America’s Secret Military Base in Central Australia

Tom Gilling

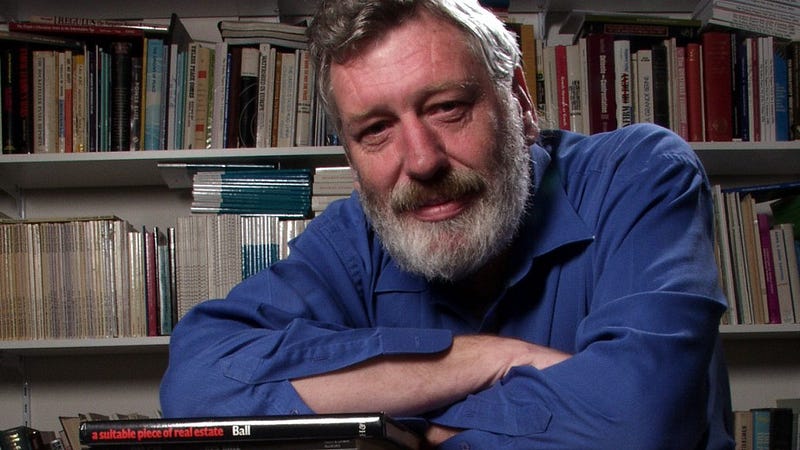

Des Ball, or Professor Desmond Ball as he was officially known, passed away from cancer in October, 2016. An Australian expert on defence and security, he was admired within the international intelligence community, where he was credited with successfully advising the US against nuclear escalation in the 1970s.

Ball was a lovely man, and unlike most academics who regard news reporters as their intellectual inferiors, always helpful to journalists, which is why he was so well liked by them.

Ball always made good, pithy copy. And as a military strategist and author of more than 40 books on military intelligence, was entirely credible.

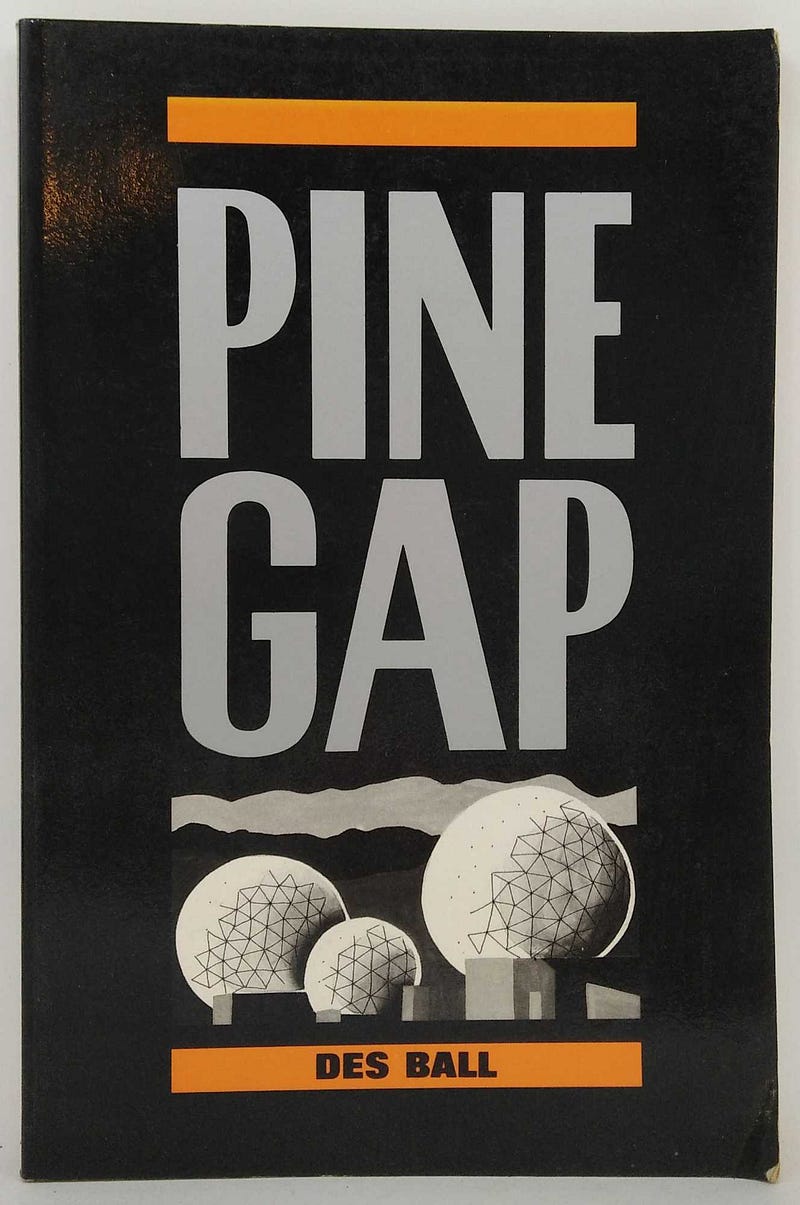

Des Ball first came to the attention of the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) an opponent of the draft for the Vietnam War in Australia and was arrested for protesting against it. He endured prolonged surveillance at their hands. From 1966 he was a “person of interest” for ASIO, particularly following his inquiries into the Pine Gap secret tracking facility and was taken to court after the publication of A Suitable Piece of Real Estate in 1980.

Here is an extract from Tom Gilling’s new book Project Rainfall: The Secret of Pine Gap, published this month.

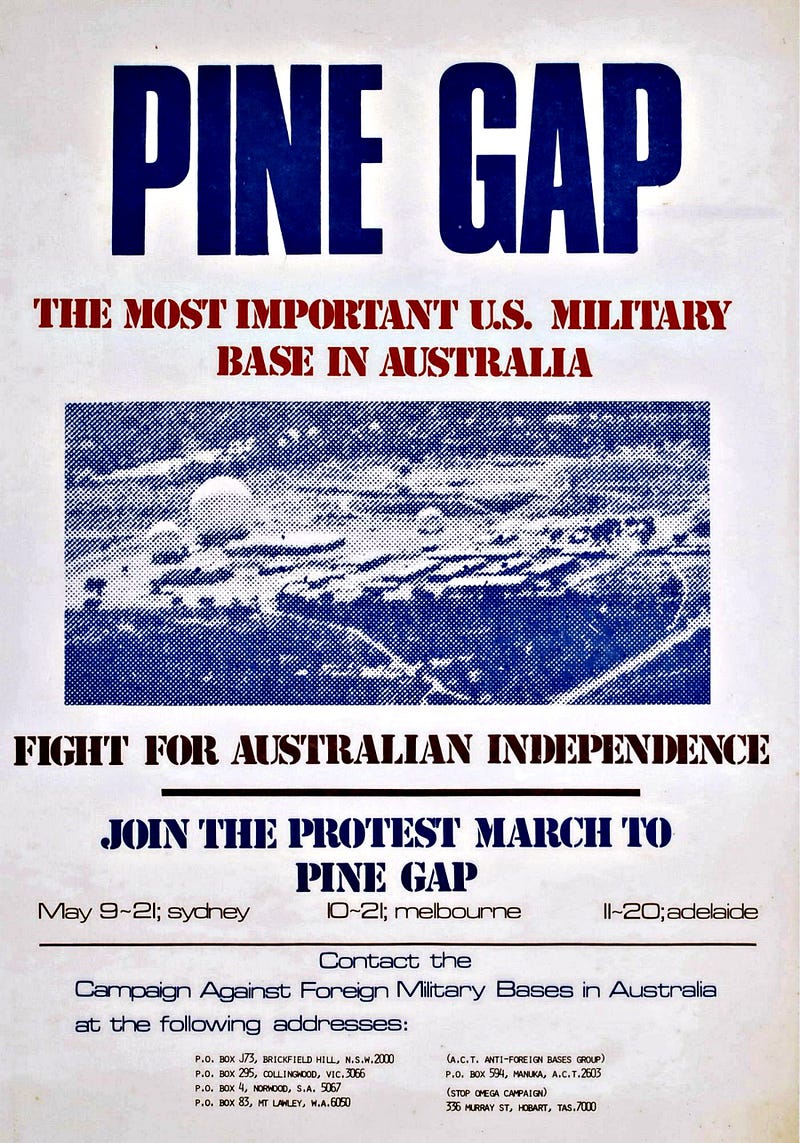

Reds, ratbags and radicals

On 19 October 1977, the eleven-year-old Pine Gap agreement

between the US and Australian governments was extended by

an Exchange of Notes.

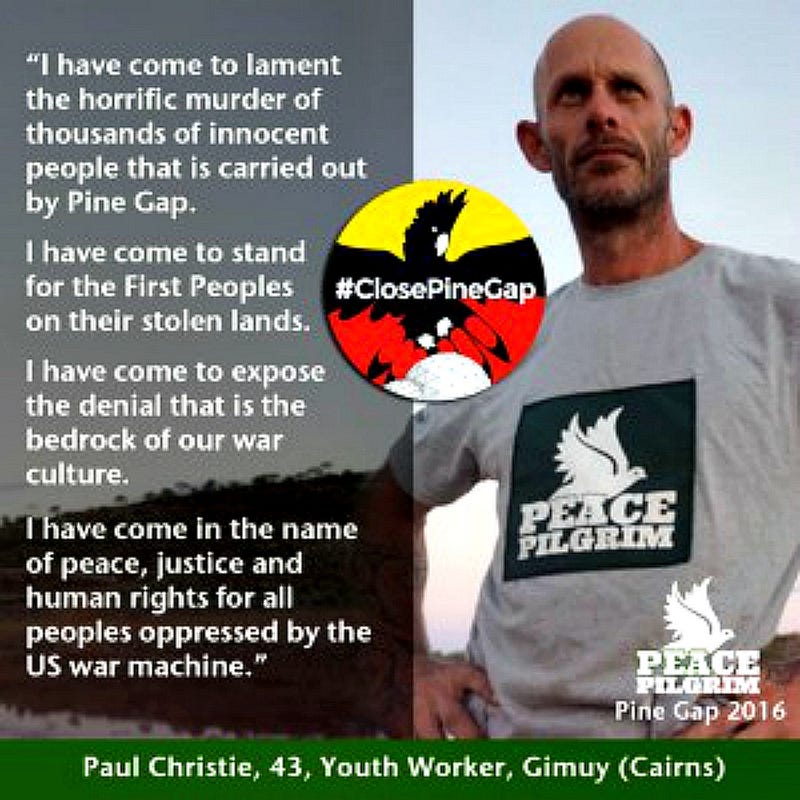

Once the new agreement had been in force for nine years (i.e. after 19 October 1986) it could be terminated by either party with one year’s notice. Officially, the base was now secure, at least for the next decade. But the voices questioning its usefulness, its safety and the morality of its

existence were growing louder.

For many years, the best informed and most troublesome

of the base’s critics had been Des Ball and his colleagues at the

Australian National University.

According to Paul Dibb, then a senior intelligence official, later an Emeritus Professor in Defence Studies, Ball’s increasingly prolific writings about Pine Gap were viewed by the Defence Department, and especially its bulldog secretary, Sir Arthur Tange, as ‘aiding the enemy’.

When Dibb left the department to work at the ANU on his book The Soviet Union: The incomplete superpower, Tange’s successor, Bill Pritchett, told him, ‘You’ll be working along the corridor from that Des Ball and we’ll be watching you.’

Dibb described the department’s obsession with Des Ball as ‘paranoia’, but its consequences were real enough.

The National Archives has two ASIO files on Ball dating back to the time when he was a student at ANU. Some of the material consists of newspaper cuttings but the files also contain detailed reports, many stamped ‘Secret’ and partially redacted, that show how Ball had been kept under ASIO surveillance at least since 1966, when he was charged with ‘offensive behaviour’ during an anti-Vietnam war demonstration in Canberra.

As a final-year political science student, Ball had aroused further suspicion through his collaboration with Robert Cooksey on an article about Pine Gap published in the Australian Quarterly in December 1968. A five-page letter written in April 1969 by the then director-general of ASIO, Sir Charles Spry, in response to a ‘verbal request’ by Tange’s predecessor, Sir Henry Bland, indicates how seriously the government and ASIO took the activities of Ball, Cooksey and other Australian academics interested in ‘defence installations and defence policy’, many of whom were alleged to ‘have publicly known radical sympathies and . . . contact with the Communist Party of Australia’.

In 1969 Cooksey was a lecturer in political science in the ANU’s School of General Studies. Ball would go on to become head of the ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, which in December 1968 had been the subject of an article in the communist Australian Left Review. The article, by Monash University lecturer John Playford, was described by Spry as having been written ‘with assistance from sources which are not normally available to academics’.

In his letter to Bland, Spry speculated that Playford had been ‘acting as a disinformation agent on behalf of the Russian Intelligence Service’.

Noting the number of Australian academics with ‘radical’ left-wing political sympathies writing about Pine Gap, the ASIO chief advised Bland that their activities were intended ‘to embarrass the Commonwealth Government in its field of defence research and analysis and also to isolate and embarrass any academics who have contact with your Department, and . . . to ensure that the numbers of such people are limited’.

The linking of ‘communists’ with Pine Gap rang alarm bells in the security services of both Australia and the United States. Ball never doubted that Bland’s request for information on him was prompted by the CIA’s then chief of station in Australia, Raymond Villemarette.

In A National Asset: 50 years of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Ball writes that the CIA ‘was concerned that my research might reveal both its role and the existence of its geostationary SIGINT satellite program’.

(In the same essay Ball admits that he did not know the CIA was in charge of Pine Gap until Brian Toohey revealed it in November 1975 in the Australian Financial Review.)

Spry’s suspicions of Soviet infiltration into the ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre were not as outlandish as they seemed. In 1999 News Weekly, published by the National Civic Council, alleged that ‘for over two decades, the KGB has regarded SDSC as a key target area in which they can recruit agents of influence’ and gain access to agents ‘in Defence and

the intelligence community’.

In his essay in A National Asset, Des Ball recalls that Lev Sergeyevich Koshlyakov, the ‘energetic KGB Resident in Canberra from 1977 to 1984’, was said to have been ‘well known to key senior Centre staff’, although Ball did not believe he ever visited the centre. Another Soviet diplomat, Igor Saprykin, whom ASIO suspected of being a KGB officer, did visit the centre. But the KGB was not alone in trying to cultivate the staff of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre.

According to News Weekly, two of the centre’s ‘directors’ were ASIO sources. It is likely that at least one of the pair was feeding Spry information about Cooksey and Ball.

In May 1969, a month after Spry’s letter to Bland, the ASIO chief asked his Victorian regional director to conduct a ‘birth check’ on Ball. The following month Ball took part in a noisy protest against the visit of the South African minister for economic affairs, Jan Haak. An ASIO report lists Ball and Cooksey among the demonstrators (‘a few . . . with their faces painted black’) standing outside the Hotel Canberra and ‘shout[ing] slogans such as “Go home Haak — take Gorton with you”’.

On 2 July 1969 the Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Age published the first of a series of articles about Pine Gap by Cooksey and Ball.

Under the headline ‘Pine Gap: What is its purpose?’ the two authors described what they considered to be the ‘two ongoing functions of Pine Gap’, namely the reception of information from reconnaissance satellites (especially early warning satellites) and the control of space-based anti-ballistic missiles.

In the second article, published the following day, Cooksey and Ball argued that Pine Gap would be a ‘priority target’ in a global nuclear war and that ‘major cities, especially Sydney and Melbourne’ would also be hit by Soviet missiles. It is more than possible that the Soviet Union might become aware . . . of a successful development program of satellite-ABMs from Pine Gap. Then it might issue an ultimatum to the Australian Government to dismantle the installation, or suffer a nuclear attack on an Australian city. Or perhaps it would launch a preventive [sic] strike against Pine Gap.

In the final article, ‘Real reason for veil of secrecy’, Cooksey and Ball questioned the value Australia was getting from the US alliance and argued that the ultimate beneficiary of Australia’s hosting of Pine Gap was the United States.

‘Under Australian secrecy,’ they wrote, ‘American Administrations can undertake projects which are difficult to handle at home.’ The article concluded: In any event, Pine Gap is operational and likely to remain so. As have other peoples, Australians will no doubt learn to live with the prospects of nuclear war.

But it is no comfort that the Government took such a critical decision as agreeing to the construction of the Pine Gap installation, privately and probably ill-advisedly, without consulting Parliament or allowing public debate.

Nor does it help that Pine Gap serves only the global strategic interests of another country — even if that country is the USA.

Although the three articles ran to a total of several thousand words, they contained relatively little hard technical data, and probably nothing that was not already available from published sources in the United States. But Cooksey was preparing to raise the stakes.

A declassified document in Ball’s ASIO file reveals that on the evening of 10 September 1969 a source inside the ANU informed ASIO that Cooksey had announced his attention to ‘try and visit the Pine Gap installation later this week’. This is the visit that Cooksey would later write about in the Age. The then opposition leader, Gough Whitlam, had visited Pine Gap a week earlier but had been prevented from entering the technical areas. Cooksey had submitted a written request to the defence department to be allowed to visit but permission was refused.

According to the ANU informant, Cooksey planned to leave Canberra on 10 September before travelling to Alice Springs via Melbourne and Adelaide. His ‘exact mode of travel’ was not known, but Cooksey had made it known ‘in University circles’ that ‘funds had been made available for his trip’. The informant did not know the source of the funds but considered it ‘most

unlikely’ that the money came from the ANU.

From the moment he arrived in Alice Springs, Cooksey was under surveillance. The departments of defence and supply had been warned of his arrival and a defence official, Mr F.S.B. Appleton, DSO, was on hand to confirm that the ANU lecturer landed at Alice Springs airport ‘at about midday’ and checked into a local hotel. It was also learnt that ‘he was using an Avis rent-a-car and the suggestion was made in press circles that funds had been made available to him by the “Australian” [newspaper]’.

The ANU informant had picked up some talk around the university that Des Ball was planning to accompany Cooksey (in fact Cooksey made the trip alone). ASIO’s assistant regional director for the ACT believed the plan was ‘to attempt to gain entry into the Joint Defence Research Station at Pine Gap’.

At 1000 hours on 15 September:

Mr [assistant regional director, ACT, name deleted] . . . stated that the most recent information concerning COOKSEY was that he had spent the weekend prowling around Pine Gap. He made several unsuccessful attempts to enter the area, including an attempt to crawl under the Springs had also refused to fly him over or near the area.

The question of financing . . . [the] trip had been raised in Canberra, and it had been suggested that ‘The Age’ may be providing the money.

In what was described as an ‘encounter’ with a Commonwealth Police officer at the eastern boundary fence of the joint facility, Cooksey gave his name and also ‘mentioned the name of Desmond John Ball when speaking of the articles that have been published in the Melbourne Age . . . This was the only time that Ball was mentioned.’

The documents in Ball’s ASIO file suggest that during his visit to Alice Springs, Cooksey was followed everywhere he went. While in town he asked for the Lands Office to be specially opened so that he could buy maps of the Pine Gap area.

According to a report, the Lands officer ‘met Cooksey at the Lands office and showed him a copy of the normal Alice Springs District Map scale 1:250,000 produced by National Mapping which is for public sale . . . at this time a copy was not available for sale, and the Lands officer was not agreeable to recalling a staff member to duty at that hour to produce a black and white print of same. This map shows the access road from the South Road to the Pine Gap entrance to the Prohibited Area. It does not indicate the boundaries of the Prohibited Area.’

Thwarted in his efforts to get inside the installation, Cooksey left Alice Springs by TAA Flight 555 at 12.45 pm on 14 September, apparently because of ‘lectures he had to deliver at the ANU on the afternoon of 15 September’.

After the encounter with the policeman Cooksey reportedly said that he had ‘no intention of making a martyr of himself by illegally entering the JDSRF Prohibited Area after permission had been refused by the Minister for Defence’.

As an individual trying to get a close-up view of Pine Gap, Robert Cooksey was a nuisance but nothing more. Of much deeper concern for ASIO was the possibility that he was acting on behalf of (and perhaps being funded by) a radical political group.

While Cooksey and Ball had both taken part in organised political protests against the Vietnam War and against South Africa’s apartheid regime, Cooksey was not believed to be a member of the Communist Party. According to a declassified ASIO document he regarded himself as being ‘left wing ALP’ and had stated that he was ‘not a communist and would not entertain the thought of joining the Communist Party’ because of the ‘irrelevancy of Marxism to Australian conditions’.

During his brush with the police officer outside the boundary fence, Cooksey ‘did not mention his association with any organisation other than the ANU [and] “Age” newspaper . . . the opportunity did not occur . . . to glean any further information regarding Ball’s membership of any associations’.

In his letter to Sir Henry Bland, the ASIO chief described Ball as ‘an associate of students who have radical views’, while Cooksey had been ‘reported as having contact with Communist Party of Australia personalities’ and was ‘considered to be indiscreet’. Try as it might, ASIO could find no evidence that

either Cooksey or Ball was a member of the Communist Party.

Ball, however, would continue to be viewed with suspicion by senior officials in both defence and intelligence, who regarded his efforts to prise open the secrets of Pine Gap as tantamount to treason.

It was not only Arthur Tange and the heads of ASIO who distrusted Ball. Between 1975 and 1980 Milton Corley Wonus was the CIA station chief in Canberra. Wonus was an expert in signals intelligence, having worked as a US Air Force SIGINT analyst in Japan during the 1950s.

Unlike previous CIA station chiefs, Wonus had a background in the agency’s Directorate of Science and Technology, the division responsible for the design

and operations of the Rhyolite spy satellite program and the development of Pine Gap. The American was not an admirer of ASIO. According to Paul Dibb, Wonus felt that ASIO ‘viewed the Russians from the standpoint of the 1950s’, that it had a ‘blinkered view of Soviet operations in Australia’ and was still behaving like ‘the policeman on the beat’.

Whereas Wonus believed the Russians were playing a ‘sophisticated and subtle game, especially in . . . seeking political and other influence in high places’, ASIO was stuck in the past and spent its time ‘tailing the Russians on

their more obvious contacts with Australian communists’.

Dibb wrote that Wonus had ‘two pet hates’. One was the US spies Boyce and Lee, whom he ‘wanted to see . . . executed’. The other was Des Ball, who, in the American’s view, had ‘revealed dangerous information about US intelligence installations in Australia, especially Pine Gap’.

Fortunately for Ball, the CIA station chief expressed no desire for him to be terminated.

1 Pingback