Tim Nelson and Joel Gilmore, Griffith University.

Australia is in the grips of an energy crisis, with electricity generation prices roughly 115% above the previous highest average wholesale price ever recorded.

The price for electricity in New South Wales for this quarter (March to June), for instance, is currently at a staggering A$300 per megawatt hour.

Future electricity prices are also increasing to previously unimaginable levels. The market is pricing electricity contracts for next financial year at $238 per megawatt hour – around 180% higher than what it traded at the beginning of this year.

The Labor government has ruled out triggering an emergency mechanism to restrict gas exports, a mechanism many say would help ease household prices. In any case, we propose three additional ways it can start to ease the pressure on prices.

Wait, what’s going on?

The Australian Energy Regulator recently approved household electricity price rises of up to 20%. The regulator noted prices are increasing due to a jump in wholesale prices (which we predicted back in March).

Wholesale prices are the price of generating electricity and have historically represented around 35% of the final bill for households. There are three key drivers of wholesale prices:

- the cost of building new generation: if capital costs and financing costs for new projects increase, then wholesale prices are also likely to increase

- supply and demand: how much generation is available relative to demand

- the cost of operating existing generation: if input costs, such as coal and gas prices, increase then electricity prices are also likely to increase.

Contrary to much of the existing commentary, it is a combination of the second and third drivers that has resulted in prices increasing to unprecedented levels.

First, let’s look at input costs. The price of coal and gas has surged as a consequence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Due to formal sanctions and informal shunning of Russian exports, thermal coal prices have increased five-fold to an unprecedented $A500 per tonne. This has increased the cost of energy from coal-fired generation to over $150 per megawatt hour.

Gas prices have also increased substantially as a consequence of sanctions against Russia. Prices jumped from $6-12 per gigajoule in the first three months of 2022, to around $50 per gigajoule at the end of May.

They’ve been so high that governments and regulators have intervened and capped prices at $40 per gigajoule. This means electricity generation from gas has increased in cost to around $300 per megawatt hour.

But the second – and less spoken about – impact is the significant reduction in supply of generation during April, May and now June.

Many coal power stations were partially or totally taken offline in April. We saw a step change in pricing overnight on April 1, when prices changed from around $100 per megawatt hour in March to around $200 per megawatt hour in April.

Whether offline for maintenance or to maximise generator profits, it’s not clear why so many coal generation units have not been available to generate.

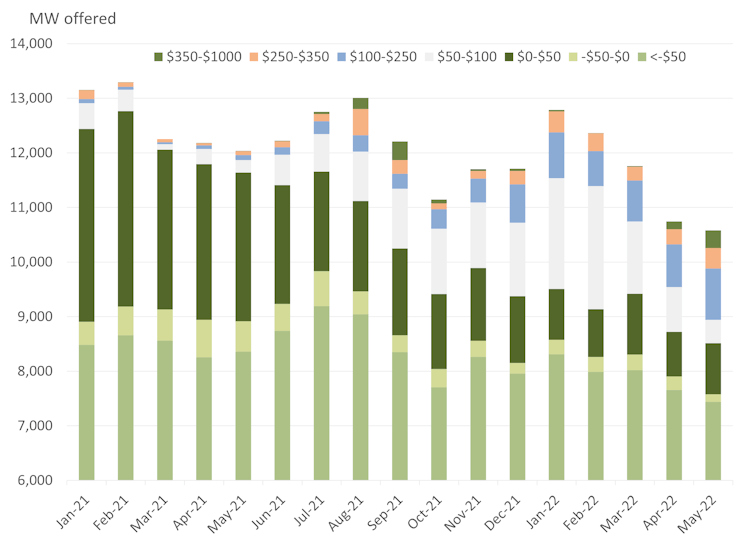

The chart below (sourced from Australian Energy Market Operator operational data) shows the total black coal generation offered at various prices in April and May is materially lower than the previous 18 months (and, in particular, relative to the previous April and May).

The fact so many coal units have been unavailable has led to a significant increase in gas-fired generation to fill the gaps, despite it being so expensive to run.

As such, the generator setting the price in the wholesale electricity market during April, May and now June was almost always a gas-fired plant, resulting in prices rising to such unprecedented levels.

How should Australia deal with these horror prices?

1. An inquiry into why so many coal plants weren’t available

At the very least it would seem prudent to task the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission with an inquiry into why so much coal generated power has been unavailable during April, May and June.

If it is for maintenance purposes, it will be important to learn how better to schedule this to ensure similar outcomes don’t occur in the future.

An inquiry will also be able to determine if a coal plant has been unavailable due to market power driving prices higher. To be clear, the problem is not with removing coal over time – just that in this case, the shortage of capacity was unexpected.

2. Turbocharge renewable energy efforts

The new government should accelerate investment in new electricity supply by increasing the legislated renewable energy target, which has delivered 20% renewable energy, but can be increased substantially to reduce our exposure to high fuel costs.

This should also involve amalgamating emerging state-based initiatives, such as the New South Wales government’s 12 gigawatt energy roadmap, making it easier for investors to coordinate across different states.

An updated national target could also create room for emerging projects, such as offshore wind, to accelerate their development.

A stronger renewable energy target will increase electricity supply, and place downward pressure on prices.

3. Implement a capacity reserve

The new government should work with the Energy Security Board to implement a reserve mechanism for new “dispatchable” capacity – such as batteries, pumped hydro, hydrogen-ready turbines – to drive investment and ensure they’re in place before coal is phased out.

This is much more efficient than recent proposals for a capacity mechanism suggested by coal-fired power station owners to pay existing coal generators for their capacity. It’s clear from the current situation that Australia’s ageing coal plants cannot be relied upon.

We all need to remember electricity is an essential service. Acting quickly is crucial to avoid households falling into hardship, and businesses closing their doors.

Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University and Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.