By Gareth Wearne, Australian Catholic University

On Tuesday news broke of the discovery of fresh fragments of a nearly 2,000-year-old scroll in Israel. The fragments were said to come from the evocatively named Cave of Horror, near the western shore of the Dead Sea.

The finds were announced with attention-grabbing headlines that these were new fragments of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls and some of our earliest evidence for the biblical books of Zechariah and Nahum.

But more than just remnants of ancient text, the discovery reflects the troubled history of the Dead Sea Scrolls and tells human stories of revolution, a desperate search for safety and archaeological ingenuity.

Read more: Dead Sea Scrolls: how we accidentally discovered missing text – in Manchester

People of the scroll

Information is still coming out, but unusually for ancient discoveries of this kind, we know something about the people who hid the scroll.

The Cave of Horror is one of a series of eight caves in the canyon of Naḥal Ḥever, which were used as places of refuge during a Jewish revolt against Rome (132–135 CE)in the time of the emperor Hadrian. The revolt was led by Simon bar Kochba (or Simon bar Kosebah, as he is also known in ancient sources), who was thought by his followers to be the Messiah.

The cave has been known to archaeologists since 1953, but it wasn’t until 1961 that it was excavated by a team led by the Israeli archaeologist, Yohanan Aharoni. The new fragments were found as part of a larger project to search for new manuscripts, which is being conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The cave is remote and difficult to access, which is doubtless why it was used as a hiding place. Aharoni describes the entrance as being 80 meters below the edge of the canyon with a drop of hundreds of meters below it. The team who first explored the cave in 1955 had to use a 100-meter-long rope ladder to reach the opening.

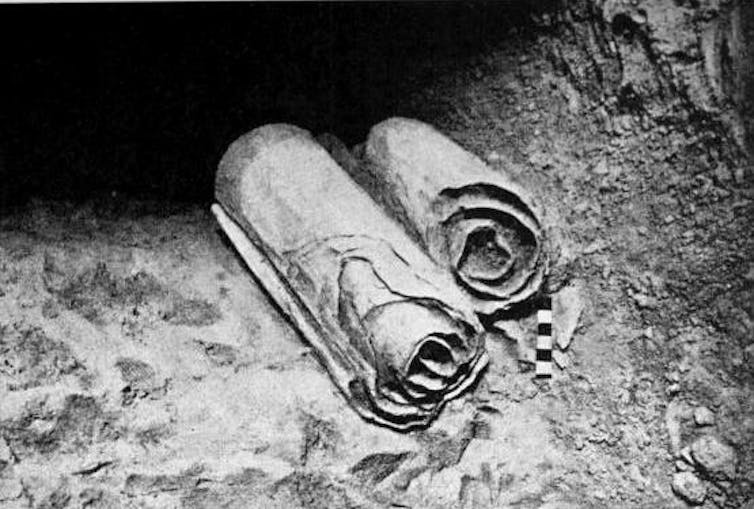

The nickname Cave of Horror was given to the cave because of a large number of skeletons, including children’s skeletons, that were found inside. Together with the skeletons were personal documents, a fragmentary copy of a prayer written in Hebrew, and the scroll to which these fragments belong, which was hidden at the back of the cave.

Remains of a Roman camp at the top of the cliff suggests the refugees sheltering there died as a result of a Roman siege. The occupants were determined not to surrender. There were no signs of wounds on the skeletons, suggesting the occupants died as a result of hunger and thirst, or possibly smoke inhalation from a fire in the centre of the cave.

They buried their most prized possessions, including the scroll from which these fragments come, to keep them safe.

Our oldest biblical texts

The photographs and reports released by the IAA indicate the fragments contain our earliest copy of Zechariah 8:16–17 and one of our earliest copies of Nahum 1:5–6. The fragments appear to be missing pieces of a scroll already known to scholars — the Greek Minor Prophets scroll from Naḥal Ḥever, or 8ḤevXIIgr to give it its official designation.

As the name suggests, the scroll is a copy of the Greek translation of the biblical minor prophets, containing portions of the books of Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, and Zechariah. The “minor prophets” or “the twelve” customarily describes the books spanning from Hosea to Malachi in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament.

Among other things, the minor prophets include the story of Jonah being swallowed by a “great fish”.

Read more: The Dead Sea Scrolls are a priceless link to the Bible’s past

Don’t say His name

The ancient Hebrew scriptures were first translated into Greek for the benefit of Greek-speaking Jews who had begun to lose contact with their Hebrew roots. Ancient sources, such as the letter of Aristeas, indicate the work of translating the scriptures into Greek probably began in Egypt, some time around 200 years before Christ.

A fascinating feature of the Greek Minor Prophets scroll is the fact the name of God is written in Hebrew, not Greek. This practice stems back to the prohibition in Exodus 20:7 against “taking God’s name in vain”.

The Dead Sea Scrolls attest several practices for avoiding accidentally pronouncing the divine name while reading aloud. These include substituting dots in place of the letters and the use of an archaic form of the Hebrew alphabet.

This custom is the basis for the modern practice of writing Lord in capital letters in modern editions of the Bible.

Beating the looters

Shortly after the discovery of the first Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 it became apparent the rare ancient manuscripts had financial value. This led to a race between archaeologists and local Bedouin to discover more scroll fragments.

Consequently, it can be difficult to verify the archaeological provenance of many of the Dead Sea Scrolls remnants.

More recently, fake scrolls have found their way into at least one modern museum collection. A new manuscript discovery with secure archaeological provenance, like the one announced last week, is immensely important.

Perhaps most excitingly, these new fragments leave open the tantalising possibility there are more scrolls out there, waiting to be found.

Read more: Fake scrolls at the Museum of the Bible

Gareth Wearne, Lecturer in Biblical Studies, School of Theology, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Originally published 23 March, 2021.