By Sheila Fitzpatrick, Australian Catholic University

One interpretation of the name “Ukraine” is borderland. This needs to be taken seriously.

Borderlands are all about diversity and competing understandings of community and nation. They are always mixtures of people with different languages, religions and customs. Some will think of themselves as kin to the people on one side of the border; some look to the other side.

In Ukraine, the West (Europe) is one side of the border, the East (Russia) the other.

Among those in the eastern parts of Ukraine (Donetsk, Luhansk) who tend to look East are descendants of the Russian peasants, like the parents of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who around the turn of the 20th century came to work in the Donbass mines.

In borderlands like Ukraine, there are generally competing origin stories.

Ukrainians tell a story of the origins of the Ukrainian nation going back to 11th century Kyiv, surviving centuries of oppression by Russia and Poland, and, finally, emerging out of the wreckage of the Soviet Union as a sovereign Ukrainian state in 1991.

For the Russians, the various western and southern provinces now called “Ukraine” were populated by Slavic border people (Ukrainians) who were essentially Russian. They considered this land as a part of the Russian Empire for centuries.

The Australian press has been treating the Ukrainian origin story as “truth” and the Russian one as “lies,” but things are never that simple. Like all origin stories, both are a mixture of historical fact and political imagination.

A modern country

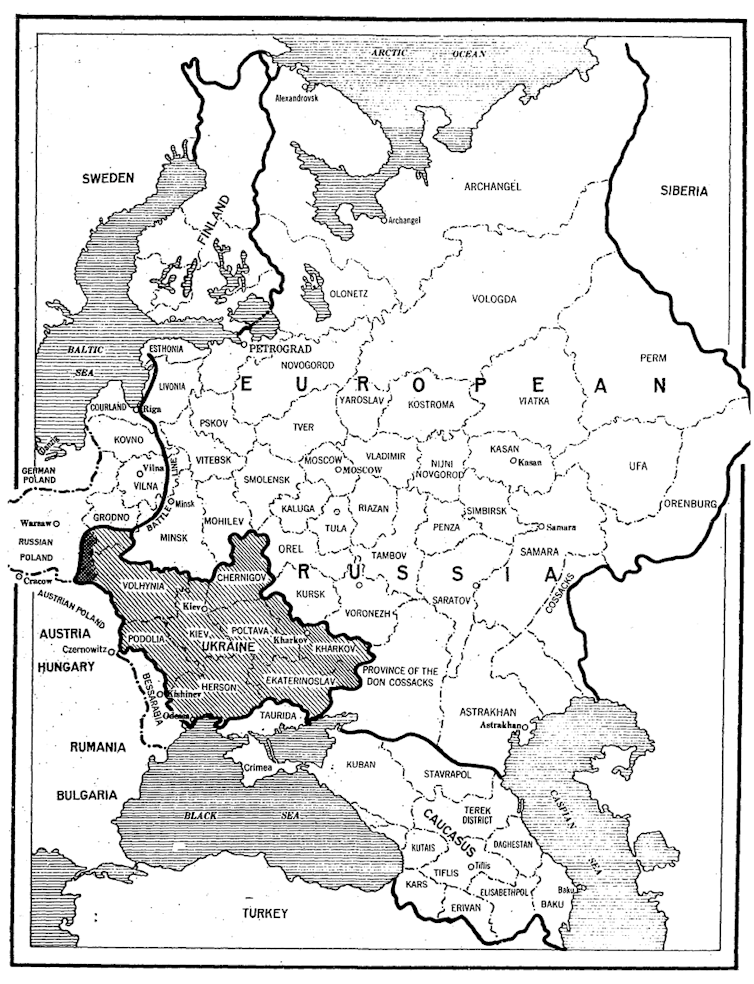

Ukraine’s modern history as an independent state amounted to a few tumultuous years of a shaky Ukrainian People’s Republic between the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the consolidation of the Soviet Union in 1920.

Ironically, its incorporation into the Soviet Union as one of its original constituent republics was an important milestone on the path to national sovereignty.

This incorporation established territorial boundaries, recognised Ukrainians as the republic’s titular nationality, and, for 70 years, offered the republic’s communist leaders a substantial degree of autonomy (increasing over time) in the internal government of their territory.

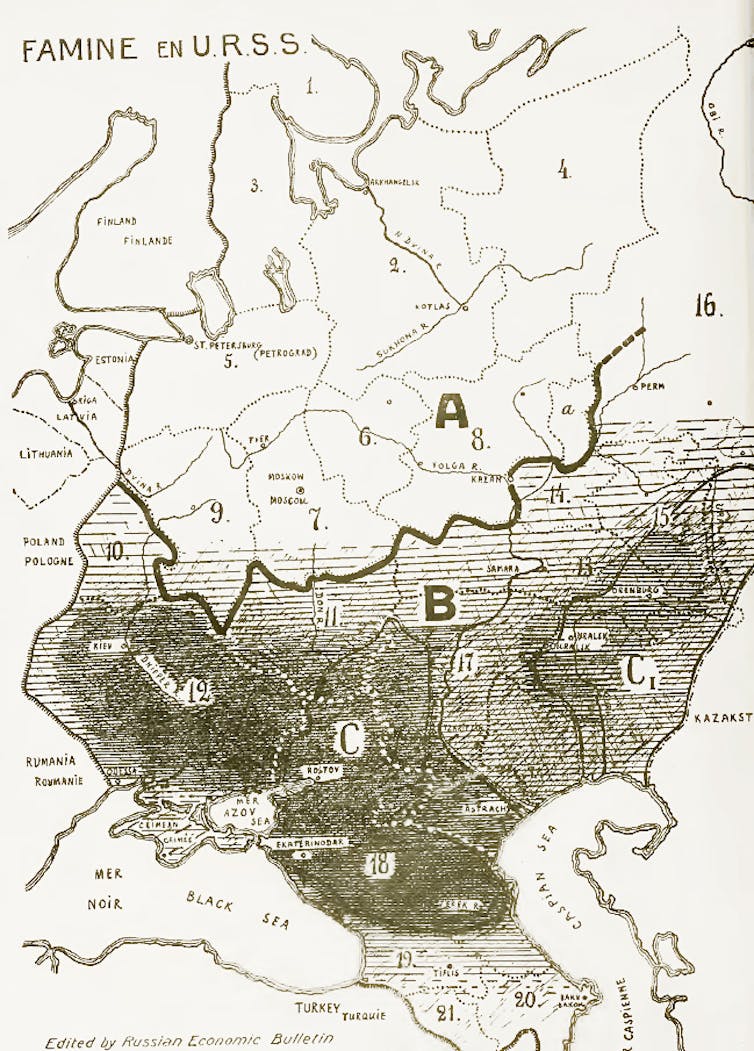

Post-Soviet Ukraine has built a national identity around the memory of Holodomor, the famine of the early 1930s which is seen by the current Ukraine state and some historians as a punishment Stalin intentionally visited upon Ukrainians.

There were undoubtedly black chapters in the history of Soviet Ukraine, as of the Soviet Union in general.

From the mid 1950s, the top official in Ukraine was always a Ukrainian, and Ukraine had its men in the party Politburo (the top Soviet policy-making body) and substantial influence in Soviet national affairs.

Nationalist and, ultimately, separatist feeling increased in Ukraine during Gorbachev’s perestroika (1985-91), but less than in the Baltic states or even the Caucasus.

As late as March 1991, 70% of the Ukrainian population voted to remain in the Union.

But by December the great majority of Ukrainians voted for independent sovereignty.

Kith and kin

In recent weeks, the depth and sincerity of the commitment to Western democracy, the repudiation of the Communist past and rejection of the Russian connection has been impressively demonstrated by the Ukrainian government and people.

Russians whose memories go back 30 or 40 years might see the Ukrainian situation differently.

This is not just a matter of one deluded autocrat (President Vladimir Putin) leading Russia into a deranged quest for aggrandisement. This is a story of the attitudes and assumptions of the majority of the Russian population, which up to now has supported Putin and (at least pre-invasion), his Ukrainian policy.

The appalling and tragic decision to invade Ukraine may have been Putin’s alone. Pre-invasion Russian opinion polls are an unreliable guide to the future. It is not clear if the younger post-Soviet generation – in particular, young men liable for military conscription – see Ukraine and its current Western orientation in the same way as their elders.

Putin’s past wars and acts of aggression on the international scene (Chechnya, Crimea) raised his popularity at home, but they were successful wars. So far, Russia’s Ukrainian adventure is not looking like a success.

In the case of Crimea (which, as all Russians know, was transferred from Russia to Ukraine in 1954 on a whim of Khrushchev), this agression was essentially bloodless.

Chechnya was bloody, but the victims were not Slavs.

It remains to be seen how the Russian Army and Russians back home will feel about the killing of Ukrainians: Slavic kith and kin.

Sheila Fitzpatrick, Professor of History at the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.