A TRULY VICIOUS HANGOVER fogged every sense, the morning I interviewed Anthony Burgess in London back in the 1980s.

There was no better place to be than the English capital, which was spinning through a centrifugal moment of cultural incandescence. Or so it seemed to a wide-eyed young journalist from Beyond the Pale — that is Australia.

The English have little but contempt for the convict barbarians from the Land Down Under. NOC. Not Our Class.

But I didn’t care.

One of the most fascinating, liberating things about journalism is that it offers the opportunity to pursue your heroes, to hunt the famous, to meet people in an interview situation you would never meet socially, not in a million years.

Anthony Burgess was exactly one of those people.

Everybody, no matter how famous or infamous, came to London to flog their latest product.

At the time I was yet to work out that only the lowest of the low in terms of the pecking order of journalists got slotted in at 9 am.

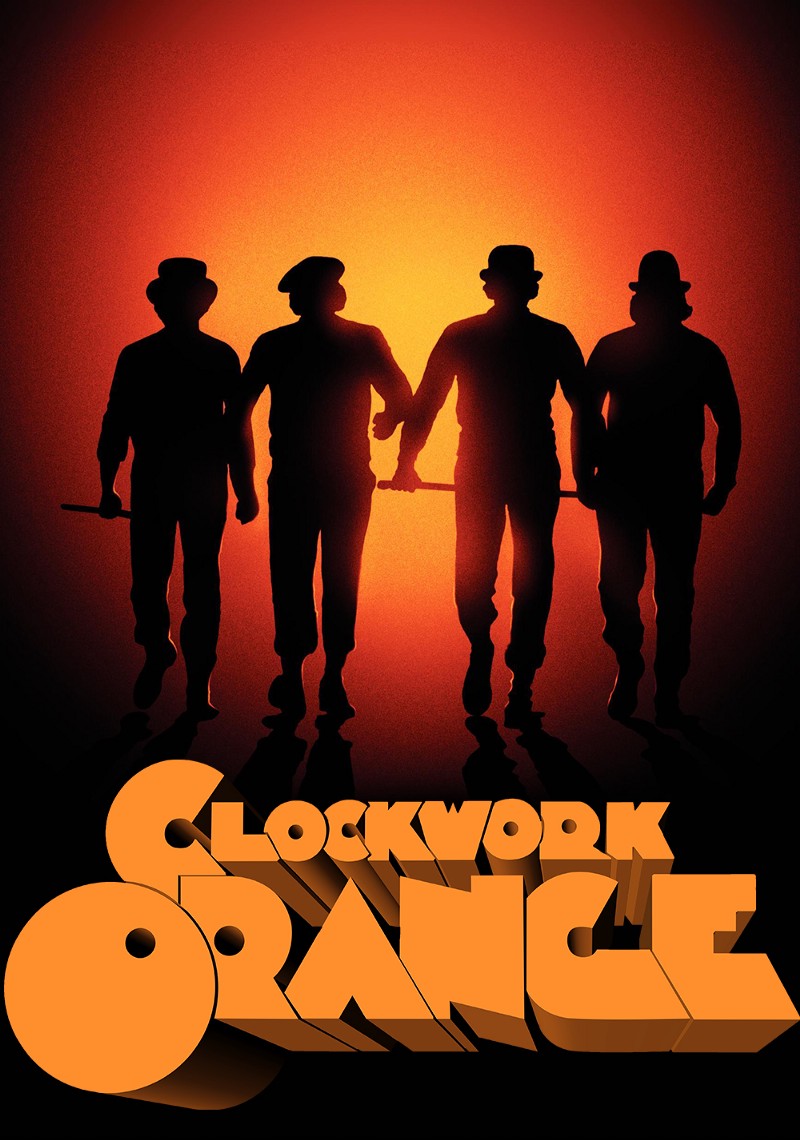

I had been to see the movie Clockwork Orange twice, and nodded off both times. My hard partying crew had expanded the old Australian saying: Never Trust A Man Who Doesn’t Drink.

Now I was interviewing one of the world’s most famous and most successful authors through a sheet of blinding pain; in the foyer of one of London’s many up-market hotels.

At the time I shared the disdain towards Burgess’s prolific output held by some of the decidedly less prolific, perhaps more thoughtful writers currently in play.

I was most influenced by Al Alvarez, author of The Savage God: A Study of Suicide.

Alvarez was particularly insightful on the subject of the poet Sylvia Plath, who gassed herself in W.B. Yeats old apartment.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I’m finally through.

The black telephone’s off at the root,

The voices just can’t worm through.

We called her Sylvia Platitude back in the 1970s, we loved her so much.

I became friendly with Alvarez after doing a story on him, and we would walk Hampstead Heath together talking about anything and everything.

The Heath, which was nearby his house, was well known as London’s largest gay beat. One thing we never discussed was the obvious going ons.

His disdain for Anthony Burgess, this was post the meandering door stopper Earthy Powers, knew no bounds.

But to quote from the published article itself:

In 1960, while working as a colonial civil servant in North Borneo, Burgess was told by his doctors he had an inoperable cerebral tumour and only one year to live.

“I realised a lot had to be done in that year, so I wrote six books,” he said. “I worked rather harder than I do now, 2000 words a day.

“Now I only do one thousand. Towards the end of that year, when I realised I was not going to die after all, I could get up at six, have the 2,000 words done by breakfast at ten, then have the rest of the day to myself.

“It’s a question of discipline: not so much discipline as allotting time.

To answer his many critics, Burgess told that most famous of literary publications, The Paris Review:

It has been a sin to be prolific only since the Bloomsbury group — particularly Forster — made it a point of good manners to produce, as it were, costively. I’ve been annoyed less by sneers at my alleged overproduction than by the imputation that to write much means to write badly. I’ve always written with great care and even some slowness. I’ve just put in rather more hours a day at the task than some writers seem able to.

Burgess had just penned his book Ninety-nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939; along with another in his Shakespearean series titled Enderby’s Dark Lady, or No End of Enderby.

Indeed, after I had waded through the series, there did indeed seem to be no end to Enderby.

On the other hand, Ninety-nine Novels had created a predictable furor in literary circles, promoting the publication of counter lists. The English sniffed.

As quickly became evident when I asked him about the sometimes excoriating commentary accompanying the book’s publication, Burgess was hugely enjoying the controversy over which books should and should not be included in a list of the 20th century’s best fiction.

The criticism was water off a duck’s back. The author of A Clockwork Orange was already a multi-millionaire. Nothing could touch him but time itself. Critics were just mosquitoes as far as he was concerned.

“The Government cannot be concerned any longer with outmoded penological theories….Common criminals…can best be dealt with on a purely curative basis. Kill the criminal reflex, that’s all.” A Clockwork Orange.

Not even a coffee

In those days, going through another phase of drinking and partying in the London clubs much of the night, particularly the world famous nightclub Heaven, I wasn’t always at my best at 9 am.

But then neither were the authors. Except for the wide-eyed, sober, bustling Anthony Burgess.

I was hungry after a night on the dance floor and alcohol sweat was defying the hotel’s air conditioning. I made it very clear I could have done with coffee and some breakfast.

No such luck.

Burgess had already breakfasted in his room and had no desire for any further repast.

The interview ended up being conducted on a couch in the ostentatious, chandelier dripping foyer.

The public relations woman sat perkily next to Burgess throughout, occasionally trying to facilitate the conversation.

She began by explaining to Burgess, and I heard her regurgitate the line I had sold her, that I was writing for The Australian Financial Review, which was that country’s equivalent of the much revered Financial Times.

The Financial Times, then published distinctively on pale pink newsprint, was one of England’s most prestigious newspapers and an organ any PR flack would like their subject to be showcased in.

Unlike the left wing Guardian, at least the readership of stockbrokers, investors and company directors had the money to buy whatever was being promoted.

Do these people dream about their futures?

“Who would want to be a critic?” Burgess demanded to know in that London foyer, in what was no doubt a well rehearsed line. “Do these people sit in school and dream about their futures and think, yes, that’s what I want to be, a critic. Is that all their dreams are made of?”

As for the controversy, all the better. You had to start somewhere, Burgess shrugged. The book had promoted debate and that is what it was intended to do. And hopefully it had got people reading more books.

Although I had not enjoyed the Enderby books I dutifully asked Burgess about what was hopefully the last of them.

But it was Nine-Nine Novels that set him alight.

Written in a fortnight and published in two months, this was a record even for him.

There in that overlit foyer he declared

There in that overlit foyer, amidst a blinding hangover which seemed to overtake the room, he declared:

The rapidity with which I wrote it and the nature of the exercise meant that it must be a tentative book. Even now, two months after British publication, I wouldn’t agree with all the choices. On some of the marginal books I would shift my position.

But this list at least give us a chance to take stock. There are so many thousands and thousands of books published every year people have to be told what to read. They need advice now more than ever. Possibly these are some of the best books. Let’s at least think about it. I don’t believe the exercise does anyone any harm.

When the interview wound up after forty minutes which seemed which seemed to last for several historical epochs I made my way across the football field of a foyer and out into the London streets.

Never a big one on sartorial splendour, I hadn’t bothered to dress up for the interview, and didn’t possess the clothes anyway, but the sight of my shambolic self in the foyer’s many mirrors did nothing to boost self esteem.

Not that Burgess Could Talk

As I stepped down from the mezzanine level and headed towards the hotel’s revolving doors, I saw Anthony Burgess and the public relations woman staring after me quizzically, and then burying their heads together.

Not that Burgess could talk. In the late 1950s he was dismissed from his position as a teacher in Brunei, and as an excuse claimed to have had a brain tumor; a tumor that was never found.

Burgess’s storytelling abilities were well known to extend to his own history. His biographers attribute the incident to the author’s notorious mythomania.

He was said to be suffering from the effects of prolonged heavy drinking and associated poor nutrition, of overwork and professional disappointment.

There was no air of disappointment about Burgess when I met him.

Indeed, Burgess could hardly have appeared more affluent, stolid or certain of himself.

While Burgess prepared for another interview before flying back home to Monaco, I headed back to an increasingly frustrated lover, and to another night of pointless carousing and implausible excuses.

As I entered the over-white light of the street, I had a stab not just of disorienting pain, but of envy for the workers in the street, the shopkeepers behind their counters, the bus driver passing by, the legal secretaries with bundles of documents rushing to their offices.

I envied them their comfortability, normality, singleness of purpose, their apparent certainty in who they were and why they were.

Scattered to the four winds, as if there were several personalities inside waiting to be born, I had no idea who I was or where it would all end.

In a sense I didn’t want to be anything or anyone at all. But thereby hangs another story.

The paper loved the story, and at least as far as interviewing famous authors was concerned, I was now well on my way.

We throw off the old garb, and step into the light. We signal frantically for years and then find others. We stop hiding. We outflank our many enemies in one magical instant. Before the world rolls over us.

Anthony Burgess died in 1993 at the age 76 of lung cancer.

This is an extract from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as a journalist on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.