To mark the 50th anniversary of the Australian Family Law Act in 2025 A Sense of Place Magazine is running this series Classics of the Fatherhood Movement.

Also, keep an eye out for the upcoming book from A Sense of Place Publishing, Failure: Family Law Reform Australia by veteran journalist John Stapleton.

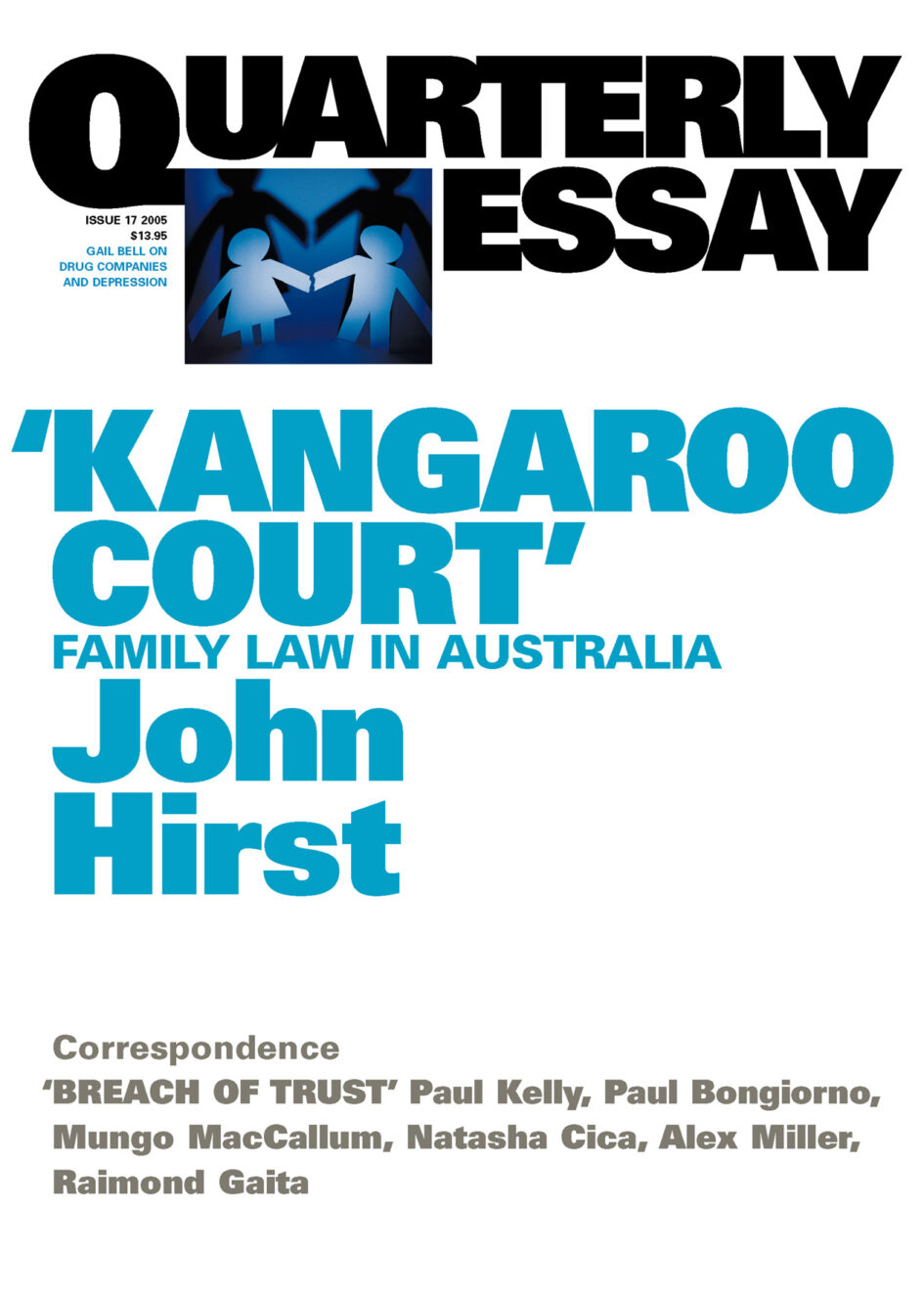

John Hirst’s long form essay Kangaroo Court is an incisive critique of the Australian Family Court, analysing its operations, the social impact it has had, and the broader implications for justice and family law. Hirst argues that what began as a progressive reform in the 1970s has turned into one of Australia’s most hated institutions.

John Hirst was one of Australia’s greatest historians. His books included Freedom on the Fatal Shore, The Sentimental Nation and Sense and Nonsense in Australian History. He also edited the seminal collection of essays from some of the nation’s foremost writers, The Australians.

The book delves into the court’s practices, particularly its intense focus on the “best interests of the child,” which Hirst suggests has led to a system where justice can be skewed, and allegations often go unchecked. He highlights the court’s significant power over individual lives, questioning its self-description as a ‘caring court’ against the backdrop of widespread public discontent.

When Family Court judges talk piously of the ‘caring court’, I wish they could hear the roar of pain that their piety has caused.

JOHN HIRST

I cannot see the way by which the Court can be rescued. Until there is fundamental change, it will continue to give offence.

- The Australian: “John Hirst’s ‘Kangaroo Court’ is a devastating critique of the Family Court, marrying legal analysis with poignant personal narratives. His call for reform is both urgent and compelling, making this book essential reading for anyone concerned with justice in family law.”

- Sydney Morning Herald: “‘Kangaroo Court’ offers a sharp, unapologetic look at the dark underbelly of family law in Australia. Hirst’s rigorous examination challenges readers to reconsider how justice is administered in one of society’s most emotionally charged arenas. His work is not just academic; it’s a clarion call for change.”

For an academic historian working out of La Trobe University was unusual in that he was more than happy to confront the left wing orthodoxies of the day, particularly when it came to family law. It was an extremely refreshing change when the controversy family law has been so utterly distorted by academics who have studiously ignored the outcry from the general public.

Kangaroo Court does not shy away from controversy, offering a perspective that many find resonates with their experiences or observations of the Family Court system. By dissecting specific cases and legal principles, Hirst challenges the reader to think critically about what justice in family law should look like and how it might be reformed to serve better those entangled in its processes.

He explores the Court’s fervour to uphold the best interests of the child no matter what and traces its chilling consequence- a court where malicious allegations regularly go unpunished. He notes the Court’s enormous power over individual lives, as well as its self-proclaimed status as a ‘caring court’, and wonders at its ability to overlook the defiance of its own authority. In closing, he considers how to reform an institution that has bred antagonism and extremism and too often entrenched paranoia and despair. Lucid and urgent, ‘Kangaroo Court’ is a cautionary tale about the perils of high-mindedness when it comes to dealing with the breakdown of families.

It’s hard to believe, as we head into 2025, that Australia’s Family Law Act, the most impactful and destructive legislation to ever pass the parliament, began with such apparent optimism and goodwill.

Here is a short extract from Kangaroo Court:

The Family Law Act of 1975 which established the Court was a progressive social reform of the Whitlam Labor government. It was not an exclusively government measure; members on both sides were allowed a free vote and Liberals had been among those working for divorce law reform. The Act removed fault as a ground for divorce and replaced it with irretrievable breakdown, to be indicated by a one-year separation. The aim was to allow couples to part without the trauma and contrivance of one partner proving fault against the other. Marriages would be buried decently and humanely. The business of dividing property, arranging maintenance and determining custody of children would remain, but these were to be settled in a simple, flexible and inexpensive way. Litigation was to be discouraged and the Court was to be staffed by social workers and counselors as well as judges. It was to be a court of an entirely new sort, a “caring court” or a “helping court”.

If proceedings were to be simple, flexible and cheap, why, say the wits, were lawyers put in charge of them? Proceedings quickly became complex, rule-bound and expensive.

A caring court in the hands of lawyers? What were they thinking?

CLASSICS OF THE FATHERHOOD MOVEMENT

CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW TO SEE THE SERIES SO FAR

OUT SOON

MARKING THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE AUSTRALIAN FAMILY LAW ACT

2 Pingbacks