Reporters Without Borders

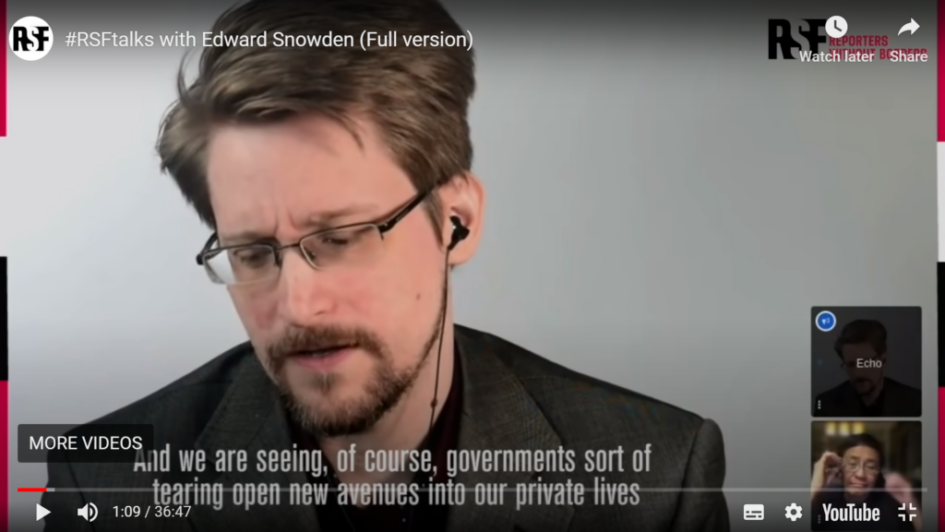

This is an interview with infamous whistleblower Edward Snowden, conducted on behalf of Reporters Without Borders by Filipino journalist Maria Ressa to mark World Press Freedom Day.

Maria Ressa: it is a decisive decade for journalism.

Edward Snowden: Everybody who looks around right now, they can see, they can feel what’s in the air. Everything is changing rapidly. We are seeing new powers being claimed. We are seeing new powers being abused.

And we are seeing governments tearing open new avenues into our private lives under the justification of emergency measures.

You know, they always say these are temporary, it is for this reason and that reason… But there is nothing more permanent than a temporary measure.

The system is now failing.

Our efforts to correct it are being stymied in large part because the first into fixing a problem is understanding it and humanity’s traditional method for rapidly digesting and sharing information, journalism, is under attack. I think that is an intentional strategy. I don’t think it is a coincidence, I don’t think it is a mistake, I don’t think it it an unintentional overreach.

I regret to say that the intensity of these attacks are increasing at the very moment when we are approaching what I consider the “apex” of crisis in places where reliable information is most difficult to obtain such as China. We witness new efforts to expel journalists and keep them out of the country and bar their work. We have seen pressure on their colleagues. We have seen influence campaigns against their outlets and institutions.

And it is not just in China and places like it. In Brazil, federal prosecutors sought to imprison a journalist for exposing corruption in the Justice Ministry. In the UK, the whole society is standing by the most basic tenants of international law and human rights are being disregarded in order to extradite Julian Assange, the publisher of Wikileaks for 17 counts of espionage, which is according to the charging documents how we have come to describe the act of publishing true and correct information.

And this process is accelerating. In Russia, we see this dynamic happening at the same time the government, the State, is climbing up the ladder of laws against so called “false information and the spreading of rumors”.

And we get to see this in many countries around the world, which tragically brings us to the United States where no less than the President himself leads the same war in the same words from behind the podium that even his supporters admit is the origin of a great deal of the very fake news that he so often decries.

The sources of true information – the sources of journalism – are under the kind of threat that we have really never seen before.

It has always been difficult to be a journalist’s source, just as when you are breaking a truly impact for a meaningful story as a journalist, we know it has personal and professional risks, sometimes risks to life unfortunately.

We are seeing for the first time retaliation being taken in a systematic way against oversight officials, against watchdogs, against inspectors general and we see this happening in places like the United States. These are just the smallest examples of a very long list of the threats that we see facing the work of the free press today.

And yet, the skeptical press is never more critical than in times of crisis.

What we are going to find very rapidly is that we are not going to have access to information precisely in the moments when we need it the most, and as it is society and as the ultimate stewards of the system of our world we must be willing to protect those who do the work of warning and preparing us to weather this continuing series of shocks and, at times, assaults that are fundamentally, the progress of history.

The work of journalism is imperfect, right? There are legitimate criticisms that can be made, about this story, about this outlet, about this reporting. And yet, journalism is necessary, corrections can be made, improvements are a part of the process of journalism. Correcting the record is a thing but if we cannot or do not protect journalism the system of our world will fail and the cost will be measured in freedoms.

MR: One of the things that your work – the whistle-blowing that you did – is on the kind of mass-surveillance that was happening was being done by governments. In the last few years of the reports of Reporters Without Borders – in their Press Freedom Index – one of the biggest changes that they put in was disinformation. Disinformation coming in from the new gatekeepers because it is clear from your actions that you respected journalism, you went to journalists to go through the information that you had but now journalists are no longer the gatekeepers; technology platforms are, social media platforms are and the role of the gatekeeper has changed. That has brought in this disinformation. What role do you see technology and social media platforms playing now?

ES: This is a point of tremendous controversy because some people like to see journalists and institutions of journalism as the gatekeeper’s right but I think that there is more complexity to it than that. When we talk about misinformation and social media, technology platforms, what they have done is democratize the means of publication, the means of transmission – now everybody can put anything out there.

What journalism does, I think, best (organized journalism, rather) is to be able to commit resources (human, financial, everything) into research studying the facts. Ultimately, looking at conflicting claims and trying to determine what is true – or more likely to be true based on the evidence that is available to us – I mean, they are making hard calls when there are groups a-cross purposes, for example, the government says that the public should not know that there is a global system of mass-surveillance that it is violating all of their rights because they would go “Look, it may give us useful means of investigation”, the more secret it is, the more effective it is.

But on the other side, there is a violation of every individual’s right and of our collective rights. And who should make the call, as to whether the public should or should not know this?

It could have been me, it could have been anyone who knew this information, I mean, I could have just put it up in a tweet but I felt that, you know, I had strong political opinions, I gathered the evidence… but I think journalism and journalists are intentionally designed – at least in the US system with our first amendment protections – they are entrusted to challenge the government in an institutional way – that is why we called them the Fourth State.

The government traditionally has a monopoly on many facts because they use classification powers and things like that to say “we might be doing it but we won’t tell you one way or another and you can’t do anything about it”. So what do we do? We investigate and then we gather the facts, and then somebody somewhere has look and this and go “Ok, it is true, what parts of it can be published without creating extraordinary risks, right?”.

People are putting things out there, there can be true and useful information that no one else is willing to put out, maybe there are commercial interests – in the United States there is a lot of commercial influence in journalism and that is the same in many other countries – somebody puts it out and it is true.

Well, now we have a new problem, we have access to more information than we have ever had before but as you say, how to we know what of this information is true, is correct, is reliable. Who tests that? And that is, I think, what we are really struggling with.

The social media companies, the technology companies are increasingly trying to play a role there, they are going “Well, you know, we will hire people” and they will say “This is reliable or this is fake news…”

In some ways, maybe, that can be useful. But I think that is actually the wrong approach because these institutions already have so much power over our lives.

They have so much information about us, about our interests, about our connections, about our reading habits and if we start putting them in the position where they go “well, this protest can’t be promoted or “this speech is too extreme for the platform”, there are many cases in where that could be very good and beneficial for society but I can imagine a whole lot more, in a whole lot of countries where that actually does damage to democracy and it is the progress of human rights. So it is very much a difficult question.

MR: The hard part is that you exposed mass-surveillance of a powerful nation, of the United States. That now is not just in the hands of governments – private companies have this capacity as well. Given the coronavirus … we are now giving even more power to governments – contact tracing. How can we solve the problem of the virus without losing more of our freedoms?

ES: When you look at the stories of 2013 that had the most impact that created the greatest scandal, it wasn’t what the government was doing alone, it was that the government was going to the corporations, they were going to the major telecommunications providers in the United States and they were saying “we want the phone records of everyone in the United States: men, women, child, regardless of whether they are suspected of crime and we want you to provide them to us every-single-day rolling-basis”.

They went to the major internet-service companies: they went to Google, they went to Apple, they went to Facebook, they went to Yahoo and many more and they went “Look, we have got a process in secret courts where we are going to rubber-stamp warrants” and this is a court that was asked about thirty thousand times and over thirty-three years to authorize surveillance for the government and out of those thirty thousand times roughly, they heard from this court “no” only eleven times in thirty-three years. This is very much a rubber stamp and yet that was good enough for many of these companies.

These companies then began secretly collaborating with the government, where the government would sort of slip them a rubber-stamp to a piece of paper that then says “this email address, this user, you know, this person here, we want everything that is on your servers” and they would make a perfect copy from their servers and they would pass it to the government and no one would be the wiser.

The person who had been subject to the surveillance wouldn’t even be notified, they wouldn’t get a chance to contest it in court. But the core here is that as much as the government was doing, as much as this intrusive capability was being constructed and carried out, we were creating for the first time perfect records of private lives at a scale that had never been done before. It was leading to something greater, which is to what we see today.

This is an edited transcript.

3 Pingbacks