By Alexander Schmidt-Lebuhn, Research Scientist and Ben Gooden, Plant Ecologist, CSIRO.

We accidentally found a whole new genus of Australian daisies. You’ve probably seen them on your bushwalks.

When it comes to new botanical discoveries, one might imagine it’s done by trudging around a remote tropical rainforest. Certainly, that does still happen. But sometimes seemingly familiar plants close to home hold unexpected surprises.

We recently discovered a new genus of Australian daisies, which we’ve named Scapisenecio. And we did so on the computer screen, during what was meant to be a routine analysis to test a biocontrol agent against a noxious weed originally from South Africa.

Read more: Tree ferns are older than dinosaurs. And that’s not even the most interesting thing about them

The term “genus” refers to groups of different, though closely related, species of flora and fauna. For example, there are more than 100 species of roses under the Rosa genus, and brushtail possums are members of the Trichosurus genus.

This accidental discovery shows how much is still to be learned about the natural history of Australia. Scapisenecio is a new genus, but thousands of visitors to the Australian Alps see one of its species flowering each summer. If this species was still misunderstood, surely similar surprises are still out there waiting for us.

How it began

It all started with a biocontrol researcher asking a plant systematist, who looks at the evolutionary history of plants, to help figure out the closest Australian native relatives of the weed, Cape ivy (Delairea odorata).

Weeds like Cape ivy cause major damage to agriculture in Australia, displace native vegetation and require extensive management. Biological control (biocontrol) is one way to reduce their impact. This means taking advantage of insects or fungi that attack a weed, generally after introducing them from the weed’s home range.

A well-known Australian example is the introduction of the Cactoblastis moth in 1926 to control prickly pear in Queensland and New South Wales. Even today it continues to keep that weed in check.

Read more: Explainer: how ‘biocontrol’ fights invasive species

To minimise the risk of selecting a biocontrol agent that will damage native flora, ornamental plants or crops, it’s tested carefully against a list of species of varying degrees of relatedness to the target weed.

Authorities will approve the release of a biocontrol agent only if scientists can show it’s highly specific to the weed. Assembling a list of species to test therefore requires us to understand the evolutionary relationships of the target weed to other plant species.

If such relationships are poorly understood, we might fail to test groups of species that are closely related to the target.

Missing data

Our target weed Cape ivy is a climbing daisy that has become invasive in temperate forests and coastal woodlands throughout south-eastern Australia. One of us, Ben Gooden, is researching the potential use of Digitivalva delaireae — a stem-boring moth — for its biocontrol.

We tried to design a test list, but could not find up-to-date information on Cape ivy’s relatives. We already knew it is related to the large groundsel genus Senecio, but we didn’t know how closely. And no genetic data existed for many Australian native species of Senecio.

So, we set out to solve this problem together.

First, we assembled already-published DNA sequences for as many Senecio species and relatives as we could find, and then generated sequences for an additional 32 native Australian species.

We then united all these genetic data into a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis. “Phylogenetics” infers the evolutionary relatedness of organisms to each other.

Hidden in the evolutionary tree

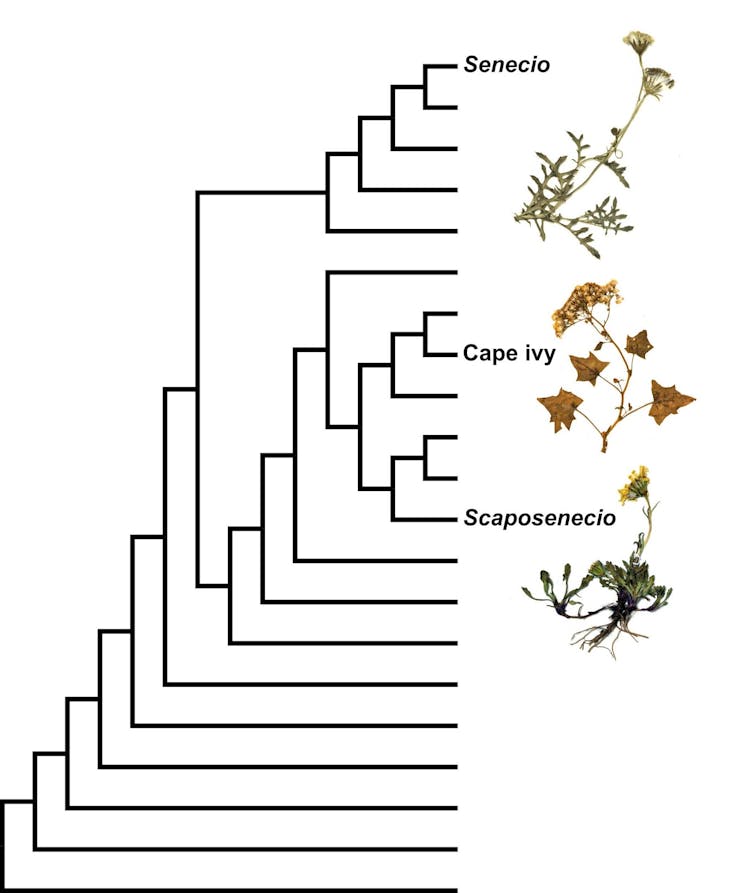

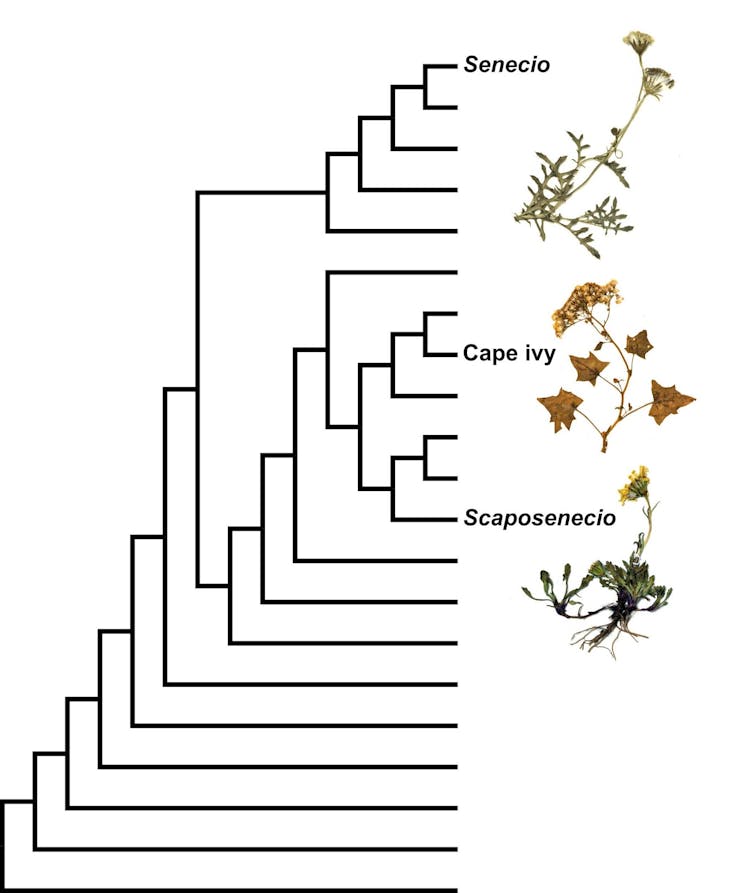

The resulting “evolutionary tree” showed many of the native Senecio species where we expected them to be. More importantly, however, it showed us that Cape ivy is actually quite distantly related to Senecio.

To our surprise, the analysis also placed several Australian species traditionally belonging to the Senecio genus far outside of it, indicating they didn’t belong to Senecio at all and needed to be renamed.

The most interesting group of not-actually-Senecio are five species with leaf rosettes and one (or rarely, a few) flowerheads carried on distinctive stalks.

They’re all restricted to alpine or subalpine areas of south-eastern Australia, and all except one are found only in Tasmania. They turned out to be so unrelated, and so distinct from any other named plant genera, that they have to be recognised as a genus in its own right.

Introducing Scapisenecio

We have now named this new genus as Scapisenecio, after the long flower stalks (scapes) characterising the plants.

The most widespread and common species is Scaposenecio pectinatus, commonly known as the alpine groundsel, which is a familiar sight to hikers and bushwalkers in the Australian mainland alps and the central highlands of Tasmania.

Apart from the excitement of finding a previously undescribed, distinctive genus, these results were also directly relevant to the original purpose of our work: informing a plant list to test possible biocontrol agents.

The traditional misclassification of these species would have misled us about their true relationships. Our new genetic data now allow us to test biocontrol agents on an appropriate sample of species, to minimise risks to our native flora.

It is not often we find that a new, unexpected lineage of plants has existed all along, right in front of us.

Alexander Schmidt-Lebuhn, Research Scientist, CSIRO and Ben Gooden, Plant ecologist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Murray Fagg/Australian Plant Image Index.

Weeds like Cape ivy cause major damage to agriculture in Australia, displace native vegetation and require extensive management. Biological control (biocontrol) is one way to reduce their impact. This means taking advantage of insects or fungi that attack a weed, generally after introducing them from the weed’s home range.

A well-known Australian example is the introduction of the Cactoblastis moth in 1926 to control prickly pear in Queensland and New South Wales. Even today it continues to keep that weed in check.

Read more:

Explainer: how ‘biocontrol’ fights invasive species

To minimise the risk of selecting a biocontrol agent that will damage native flora, ornamental plants or crops, it’s tested carefully against a list of species of varying degrees of relatedness to the target weed.

Authorities will approve the release of a biocontrol agent only if scientists can show it’s highly specific to the weed. Assembling a list of species to test therefore requires us to understand the evolutionary relationships of the target weed to other plant species.

If such relationships are poorly understood, we might fail to test groups of species that are closely related to the target.

Missing data

Our target weed Cape ivy is a climbing daisy that has become invasive in temperate forests and coastal woodlands throughout south-eastern Australia. One of us, Ben Gooden, is researching the potential use of Digitivalva delaireae — a stem-boring moth — for its biocontrol.

We tried to design a test list, but could not find up-to-date information on Cape ivy’s relatives. We already knew it is related to the large groundsel genus Senecio, but we didn’t know how closely. And no genetic data existed for many Australian native species of Senecio.

So, we set out to solve this problem together. First, we assembled already-published DNA sequences for as many Senecio species and relatives as we could find, and then generated sequences for an additional 32 native Australian species.

We then united all these genetic data into a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis. “Phylogenetics” infers the evolutionary relatedness of organisms to each other.

Hidden in the Evolutionary Tree

The resulting “evolutionary tree” showed many of the native Senecio species where we expected them to be. More importantly, however, it showed us that Cape ivy is actually quite distantly related to Senecio.

To our surprise, the analysis also placed several Australian species traditionally belonging to the Senecio genus far outside of it, indicating they didn’t belong to Senecio at all and needed to be renamed.

Simplified phylogenetic tree of the daisy tribe Senecioneae showing the evolutionary distance between Senecio, Cape ivy, and the new genus. Unlabelled branches indicate other lineages of the same tribe.

Alexander Schmidt-Lebuhn, Author provided

The most interesting group of not-actually-Senecio are five species with leaf rosettes and one (or rarely, a few) flowerheads carried on distinctive stalks. They’re all restricted to alpine or subalpine areas of south-eastern Australia, and all except one are found only in Tasmania. They turned out to be so unrelated, and so distinct from any other named plant genera, that they have to be recognised as a genus in its own right.

Introducing Scapisenecio

We have now named this new genus as Scapisenecio, after the long flower stalks (scapes) characterising the plants.

The most widespread and common species is Scaposenecio pectinatus, commonly known as the alpine groundsel, which is a familiar sight to hikers and bushwalkers in the Australian mainland alps and the central highlands of Tasmania.

Species belonging to this genus are a common sight to alpine hikers. Alexander Schmidt-Lebuhn, Author provided.

Apart from the excitement of finding a previously undescribed, distinctive genus, these results were also directly relevant to the original purpose of our work: informing a plant list to test possible biocontrol agents.

The traditional misclassification of these species would have misled us about their true relationships. Our new genetic data now allow us to test biocontrol agents on an appropriate sample of species, to minimise risks to our native flora.

It is not often we find that a new, unexpected lineage of plants has existed all along, right in front of us.

Read more:

‘Majestic, stunning, intriguing and bizarre’: New Guinea has 13,634 species of plants, and these are some of our favourites

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.