Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost

On Oxford Street in Central Sydney, where I lived for some months while researching Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost, the homeless, were regularly moved on; rough sleepers driven from public view.

Drunks, wayward, schizophrenics, Sydney’s lost and troubled, those who heard voices and slept rough, had long washed up along a particular stretch or corridor of what was known as Oxford Street. The thoroughfare stretched for several kilometers from the formalities of Hyde Park and the War Memorial.

It passed up through Paddington, once a working class suburb and student lair whose terraces now sold for well over a million dollars each.

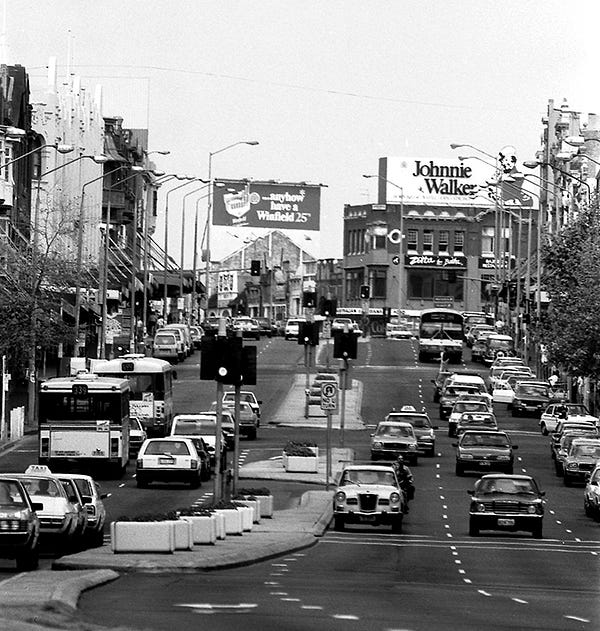

But when people referred to “Oxford Street”; they usually meant just the bottom of the stretch, a six lane road which sloped upwards from the park to an intersection known as Taylor Square. It was a strip of about one kilometer. On either side there was a motley dribble of small, shabby businesses, fast food outlets, restaurants, cafes, a few bars, a diminishing number of sex shops, and, in a sign of the times, numerous empty stores.

In decades gone by Taylor Square had been a busy but poorly lit, atmospheric square; a kind of alternative center of the city to the business district’s Martin Place.

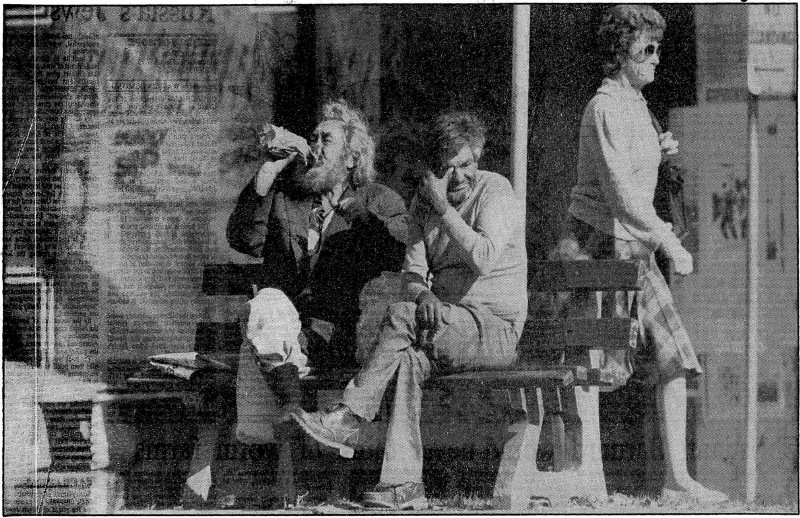

At its heart had been a mound of pounded earth colloquially known as Gilligan’s Island, where the city’s drunks instinctively gathered each day as if it was a sacred site.

Men in suits gathered at Martin Place, men in rags gathered at Gilligan’s Island.

The Glorious Smell of Fresh Ink

Way back then, in the 1980s, when he had been a news reporter for the city’s major newspaper The Sydney Morning Herald, Alex, an aging, distracted, sometimes dishevelled reporter bearing an uncanny resemblance to the author, had done a story on the last night of Taylor Square’s newspaper vendor.

The stand had been known throughout the city as the first place it was possible to get an Early Edition.

Job seekers, late-night workers, collectors competing for bargains amongst the classified ads, young journalists who, like his younger self had excitedly lined up to buy a copy of the paper so they could see what their stories looked like in the print, all had lined up to buy in those pregnant, possibility filled minutes before midnight.

Queues of taxis would form, waiting, waiting for that glorious smell of fresh ink.

There had been a lot of calls the next morning after that story: people who wanted to tell their own anecdotes about the newspaper vendor, how their whole lives had changed as a result of a purchase there; how they had been the first to answer an advertisement for a job in New Guinea, met their wife or lifetime partner there, now had grandchildren. Every caller had a story of their own.

The newspaper vendor, the coin filled aprons, the piles of first editions dumped fresh from the delivery trucks, had long since disappeared into the city’s history. As had Gilligan’s Island.

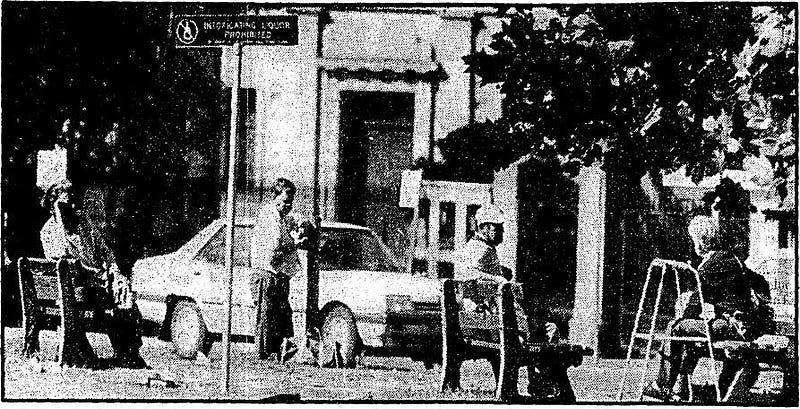

What was once such character crowded part of Sydney had long been vanquished by a corporate makeover; the dead hand of the modern day Sydney City Council everywhere.

A dreary “contemporary” water sculpture and a neatly grassed mound replaced Gilligan’s Island; and while ratbags and the just plain ratty still wandered from the nearby hostel for the homeless, Edgar Hoover Lodge and the neighboring Sydney City Mission, the transformation was more or less complete.

Along with the rest of the city, Taylor Square had been dragged into deathly shallows of the 21st Century, and was no better for it.

It may have been dying when he arrived, but in the six months that Alex lived at the bottom of the strip it turned up its feet and died.

When Alex had arrived for the Christmas of 2014, there had still been a few spasmodic signs of life: late night clubbers, suburban adventurers, cruising rat packs, groups of women out for a night, gangsters and aspiring gangsters aiming for one of the city’s only early morning drinking clubs. The club was soon to close. The suburban adventurers gave up all hope of finding entertainment.

The wanton lads of the gay demimonde stayed home and watched television.

Yet some signs of character still persisted. The area continued to attract the odd and the unformed, the fallen angels, those whose grasp on the terrain was very weak indeed.

Curiously, as if spilling down from a central source, a random, small and shifting cast of the homeless still kept trying to make their rudimentary camps along Oxford Street, usually a blanket on the pavement, perhaps a bag, those little nests that man had made since the beginning of the species.

They slept in the doorways of Oxford Street for a few days; and then disappeared.

In decades gone by their equally troubled forebears, gathering ritualistically each day, had found refuge, solace, drinking companions in these very same places, their madness seemingly less extreme in the company of others, a black humor all pervasive. Sting, a mixture of orange cordial and methylated spirits, could always be shared. There was always a hiding place somewhere, even on an open street.

Henry Lawson and the Streets of Darlinghurst

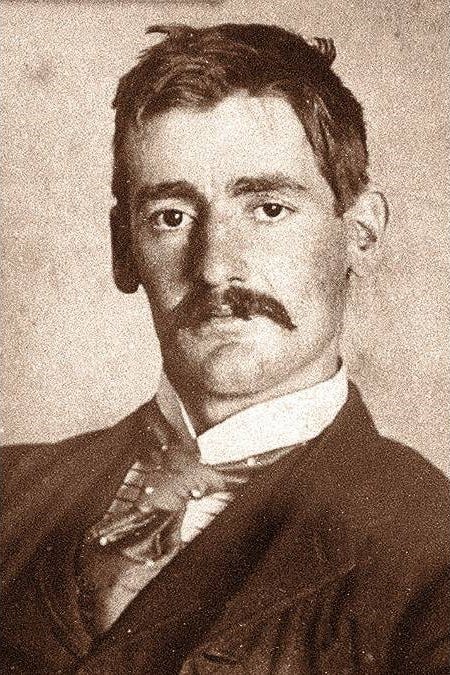

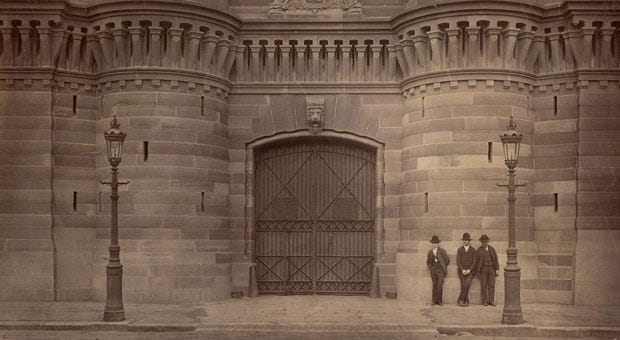

Just at the top of Oxford Street, next to Taylor Square, lies what was once Darlinghurst Jail, a place where one of Australia’s most intensely lyrical poets and greatest storytellers, Henry Lawson, was frequently incarcerated for drunkenness or vagrancy.

During Lawson’s time bridging, into the 20th Century, he had seen the area from high and low; as a nationally famous writer; and as a hapless, disregarded derelict.

The entire block was now an Art School.

Henry Lawson was one of those repeatedly attracted to the areas of Sydney’s inner-city demimonde, those exact same streets Alex often traversed, from Kings Cross to Taylor’s Square and many an alley in between. Alex often wondered as he walked those same streets what Henry Lawson would have made of Sydney in 21st Millennium, what he would have written.

Lawson may have been haunted by his own ghosts, but Sydney was now full of ghosts.

It was during his periodic dives into alcoholism that Lawson found himself drifting with the very same people that drifted on Oxford Street still; the lost and the deranged.

With some parts of Sydney now having 70% of their population born overseas, Australia’s new immigrants knew nothing of the country’s vagabond, literary past; while the new creatures of the bourgeoisie, cashed up from the property boom, would have dismissed Lawson in an instant as nothing but a drunken scumbag sleeping on the street.

They might admire his work at some literary festival or other, they would never have invited him into their homes.

But it was Lawson who would be remembered as one of Australia’s greatest writers, long after the miserable gits who had made his life hell were dead, buried and forgotten.

The poem he wrote from Darlinghurst Jail, One hundred and three, after the number he was given in prison, says it all:

A criminal face is rare in jail, where everything else is ripe —

It is higher up in the social scale that you will find the criminal type.

But the kindness of man to man is great when penned in a sandstone pen —

The public call us the ‘criminal class,’ but the warders call us ‘the men.’

The clever scoundrels are all outside, and the moneyless mugs in jail —

Men do twelve months for a mad wife’s lies or Life for a strumpet’s tale.

If the people knew what the warders know, and felt as the prisoners feel —

If the people knew, they would storm the jails as they stormed the old Bastille.

A century after the poem was written Australia’s social justice system was just as bad as the world Lawson knew; the society just as hypocritical, the nation’s oligarchies as contemptuous of the population from whom they plundered their fortunes, the laws, created to suit the rich and only the rich, as barbaric and ill informed.

Spiritual Harmonics and the Drift of Fallen Angels

While the homeless and the alcoholic were regularly moved on, the soulless grip of the authorities worse than ever, on Oxford Street the drift of fallen angels persisted.

It was as if something, some powerful comforting force, had once occupied the place when it had all been tribal lands.

As if, long before English brutality had paved the way for bitumen streets and Western jails, this place had drawn the wayward spirits of an ancient tribe, and now, in another century, there were residual compass affects; spiritual harmonics which had chimed down the centuries.

It came as no surprise to learn that Oxford Street, according to some historians, ran along the paths the Indigenous had walked for millenia.

Even though the bodies to which the old spirits had been attached had long since passed on, this place still attracted the disturbed, weather vane personalities of street people who appeared, for whatever reason, to find in the otherwise unremarkable strip of road a place which was the closest they could come to stability, mental or otherwise, in the chaos and often enough agony of their own collapsing life stories.

Unlike days of yore, the homeless were now an untidy inconvenience unbefitting the twee image the Sydney City Council wanted to portray and were inevitably moved on.

Despite all the local, state and federal rhetoric about the poor and the vulnerable in the community, the bleeding heart planks from which so many expansive, expensive and more often than not counterproductive bureaucracies had been built, there was no room in Sydney’s unfriendly heart for the soulful or the unsuccessful.

But whether anyone cared or not, these people still gathered in much the same places; exhibited their deranged behaviors for a few hours or a few days before an uncomprehending and uncaring audience; and waited for the authorities to hose them down and out, away from public view.

Off to rehab, off to homeless shelters, off to psych wards, off to some terrible, sober confrontation with their own worst selves.

MONEY$LENT

As the sun came up over Oxford Street early one summer morning a van of police pulled up for coffees outside the Swiss Bakerz Cafe, a couple of hundred meters down from Taylor Square.

Two men, two women, a gender balance only the elderly might think worthy of comment, disembarked from the police vehicle.

Sitting on the park bench with a man who was just out of jail and a few other assorted, the old journalist, whose adopted name for the purposes was Alex, took in the scene.

Next to the 7/11 was the bright yellow and black signage of a pawn shop: “MONEY$LENT”; parked out front a shopping trolley full of old clothes and makeshift bedding.

On the downhill side there was a dilapidated string of establishments catering to base instincts: The Den, VIP Lounge, Toolshed.

“This is Australia,” the old man said, apropos of nothing. Council workers swept the streets of the evening’s litter and by 8am the yellow flack jacketed parking patrols were already out, searching for that easiest of targets, a citizen looking for a parking spot.

The Sydney City Council made some $70 million out of parking meters and extortionate fines; and had no motive whatsoever to solve one of the problems which made Sydney such an unpleasant and expensive place to live, the absence of anywhere to park. On the sidewalk there was a not unusual sight: an over-excited man, his arms jerking, his eyes bulging, moving erratically in front of the early opening cafes and shops, shouting fragments of sense.

The country, disintegrating at the seams, was in the midst of an ice epidemic.

Another consequence of prohibition, of idiot laws by self-serving politicians always ready to whip up moral panic around law and order for the sake of a vote, was that the drug was being regularly cut or substituted with an even cheaper alternative known as “jump”; and much of the bug-eyed madness of the loosely integrated now a common feature of street scenes was due not to the drug itself but to the garbage with which it was being cut.

As they waited for their coffees from the Swiss Cafe and bought odd things from the neighboring 7/11, the police appeared to decide they might as well do some work at the same time, and pulled the over-excited man aside, one part Aboriginal, nine parts lost.

A minor assortment of that morning’s vagrants watched on as the police went about their “duty”.

They included a tribal man from the arid Pitjantjatjara Lands of Central Australia, one of the world’s most truly beautiful stretches of arid land.

Pissed for sure, but wreathed in a kind of elder statesman’s dignity, he was almost 3,000 kilometers from home.

On that bench, at the bottom of the ladder, drunk in the dawn, everybody was kind to each other, friendly in an unfriendly city.

The police donned the demeaning occupational health and safety rubber gloves which had become standard for body searches since the Grim Reaper fears of AIDS and needles.

The gloves gave the distinct impression the authorities were afraid of being contaminated by the poor; that they weren’t dealing with fellow humans but with some diseased, leprous underclass.

The police made the man spread his legs, turn around and put his arms up against the shop front.

It was a humiliating stance, but the police, friendly enough in a place which sooner or later saw more than enough of the comic, cosmic and bizarre, also combed through his possessions, a carry bag of dirty clothes, the sandshoes he had kicked off.

It was ridiculous

If the man had anything significant to hide beyond personality problems it was unlikely he would have been wandering the street in such a deranged state.

With their search finding nothing the police told him to wait while they checked if he had any “outstandings,” warrants from the past that might justify taking him into custody.

The man, already upset at being frisked on a public street, wasn’t going to stand for any of that, and headed off down the street without shoes, making odd shouts, weaving wildly.

The police made as if to follow him, but then just watched as he disappeared down Oxford Street, in between the mixing shifts of people heading home or people heading to work; the office workers replacing the night denizens.

Nothing the police could do was going to make any difference.

The news came through, there were no outstanding warrants, making the man of even less interest.

His shoes and his bag, his haphazard collection which barely classified as “belongings,” remained in a small pile by the shop front. As they climbed back into their vehicle, the police packed them neatly next to the garbage bin.

A man who had almost nothing now genuinely had nothing.

Soon enough the over-excited man would be someone else’s problem. Almost inevitably he would be jailed again for some minor infraction; re-incarcerated into a prison system which, thanks to mistaken policies of the past, was overloaded with the mentally ill.

Wealth, mental stability, sobriety, a stable temperament, a loving and preferably powerful family, a lack of the alcoholic gene, a lifetime of achievement and high social status, they all bought protection from the harassment of authorities.

On the other hand street alcoholics had always been easy prey.

Fleeing harassment, or fearing incarceration, the wild-eyed man gave a final jag at the bottom of the street and disappeared into the early morning traffic.

Adapted from the book Terror in Australia: Workers’ Paradise Lost.

John Stapleton worked as a journalist on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.