Award winning photographer Russell Shakespeare explains the obsession: I’ve photographed shearers a lot over the years for a number of different publications. They’re an important and easily understood symbol for one of Australia’s most important industries; and there is a good deal of romance associated with them, historically and to the present day.

It’s romantic until you’re in the shed. And then it’s bloody hot hard work. It’s romantic in photographs and paintings, but in reality it is one of the hardest jobs you could ever do.

There is so much going on in the sheds. The thing you notice most is the noise. All the shearers have a portable radio or boom box, and it’s just blaring. Heavy metal. Something with a bit of a pump.

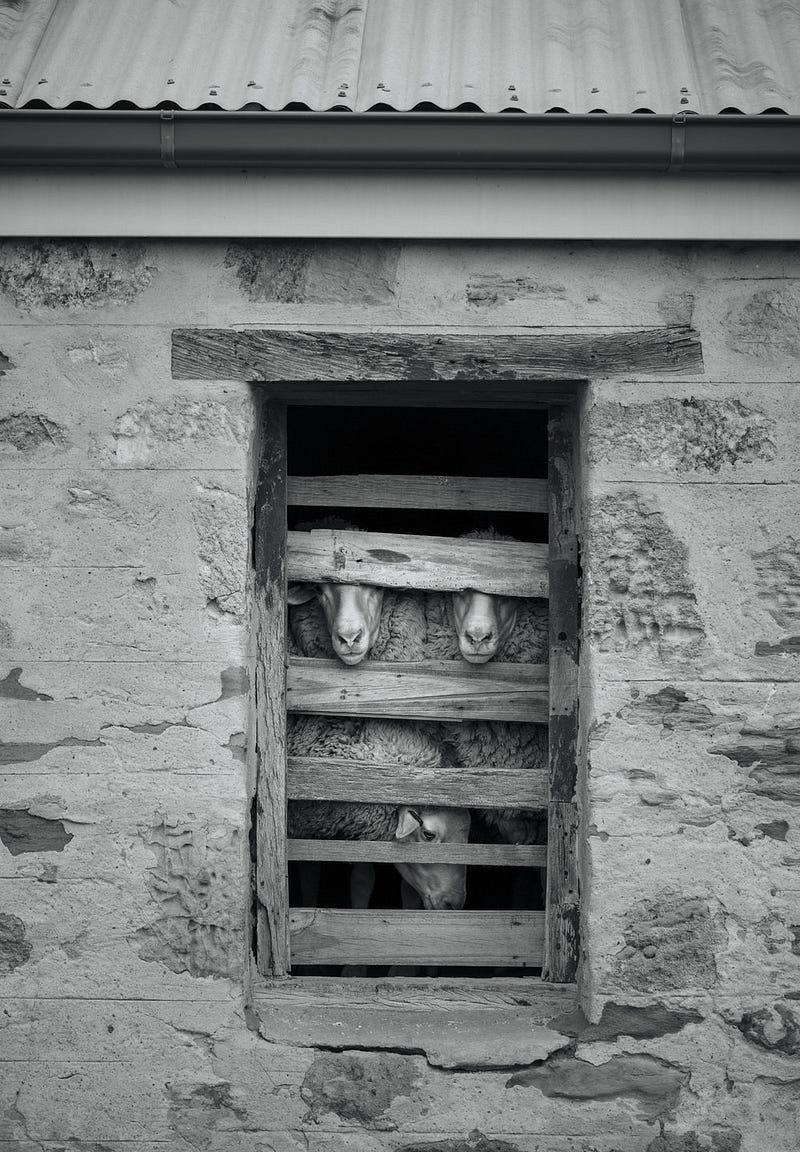

These first shots were taken at Bungaree Station in South Australia as part of celebrations for the property’s 175th birthday. It was established in 1841.

It’s a very traditional station. Old stone buildings. They still have a forge for all the metal work.

The shearing shed at Bungaree is an absolutely amazing shed. It is one of the biggest and best in the country. There’s a lot of room for the shearers. The stone walls keep everything reasonably cool.

The shearers are a real mixture. They’re essentially itinerant. They work in a gang, going from station to station.

It’s notoriously hard work, the hardest you can imagine. You are bending over all day. The sheep themselves are hard work, turning them over, all that.

Australia, it was always said, was built on the sheep’s back.

As the film Riding on the Sheep’s Back records, for a century, the wool industry gave Australia one of the highest living standards in the world. The economy rode high on wealth from primary exports. By the 1950s, wool was synonymous with the Australian way of life.

The selective breeding of Merinos, a breed which originated in Spain, resulted in sheep that adapted well to the arid interior of Australia and produced wool that appealed to the mills of England. From the early days the pastoral industry enjoyed a long period of prosperity.

Life on most of the stations is harsh.

The drovers, the property owners, the shearers, all came to symbolise what it was to be Australian. Tough. Independent. Laconic. Hard working.

The drovers, the property owners, the shearers, all came to symbolise what it was to be Australian. Tough. Independent. Laconic. Hard working.

The struggle to survive in the bush fashioned the character of the Australian battler.

The Land records that wool supply peaked in 1989. For years afterwards the industry languished.

But fortunes have changed once again.

Leading rural newspaper The Land reports that the industry is going through a Renaissance, and shearers are now in short supply.

A return to “natural fibres’ in our products and overseas demand for Australian wool is also driving the boom, with 73 per cent of the current season’s exports heading to China.

According to the NSW Department of Primary Industries, local wool growers have enjoyed a 55 per cent rise in their margins since 2016.

Ben Stace of the Australian Wool Network said the wool industry in general was plagued by a shortage of young people, but there were now hopes a more confident industry could turn that around. Profits were up at least 30 per cent in the region compared to the past few years, he said.

Champion shearer Ian Elkins said:

There’s never enough shearers.

Right now, there’s a spring in the step of everyone in the industry, it hasn’t been this good since I started almost 40 years ago.

Sheep numbers are rising too so we really need shearers.

There’s hardly any women in the shed.

They mostly sort the fleeces.

When they are shearing, they divide the wool into fine and not so fine wool. The women are much better at that than the blokes.

A shearing life is a pretty tough life. Eight hours a day bending over. Some of the rams are massive. A shearer can exert as much energy as a marathon runner.

The wool classers are on good money; $40 or $50 an hour. There are around 4000 shearers in Australia and about 100 of them are women.

An experienced shearer earns around $280 per 100 sheep.

“It’s hard work, from the first sheep the sweat starts pouring but it’s satisfying,” says young shearer Zac Patterson. “And, bloody oath it’s booming at the moment, the industry.”

Of course like many a male dominated workplace, sex is an ever ready subject of conversation, fantasy and humour; an aspect of bush life one of Australia’s greatest writers Henry Lawson caught in his poem A Shearer’s Dream:

O I dreamt I shore in a shearing shed and it was a dream of joy

For every one of the rouseabouts was a girl dressed up as a boy

Dressed up like a page in a pantomime the prettiest ever seen

They had flaxen hair they had coal black hair and every shade between

There was short plump girls there was tall slim girls and the handsomest ever seen

They was four foot five they was six foot high and every shade between

There was three of them girls to every chap and as jealous as they could be

There was three of them girls to every chap and six of them picked on me

We was drafting them out for the homeward track and sharing them round like steam

When I woke with my head in the blazing sun to find it a shearer’s dream

Gundoo Station in Outback Queensland is entirely different to the historic stations of South Australia.

For a start, it’s incredibly hot. The shed is made out of corrugated iron, not stone.

Because of the heat, a good number of the shearers sleep outside, in the backs of their utes, or on verandahs.

The nearest town is Isisford. According to the census the population has never exceeded 300.

These are good jobs from a photographer’s point of view.

The hardest thing about photographing shearers is just getting out of the way. The pace they are going at is so fast, you have to find a corner of the shed and stay out of the way.

They are going through a sheep every few minutes; the rouseabout is grooming up the loose wool off the floor, and because of all the lanolin, the oil, the floor can be slippery. You have to be aware you are not knocking someone over, or falling over yourself.

The space is quite a small area.

There’s very little small talk. People are working. During their break they are often sharpening their knives.

There’s a line from one of my favourite writers, Hemingway, and for some reason the characters in the shed remind me of it:

The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.

A good cook will make or break the camp.

Shearers have to have a good cook.

They are burning lots of energy in the heat of the sheds and food is all important. Big Breakfast, Big Smoko, Big Lunch, Big Dinner.

It’s not an ideal place for a vegan. It’s meat meat meat.

When they show up at a property they are usually given a sheep to slaughter.

If they’re not happy with the cook, the mood in the camp quickly becomes mutinous.

These assignments are adventures in themselves.

The thing about these stations is their absolute remoteness.

When you look out of the sheds, there is nothing but the land. Depending on the season, it can be pretty damn grim.

It’s still a long distance today, but I always think how hard it must have been in the old days, when they didn’t have vehicles to get there.

The other thing I notice is the clarity, they call it Blue Sky country. And at night the stars are intense.

Sometimes I think I’ve got a hard job, until I watch a shearer for eight hours. Then I can’t help but think how lucky I am.

Text by John Stapleton.

All images Copyright to Russell Shakespeare. He can be contacted through his website.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS