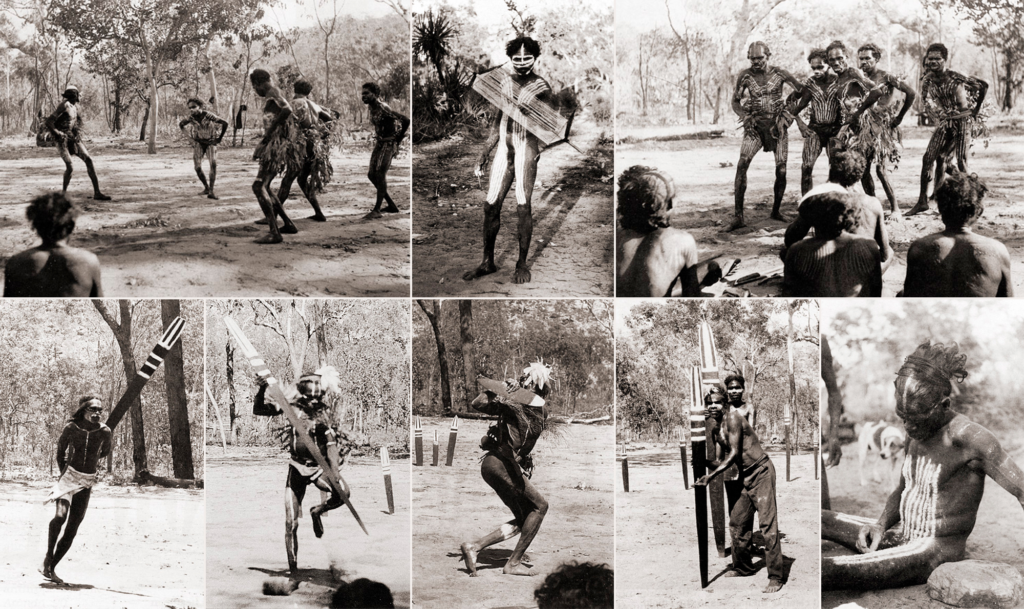

Petri paints a picture of a world in dissolution, but he also records the startling, furious energies of creation at work in the societies he came to know. The established religions of the north-west were failing, new cults of extraordinary vigour were sweeping through.

They were imbued with danger, they involved acts of profanation and the speaking of secret words, they had a messianic, despairing edge.

Chief among them was the Kurangara, which Petri, like his colleague on the Frobenius expedition Andreas Lommel, understood as a response to the pressures of invasion and colonial subjection.

The Kurangara resembles a range of other such cults recorded during the same period across frontier Australia, but the detail with which it is captured in this German text allows us to see into its heart, and see there something critical about the thought-world of Aboriginal north and central Australia – an element that was present in the middle years of the 20th Century and persists in disguised fashion to this day.

When Petri began his work, the cult was at its peak and was spreading fast across the Kimberley. It dominated Dampierland and had a firm foothold in the country of the Ngarinyin, the Worora and the Unambal.

It was on the march towards the east. But its origins were in the Centre, in the deserts, in some imagined pure domain where Aboriginal societies still possessed strength and magic force. It had been brought north by the Djanba, spirits of the inland, creatures of aridity, fearful beings. They lived in the dry heart of the continent. It was there, in distant country, that they kept their subterranean camps. They had emerged from the red soil at the start of time.

They were shape-shifters, they knew everything and could do anything, they could travel on the waves of thought, and see for endless distances.

The Djanba were fair-skinned, and had long beards, but Kimberley people rarely saw them, for they travelled at speed, leaving no footprints where they walked, not pausing even for a moment’s rest. They were most active on moonless nights, or in the haze-tormented midday heat, when their bodies cast no shadows; and they were thirsty – inordinately thirsty – both for water, and for the blood of humankind. Dances, songs, cult objects and potent rituals were associated with these beings, but no one except the adepts of the cult could understand their mysterious desert language.

There are many features of this ritual complex and its associated sexual practices which Petri describes and which I will pass over, but certain other tell-tale aspects of the Kurangara, provided by Lommel, point to the well-springs of the cult.

Thus it is very striking that the Djanba spirits are described as having horns on their heads just like a bull’s horns. When they come into the Kimberley they live in houses of corrugated iron like station homesteads. To hunt they use sticks like rifles. They point them – then thunder sounds, lightning strikes, the earth trembles and everywhere many kangaroos fall dead to the ground. There is an “end of the world” atmosphere about these anecdotes that must be put down to Christian influence, but the essence of the cult’s origins are plain.

In the Kurangara the new experiences flowing from the encounter with white civilization have been transmuted, given artistic form.

Such were the symptoms of crisis and dislocation Petri found awaiting him – signs. Signs that spoke of revolution in the realm of belief and God.

It is clear that there is a two-fold movement under way: resistance, and co-option. Defiance, and surrender to the seductive play of influence. The German ethnographers, who were watching this tableau unfold before them even as a deathly cult swept through their own world, knew very well what they were witnessing: the end of an epoch; a time of dreadful instability; the first seeds of a new accommodation being sown.

They realised that the sacred never vanishes. It flows, wave-like, through men’s lives, moving smoothly from form to form.

Lommel saw these shifts through the prism of psychology. He felt the Aboriginal societies of the Kimberley somehow needed a living, strong magical atmosphere. A magic cult gave people a spiritual focal point lying outside themselves.

Without such an atmosphere a total disintegration, a great spiritual disorder and disorientation must occur.

Petri, for his part, grasped the essence of the phenomenon almost at an instinctual level. Perhaps it needed an outsider’s eyes to diagnose the process.

“It is a well known fact,” he wrote, “that European colonization upset the spiritual equilibrium of the Australian Aborigines.” The religious compact at the heart of life had failed. The relationship between the generations had been overthrown.

The young, seeing the white world in all its destructive potency, had lost faith in their own traditions, but the workings of western civilization were impenetrable to them. They found in the spirits of the new cults the inner support that old beliefs could no longer give.

How to miss the lurking pattern? Millenarian cults and religious uprisings share a straightforward grammar. The old law fails. It is overturned, a new law is preached, and that law is founded on the shock of sudden revelations. It will tend to borrow elements from the oppressive, threatening new master power abroad in the world. It adapts, it assimilates, it resists – it proclaims year zero, and awaits a dawn.

This pattern, when it appears in Australian frontier history, as it has often, is rarely seen for what it is, for that frontier is viewed and understood through mainstream eyes – and our picture of past events in both the deserts and the tropical and savannah country is a picture freighted down by sentiment and perspective bias.

Few frontier dwellers and specialists in the area really understand that the frontier has another side. Few historians of the inland and the encounters that have occurred over the past two centuries against that backdrop realize that men and women in traditional societies still half-expect non-indigenous Australians to leave their country at some point, when certain ritual cycles are complete.

For outsiders in the bush do not, on the whole, think magically, or see the ceremonial logic of that world and the compelling force it exerts upon those plunged within it.

The ideas western observers apply to the Aboriginal realm come, rather, from social science and cultural frameworks. They are the ideas of the Bohemian, the intellectual, the aid worker or the enlightened functionary, and they bring confusion in their wake.

Strangely, the first generations of incomers in the remote world were much better equipped – the missionaries, with their belief in divine providence, were on the same wavelength as the tribal groups they moved amongst and were at pains to convert, and the relative harmony and happiness of the missionary era may well be largely due to this confluence of understandings and views of life.

Two generations ago that system of frontier management fell into abeyance. Another order was imposed, an administrative order, elaborate, with constantly shifting priorities.

It was at this very point that one of the most widely studied and most elusive interactions between traditionally-accented Aboriginal society and mainstream Australia unfolded – the western desert art movement, which was born in Papunya settlement exactly 40 years ago, and it is to this landscape, this remote community grandly set in the folds of the purple Ulumbara range that I transport you now.