By Brigid Magner, RMIT University

The Black Summer bushfires may have ended, but the cultural cost has yet to be counted.

Thousands of Aboriginal sites were likely destroyed in the 2019 bushfires. But at present, there is no clarity about the numbers of precious artefacts lost.

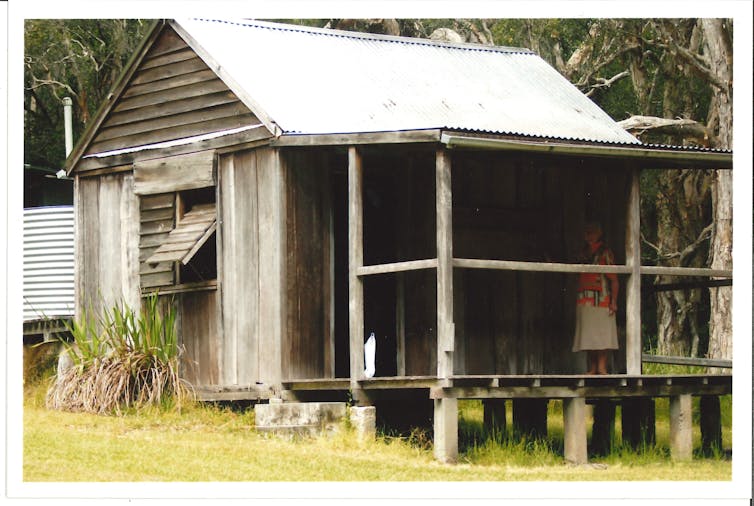

Though recent by comparison, relics from Australian literary heritage have also been reduced to ash. Last year’s bushfires destroyed a hut built specially for author Kylie Tennant (1912–1988) at Diamond Head, and many High Country huts associated with A.B “Banjo” Paterson’s The Man From Snowy River.

Thankfully, NSW Parks and Wildlife Service are making plans to rebuild Kylie Tennant’s hut. But after this devastating loss, it’s impossible to ever fully recreate the authentic atmosphere of Tennant’s writing retreat.

The undeniable romance of Kylie’s hut

Tennant was best known for her social realist studies of working-class life from the 1930s, including her Depression novels The Battlers (1941) and Ride on Stranger (1943).

During the second world war, Tennant moved to Laurieton with her husband and their daughter Benison, and lived there until 1953. At nearby Diamond Head, she met Ernie Metcalfe, a returned serviceman from the first world war and well-known local bushman.

Read more: Reading three great southern lands: from the outback to the pampa and the karoo

Metcalfe felt Tennant had paid him too much for the land she bought from him, which was partly why he offered to build the hut. Bill Boyd, who later restored the hut, remembers

Kylie would insist on paying him […] she only paid him about 25 pounds which was a lot of money in that time.

Metcalfe was memorialised in her non-fiction book The Man on the Headland (1971). From the beginning, fire played a part in the hut’s life.

The first summer, as though Dimandead [Diamond Head] had made a sudden bid against this new invasion, a fire leapt the creek and came so close to the house that one window cracked in the heat.

Ernie fought the fire single-handed and when we arrived he was standing sooty with ash in his beard in a blackened desert with the house safe in the middle.

While appearing to be an ordinary bushman’s dwelling, “the romance” of Kylie’s Hut was “undeniable”, according to Andrew Marshall, a marine wildlife project officer in the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service. It’s fondly remembered by locals, tourists and aspiring writers who have visited since the 1980s.

Its location in a campground was unique because it quietly coexisted with holidaymakers rather than being relegated to a specially demarcated, curated space. However, this lack of protection left it exposed to the elements and the predations of climate change.

Read more: ‘Like volcanoes on the ranges’: how Australian bushfire writing has changed with the climate

Protecting Crowdy Bay National Park

In 1976, Tennant donated the hut and the surrounding land to Crowdy Bay National Park, partly to try to protect the environment from ongoing rutile mining.

The creation of the Crowdy Bay National Park was facilitated not only by Tennant’s gift, but also by the earlier dispossession of the Birpai peoples and the re-zoning of their land.

It’s also important to acknowledge Tennant’s tendency to erase the Indigenous presence in this book. In the opening chapter, Tennant writes that Diamond Head’s “aborigines were gone, all gone, like the smoke blown from their fires”.

The erroneous belief that previous inhabitants had “disappeared”, meant the story of Tennant and Metcalfe’s friendship, symbolised by the hut, effectively obscured earlier stories of the Traditional Owners.

Restoration worthy of preservation

Local bush carpenter Bill Boyd substantially refurbished Kylie’s Hut in the early 1980s. A master of old forestry and timber working tools, Boyd used the restoration of Kylie’s Hut as a way to share his knowledge of the uses of broad-axe and adze (an axe-like tool with an arched blade).

Aside from its association with Tennant, the hut has additional significance because it was built using “unpretentious construction techniques” and displays “a unity of form, design and scale”, according to Libby Jude, a ranger from the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service.

It was composed of “strong, natural textures” associated with the fabric of the place in which it stood. And the specialised restoration methods Boyd used are heritage practices that are themselves worthy of preservation.

Boyd also passed on his knowledge to younger carpenters while restoring many of the High Country huts, some dating back to the 1860s and associated with The Man From Snowy River. Most of these were also razed by the recent bushfires.

Members of the Kosciuszko Huts Association have expressed their desire to restore the huts, but a conversation about when and how they could be reconstructed will be well down the track.

Australian literary heritage is often forgotten

Unlike the United Kingdom, where literary properties are routinely listed on maps, Australia tends not to proudly celebrate sites related to its writers.

Aside from the work done by the National Trust, literary societies and enthusiasts in regional communities mostly drive the protection of Australian literary sites.

Read more: Ten of Australia’s best literary comics

Ideally, there should be a more coordinated approach to our literary heritage which could identify vulnerable structures and take steps to ensure that, wherever possible, they’re not wiped out by natural and man-made disasters.

The memorialisation of Kylie’s Hut, which began in the 1980s as a response to her book The Man on the Headland, rendered black history peripheral to the central story of bushmen like Metcalfe living in the area. Nevertheless, it was an accessible literary site stimulating awareness of aspects of our cultural history, which might otherwise remain almost completely unknown.

Brigid Magner, Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS