Sally Breen, Griffith University.

In this series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

I first read Eve Babitz at the tail end of the 20th century, holed up in the rumpus room of my parent’s house in north suburban Brisbane in exile from my bad behaviour on the Gold Coast.

I’d found Eve by accident, trawling through all the literature I could find written about Los Angeles. I was doing a PhD, trying to write a book and drawing connections between her dream city and my own California in miniature, the GC.

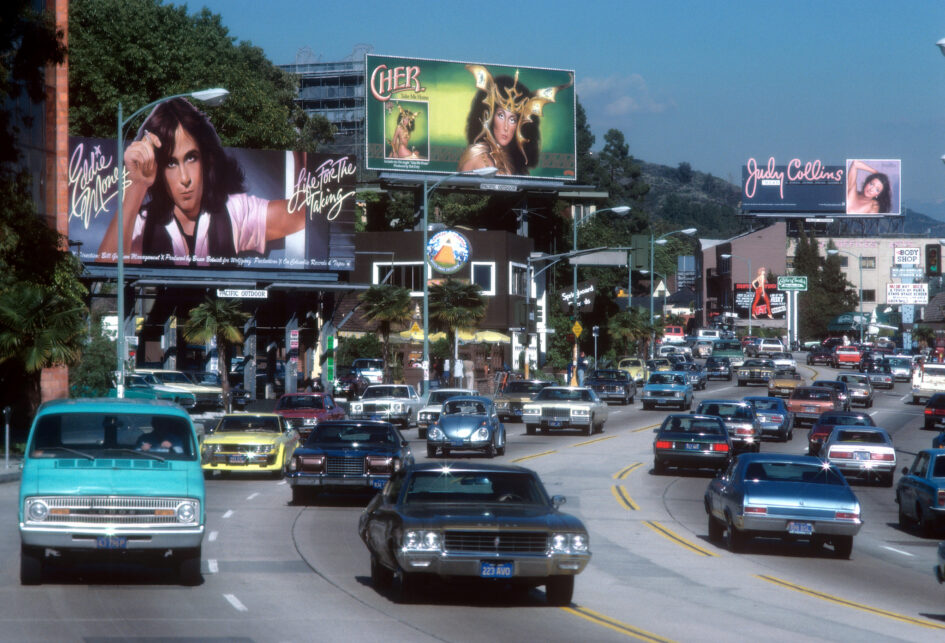

As the dogs barked and the council trucks emptied out the wheelie bins I’d stare forlornly at the dead end of cul-de-sac, longing for sea salt and palm trees, faithfully transcribing the words of male writers, English and European men on unhappy sojourns in 1940s Hollywood: Bertolt Brecht, Aldous Huxley and Evelyn Waugh and the forerunners of LA noir, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammet and Nathaniel West.

Men holed up in their bungalows in the Hills or the orange groves telling the world hell was a movie set full of femme fatales who drove you mad until they were avenged. The work overflowing with heady (mostly repressed) sexual desire resulting in a twisted wish for the annihilation of their heroines and for LA’s apocalypse.

Decades later, Eve was having none of it.

When I managed to track down copies of her books (all out print at the time) she articulated in a welcome sonic blast what I’d been thinking – it was possible for the femme fatale to leap off the leopard skin rug and hijack the narrative. Wrote Eve:

I would read books like The Loved One and the Day of the Locust or Ape and Essence by Aldous Huxley. The point of these books as far as I, a bleached blond teenager growing up in Hollywood, was concerned was that though the authors thought they were so smart – being from England or the East Coast and so well educated and everything – they were suckers for trashy cute girls who looked like goddesses and just wanted to have fun. These men could say what they liked about how stupid and shabby and ridiculous LA was, but the minute they stepped off the train, they were lost. All their belief in the morals and tenets of Western civilisation was just a handful of dust.

I was hooked. And fell in love with Jacaranda, the star of Sex and Rage as she swans around Los Angeles caught between finding and re-making herself, a young woman whose default response to any probing question is, “Who me?” allowing her to slide away from commitment – to anything.

Sun-kissed, lurid avant-garde

Where Evelyn Waugh might have described Jacaranda’s heart as “a small inexpensive organ of local manufacture”, Eve revels in her heroine’s contradictions and sets about dismantling the arbitrary lines between high and low culture in a voice and attitude entirely her own.

Jacaranda is an ingenue, a hustler, a hedonist and a hanger on, in a certain light, but she is also an artist, a writer, a surfer and a bohemian infused with Eve’s special brand of sun-kissed, lurid avant-garde.

The Bamboo Café was designed by artists and looked like an LA-Flying Down to Rio banana leaf ode. Its walls were pink and its tablecloths were chartreuse like the floor (which was marbled in pink). Artificial flamingos stood in the front windows among chartreuse banana leaves. And flamingos in chartreuse were silhouetted against the pink wallpaper …

Shelby, the day he came into the Bamboo Café, was still the same, the L.A. artist, tall and slender, the master of balance surfer he had always been, and he still had that edge of elegant old fashioned good manners. He was wearing faded old jeans and a bleached out Hawaiian shirt, and all the women in the restaurant stopped, their glasses half-way to their lips, their sentences unfinished – Shelby was more wicked and coyote-looking than ever, more silent and strange, more siren song about the islands … she went outside with Shelby.

Sex and Rage, first published in 1979, is a novel about playing the game and surviving long enough to become something in a masculine world and I was gunning for Jacaranda, dancing a fine line on a seductive flotilla of men – lovers, artists, movie executives, restaurant owners, actors and rock stars who all wanted to play with her until they wanted to take her down.

Her nemesis, Max, “a figure in the landscape who began moving into the festivities as soon as he knew someone was looking” an international man of mystery in charge of what Babitz describes as “the barge” a rarefied world of jet setters she’s allowed onto for a time until the fall out nearly destroys her. Her paranoia and insecurity offset by buckets of alcohol; the medicine Jacaranda needs to give good play.

Jacaranda thought of the ‘dear friends’ living on a drifting, opulent barge where peacock fans stroked the warm river air and time moved differently from the time of every place else. Everything was better on the barge, the same kind of ease seemed to scent the nights. The barge passed through cities, along the countryside and through major events without ever disturbing the thick layer of ease between it and the rest of the world. Perhaps the reason was that, surrounded by the Nile as it was, the barge was protected from most disturbances by hungry crocodiles waiting, like logs, in the river.

I could relate, when I wasn’t stuck in my suburban bunker, I’d had parties that edged close to Eve Babitz parties and I’d certainly spent some time on the barge, in a Hollywood style sea city also much maligned.

I too was wrestling with my medicine. And while my Valentinos were mostly boys in Camiras and Camrys instead of Cadillacs and Lincolns cruising roads instead of boulevards slugging passion pop instead of pink champagne, Jacaranda’s manifesto rang true all the same.

A philosophy and a cautionary tale

These days I’m more attuned to Slow Days, Fast Company – The World, The Flesh and LA Eve’s suave collection of personal essays where the narration is older and wiser. In the late 90s though, it was fittingly all Sex and Rage, the original subtitle reading “Advice to Young LA” – Jacaranda both an embodied philosophy and cautionary tale.

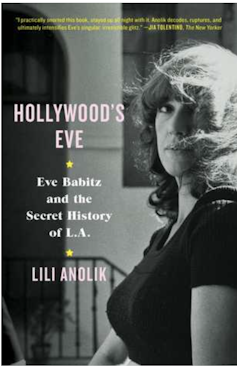

On the 20th December, Eve Babitz died from complications relating to Huntington’s disease. She had in the last decade of her life experienced a resurgence led largely by Lily Anolik’s 2014 article in Vanity Fair that later became Hollywood’s Eve a chronicle of Eve’s remarkable work and life story.

After years in the wilderness Eve was everywhere, the cool covers of her reissued books peeking out of totes or below manicured eyebrows on Instagram, her sex bomb reputation, talent and devil may care attitude something high filter, new gen girls wanted to possess.

On her late success Eve said, “It used to be only men who liked me, now it’s only girls,” a classic Babitz quip never as light on as it first appears.

Because Eve was always good at girls, some of the best scenes in Sex and Rage are when she’s with women, her acerbic agent from New York, her godmother, her sister or the luminous Summer a young woman she rescues from harm and takes on a cocaine fuelled road trip, the way she could zone in on a character in a couple of knockout lines:

Jacaranda decided Sunrise was so beautiful that nothing could hurt her. She was not like other people – all mortal and nose-blowy. Sunrise hardly said hello; she just breathed life into her encasement.

Maybe that’s why it took so long for the American literary establishment, who had denigrated her for so long, to wake up to bleeding sunset style of her genius.

Sally Breen, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Publishing, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To purchase on Amazon click on the image below.