This is not your standard white-girl-in-Africa tale. I fed no babies, I built no schools, I saved no rhinos. Self-discovery came a distant second to self-preservation on this particular adventure.

So says Kirsten Drysdale, who is better known as a charming, quick witted, upfront Australian television personality than as an author.

Her first book, I Built No Schools in Kenya, is published by Penguin Random House this month.

Back in 2010, between gigs, Drysdale claims she was was tricked into going to Kenya, a place she had never thought much about.

A friend called with a job offer too curious to refuse: a cruisey gig as a dementia carer for a rich old man. All expenses-paid, plenty of free time to travel or do some freelance reporting.

Only Kirsten’s friend hadn’t given her the full story. It was only on arrival in Nairobi that she discovered the rich old man’s family was fighting a war around him, and that she would be on the front line.

Caught in the crossfire of all kinds of wild accusations, she also had to spy on his wife, keep his daughter placated, rebuff his marriage proposals, hide the car keys and clip his toenails, all while trying to retain her own sanity in the colonial time warp of his home.

“I didn’t really know what I was heading to,” Kirsten told A Sense of Place Magazine. “I didn’t go with the intention of writing about it.

“I came back and started telling people the story, and people said I should write a book.

“I was a bit hesitant. I was in my twenties when I went and I have a general rule that nobody under thirty should be writing a memoir. But I broke my own rule.

“It is a memoir about one year, and a very very bizarre experience. I hope the story is not so much about me as about what happened; the world I was in.

Of course Nairobi is more often in the news for terrifying terrorist attacks and associated mayhem than as a place for a coming-of-age adventure story.

While Drysdale was caught inside a luxury mansion caring for a dementia patient, a time warp of colonial Kenya, the Kenyan army was invading Somalia and Al-Shabaab was threatening attacks.

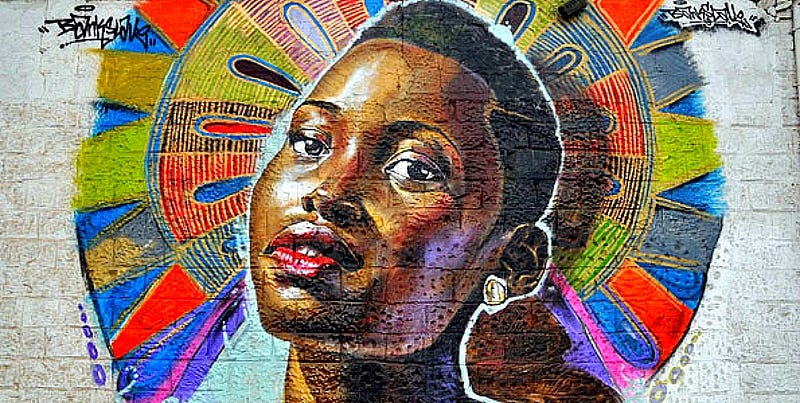

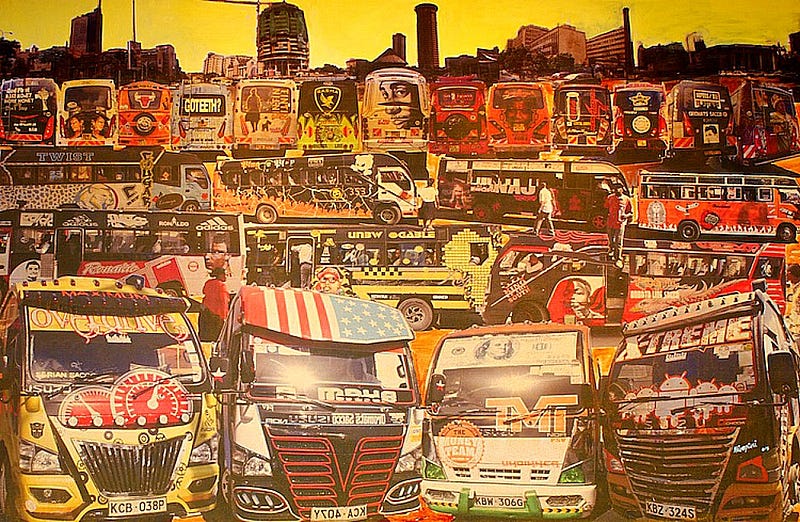

“As soon as you drove through the gates you were in modern Nairobi,” she recalls. “It was an incredibly vibrant place. There is so much more going on in Africa than we tend to see.

“You have extreme poverty, but also a burgeoning middle class.

“If you went to a shopping centre it was like being in a mall at home. There are teenagers eating frozen yogurts, buying fashionable clothes, sitting on their phones.”

But terror is striking home.

“It’s strange and chilling,” Drysdale says. “I know so well the places where these things are happening.

“I remember the shopping mall attacks of 2013. It was weird to watch the coverage of it. A lot was shot on mobile phones from people stuck inside.

“Cafes, table and chairs where I had coffee with people, where it had been a peaceful ordinary place. It was incredibly shocking, and very very sad to see that happening in what was one of the more promising sides of Kenya.”

I Built No Schools in Kenya is a travelogue-tragedy-farce about race, wealth, love, death, family, nationhood, sanity, tranquilizers, monkeys, whisky, dementia and a bygone world.

“I found it a very difficult story to tell in book form. The whole way through I felt and still feel it would have been easier to write as a television script.

“Partly because of my day job, I work in TV.

“And so much of the story I wanted to tell was visual.”

Below is an extract.

The Situation: Nairobi, Kenya.

So here’s how it is: I’m a live-in carer for Walter Smyth. He is very rich, very old, very sick and very senile.

Over the next eight years, dozens of people will occupy this role. Most of them won’t last long. Some of them will literally run away in the dead of night after just a few weeks.

In comparison, I’ll be here quite a while. Eleven months all up. But I don’t know that yet. I can’t imagine what’s to come.

Walt doesn’t know it, but he has employed three women to look after him. There’s me; there’s my mate from high school, Alice; and there’s Millicent, a sweet old woman who is very into God. The three of us tag-team around the clock in eight-hour shifts, supervising Walt’s meals, his morning walks, his medication, his showers, his shits and his sleep. Alice and I are also supposed to spy on his wife, Marguerite, for his daughter, Fiona, who thinks Marguerite’s trying to kill him, even though she’s not.

I didn’t know the whole imaginary-murder-surveillance thing was part of the job description until I got here.

Millicent is an old family friend of the Smyths, a fellow former colonial, a couple of decades Walt’s junior. She blends in a bit better than Alice and me.

We’re in our mid-twenties and come from Mackay, a town in regional Queensland. We’ve had to learn the ways of this world.

The Kenyan household staff are just getting on with things as best they can. Most of them have been working for the Smyths for a very long time — though I don’t think it’s ever been quite the punish it is now that Walt’s sick and surrounded by a team of meddling mzungus (Europeans). Not that they ever complain.

Walt’s house is in one of Nairobi’s nicer suburbs. It’s one of the area’s older, more modest homes, surrounded by hedge-hemmed mansions boasting tennis courts and swimming pools. Someone very important has a place just down the road — in the evenings you can hear their helicopter coming in to land. When I jog past their high gates I’m watched by camera lenses and rifle sights, and barking dogs that scare me over to the other side of the road.

A Dying Breed

As for Walt himself — well, he’s an anachronism. An old-school colonial from early establishment stock. His father was one of the first white men out here, one of those guys you imagine arriving with a sack of Union Jacks slung over his shoulder, marching along in a pith helmet from the coast to the Nile, laying claim to land with every few steps on behalf of the Empire and promising to ‘civilise’ the ‘natives’, as though there’s anything ‘civilised’ about subjugating people in their own country.

On Walt’s mantelpiece is a photograph of Teddy Roosevelt when he came to Kenya on a hunting safari in 1909. Except it wasn’t called Kenya back then; it was still the ‘British East Africa Protectorate’, one of the many pink patches on the map.

So you see, these people are a big deal around here. At least, they used to be. Modern-day Kenya barely knows or cares that they exist. Old colonials are literally a dying breed.

Walt has so much money it will never run out. It’s partly inherited and partly self-made. He was a farmer, of tea and coffee and cattle. I’m told by the household staff that he worked hard to turn unproductive land around, and was nearly bankrupted doing so.

Daniel arap Moi, Kenya’s second president, admired Walt’s farm so much he compulsorily acquired it from him in the 1980s. Walt was lucky to receive a good price. Independent Kenya, for the most part, made a point of being relatively gentle with its former colonial masters. Whether that was for better or worse depends on who you speak to.

It’s 1942. It’s 1985.

Now Walter Smyth’s in his eighties, and his mind is falling apart. He’s got vascular dementia: a demolition team of tiny strokes and little wrecking balls of sticky protein are destroying his brain, leaving a rickety frame of consciousness behind.

Walt grasps at the past and hallucinates much of the present.

His body isn’t quite as shaky as his mind, but he does have a pacemaker and a dodgy liver and kidneys that need keeping an eye on. Most days, Walt thinks he’s in England, where he lived half his life. He thinks it’s 1942 and he’s collecting Second World War bomb shrapnel from the fields near his school. Or he thinks it’s 1985 and his mother has just died and he needs to get his suit ready for her funeral in Dover.

Some days he does think he’s in Kenya — but that it’s 1956, in the middle of the Kenya Emergency, and he’s up on the tea farm, and needs to drive to the city for supplies, and might be attacked by Mau Mau terrorists on the road to Nairobi, and so needs to find his guns.

He never thinks it’s 2010 and he’s already at his house in Nairobi, the one he’s had for thirty years. Even that lion hanging on the dining-room wall doesn’t jog his memory. You’d think it would — he’s got scars all the way down his legs from its claws. Those yellow teeth were sunk deep into Walt’s foot when he finally managed to unjam his rifle and send a bullet through the side of its skull. Now the lion watches him eat, its jaw frozen in a silent roar.

There’s no good reason for my being here (though there are plenty of bad ones). I have no nursing experience. All I know about dementia is what I saw as my grandmother’s mind crumbled to dust in the latter years of her life: the way she would conduct orchestras at the dinner table using chicken bones as batons, or cut pictures of puppies out of tissue boxes and glue them to the back of her couch because they were ‘sweet’.

More than anything else, this whole story is the result of cosmic timing.

In September 2010, I’d just started working in television, back home in Australia. But Hungry Beast — the show I worked on — had finished and we weren’t sure it would get another season.

Having uprooted my life and moved to Sydney for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of working for Andrew Denton, I was in a weird place.

In one sense, I felt I had the world at my feet. But I wasn’t at home in Sydney. I was lonely, a bit lost, and in hindsight probably mildly depressed.

Just as I’d decided to move back to my family’s farm in Mackay for a while, Alice called from Nairobi with a somewhat intriguing proposal. She’d been hired by the Smyths through a carers agency while she was living in London, and when they decided to return to their home in Nairobi, she agreed to go with them. But the job was too much for one person alone — they needed more help.

‘They just want someone white, female, slim and switched on,’ she said.

‘Those first three seem a bit … icky, dude.’

‘No, no, no — it’s not like that. The thing is, we’re living in the house with Walt. So even though he doesn’t know what’s going on, we need to look like people he might have had in his home throughout his life. That’s why they can’t hire black carers — he’d never stand for it. And he’s terrible with fat people. Would comment on their weight all the time. Like, repeatedly, ’cos he forgets what he’s just said. It’d be way too awkward. But with me, he just assumes I’m some friend of the family or whatever. You’d fit right in.’

‘He sounds like a total arsehole.’

‘Oh no, he’s really quite sweet! Well, most of the time. I mean, obviously he’s a bit racist. And sexist. But that’s to be expected. He’s a product of his time! And look, he can get a bit cranky and frustrated now and then, but it’s easy enough to calm him down by flirting with him and making him laugh.’

‘Mm,’ I said, slightly revolted. ‘And all we have to do is make sure he doesn’t run off and get lost?’

This piece was written by John Stapleton, editor of A Sense of Place Magazine. A collection of his work is being constructed here: https://thejournalismofjohnstapleton.blogspot.com/